I suspect you normally don’t read Bee Culture for existential ponderings, but before you skip over this article for more practical beekeeping advice, I want you to think, right now, what you would do if you just found eleven colonies dead in your beeyard? I can tell you what I would do: I would shake out the bee corpses, stack up the dead hives on the back of my truck, de-glove in the cab and then stiff arm the steering wheel, causing the horn to emit a long existential honk. Maybe you would act more gracefully and skip the horn honking, but I bet you would still find that existential question creeping into your head—what is all this beekeeping stuff for? It’s a question I’ve asked myself many times over the years.

Beekeeping is not for the faint of heart—or faint of mind either. A beekeeper who is “keeping bees to help save the bees” is a beekeeper who has yet to wrestle with the harsh reality that most beginning beekeepers will kill more bees than they will ever help save. The beekeepers who reload and return to the beeyard, despite the despair of dead outs, may eventually tilt their cosmic scales back toward bee savior, but, on average, I wonder how many hives die before a beginning beekeeper actually becomes proficient enough to save bees—that is to keep bees from drowning under the virus load of varroa. It probably took me thirty dead outs over five years before something finally clicked and I started overwintering hives successfully and my hive numbers started multiplying.

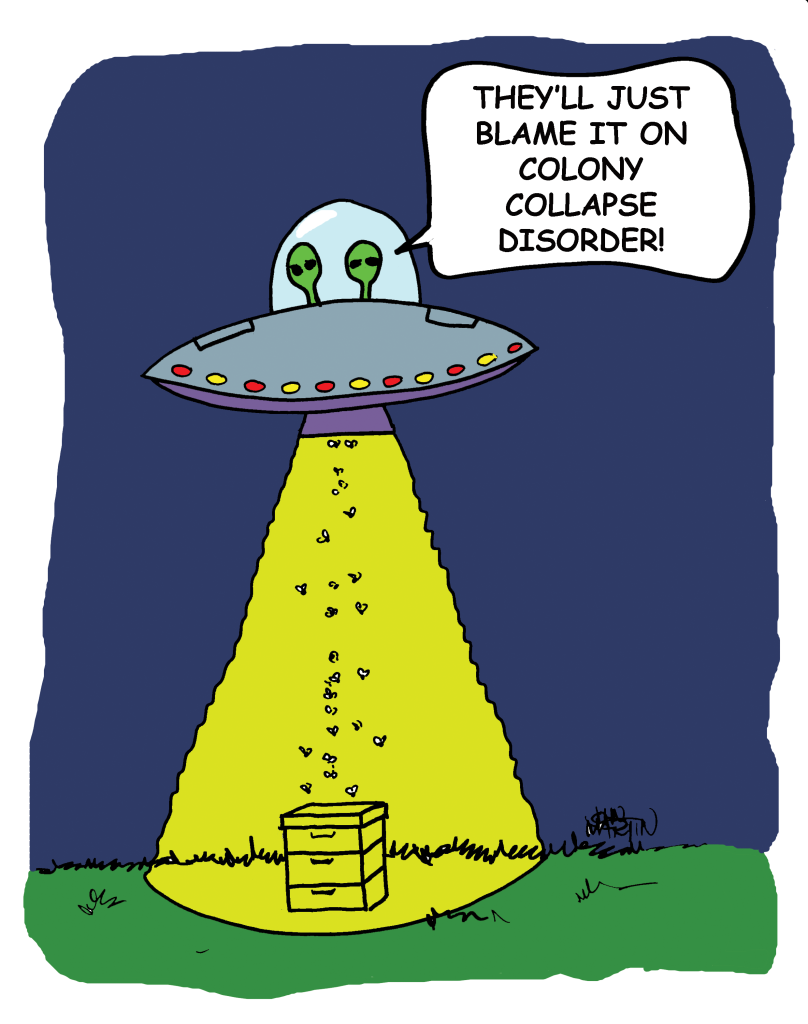

Now, I’m in my tenth year of beekeeping, at least if you count the first five years which were mostly me killing bees. Sure, I could say it was varroa that killed them or pesticides or small hive beetles or poor nutrition or extraterrestrial bee snatchers or whatever the excuse de vogue at the time was (at the time, I think I just lumped all these excuses into a singular catch-all excuse called Colony Collapse Disorder). But the truth is my hives died because, first and foremost, I didn’t listen. I didn’t listen to the advice of seasoned beekeepers because I thought I knew more than they did. I didn’t listen until, finally, enough cognitive dissonance erupted between my bee savior desire and my bee killer despair that I finally asked the great existential beekeeping question—“To beekeep, or not to beekeep?”

I chose to beekeep and not beekill—that is, to get serious about beekeeping, which is really the only way to keep bees now.

In fact, to be honest, I think the term hobby beekeeping is an oxymoron. Think about it this way: suppose you took up some other hobby for pleasure and relaxation. Let’s say fishing. You could just dig a few worms, buy a cheap Zebco and basic tackle, and then go catch bream or sunfish to your heart’s delight. And if by chance you didn’t catch any, well, a bad day’s fishing is still better than a good day’s work.

To fish, you don’t have to buy high-priced fishing gear, subscribe to Field and Stream, and join BassResource, the most popular bass fishing forum on the web. Of course, you could and many fishermen do. But even if you did—and this is the point—you still wouldn’t have to build your own farm pond and become an expert in farm pond management and ichthyological parasites to keep your bass from going belly up every Winter.

I say that in jest, but I would now like to say something serious to any aspiring hobby beekeepers who may be reading this. What follows is basically all the beekeeping wisdom I’ve learned in ten years distilled in one paragraph. It’s what I wished I would have listened to ten years ago when I first started. So, drum roll please, here goes my attempt to write something serious for once:

If you’re seriously trying to beekeep, the next three months are incredibly important. Usually beekeepers (myself included) get really excited about bees in the Spring. As Spring progresses toward Summer, some of that excitement fades because, let’s face it, working hives is hard work. Harvesting honey during the dog days of Summer is even harder work. Once your honey is in jars or buckets or barrels, you feel like you’ve accomplished your goal and take a well-deserved rest. Wrong. At least here in NC, mid- to late Summer is the most crucial time in beekeeping. Often there is a severe Summer dearth of nectar and pollen. Couple this with exploding varroa levels, and you’ve got a recipe for a dwindling hive. So, by the time October rolls around, you may only have a few frames of sickly bees, which is not what you want going into Winter. Though that hive will likely die during a February arctic freeze, it was really lost in those late Summer months.

So my advice is this: steel yourself for the upcoming dog days of Summer and invest in a bee jacket with good wicking technology. If needed, treat for mites and feed your bees. Taking good care of your bees is a lot cheaper than buying new bees each year—or talking to a psychologist because of existential beekeeping despair.

Stephen Bishop writes humor and keeps bees in Shelby, NC. You can follow his blog at misfitfarmer.com or follow him on Twitter @themisfitfarmer