Click Here if you listened. We’d love to know what you think. There is even a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

Becky Masterman earned a PhD in entomology at the University of Minnesota and is currently a host for the Beekeeping Today Podcast. Bridget Mendel joined the Bee Squad in 2013 and led the program from 2020 to 2023. Bridget holds a B.A. from Northwestern University and an M.F.A. from the University of Minnesota. Photos of Becky (left) and Bridget (right) looking for their respective hives. If you would like to contact the authors about your divides, please send an email to mindingyourbeesandcues@gmail.com.

Minding Your Bees and Cues

How to Bribe a Honey Bee

By: Becky Masterman & Bridget Mendel

About 100 million years ago, plants had a Lightbulb Moment – or more like Era. They were like, what if we bribed bees to pollinate us? So they began a marketing campaign on par with Shen Yun, complete with gaudy costumes and ornately color palettes, and the marketing ploy was basically, if you get into my flower, I will give you delicious candy. But also, I need you to run some reproductive errands.

Buttercups flashed yellow, magnolias showed off wedding-gown-themed petals and waterlilies opened up offshore operations complete with brutally gold coronas surrounded by layers of pink and white so deeply beautiful that they would one day become a symbol of rebirth for some humans, a species who were known for their inability to cooperate with each other or agree on anything.

So the plants noticed that bees were highly susceptible to advertising, and not only that, they would go to great lengths to get what they wanted, even evolving specialized features and skills such as long tongues, in response to new floral trends, such as tubular. They would basically do anything to get more nectar and pollen.

Of course, honey bees’ appetite for sweets exceeds other api-tites. This is partly because humans, known for being fixated on genetics even before genetics was a thing, spent about nine thousand years breeding bees to produce ever more honey, which they could then harvest to put on their toast. Despite this laudable work, they omitted thinking about how bees would even get the nectar to make the honey to soak the bread if landscapes were trashed to the point where they became inhospitable to flowers.

So — and we are absolutely not being bribed — we want you to help the flowers succeed. And yes, it’s a redundant request and we’ve written to you about this before, but now with fresh antics to lure you down the nectaries of our article, into our specially curated shortlist of easy to grow plants that will help YOU bribe your bees for honey.

Sunflowers: sunflowers are funny and joyful, and after feeding your bees, they will feed your birds in the Fall.

Dandelions: you don’t even have to plant them, and your bees adore them!

Clover: add white clover to your lawn to turn it into a delicious edible carpet for bees.

Apple trees: have you ever been under a flowering apple tree shaking with bees?

Joe Pye weed: Joe Pye is fun because it’s taller than us with big, sweet-smelling clusters of nectar-y flowers.

Mountain Mint! Not just any mint, mountain mint. Honey bees go insane for stands of it bursting with purple-flecked white flowers.

Calendula: These sticky-stemmed orange suns are beloved by bees, and keep blooming all Summer, especially if you deadhead often. And you can eat them too!

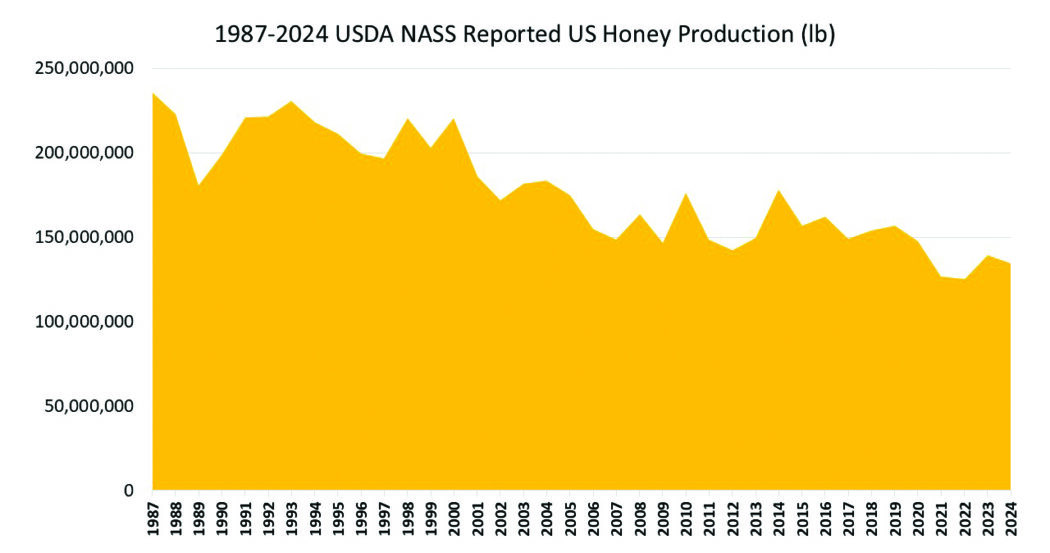

Figure 1. Shows the trend of U.S. honey production (lb) from 1987-2024. You will see honey production (lb) on the x-axis and the year reported on the y-axis.

Bachelor buttons: deep blue with nectar filled hearts, these flowers can grow in gardens or, if you have plenty of land, in fields. Bees adore them!

Tulsi Basil: grow a few pots of Tulsi basil on your front steps, so your bees will come visit you while you drink your morning coffee in the sun. This basil has darling little purple flowers and fire-orange pollen.

Buckwheat: quick to grow and abundantly blooming, buckwheat has delightful, delicate flowers that belies the deep dark honey it produces.

Opium Poppies: the big, open poppy flowers are like public pools for bees. We love watching all shapes and sizes of bees enjoying themselves together in the cup of a single bloom.

Borage: we are susceptible to borage’s blue eyed charms and your bees will be too!

Sedum: another Fall bloomer, this funny looking plant is findable at any garden store or hardware store, and great fast-food for bees.

Asters: purple! pink! white! Asters bloom late and long into the crisp days of Fall, when many other honey bee flowers have finished blooming.

Goldenrod: golden is also a late-bloomer and if you have plenty within foraging distance of your apiary, it’s a nice last chance for colonies who’ve been slow to build up their Winter stores…

Coda:

Beekeepers have been reporting their honey and bee data to the USDA since the late 1930’s. You can access (we think that you should!) and search honey production trends in your own state (https://www.nass.usda.gov/Quick_Stats/). It would be a great show and tell for your next bee meeting. When we see these graphs, we see vast tracts of wildflowers, fields of alfalfa, hedges of raspberry and goldenrod disappearing.

Scientists have also accessed these data for sweet (or not so sweet) insights into U.S. honey production trends. Page et al. (1987) analyzed yield data from 1939-1981 to propose the use of honey yield trends to analyze damage to the beekeeping industry. They reported that linear trends in honey yield per colony show that yields have increased in 29 states and decreased in 19 from 1939-1981. A more recent study by Quinlan et al. (2023) reported that honey yields across the United States decreased appreciably since the 1990s. They pointed to shifts in climate, land-use and large-scale pesticide application for decreased honey yields.

Figure 2. Shows the trend of U.S. honey yield (lb/colony) from 1987-2024. You will see honey yield (lb/colony) on the x-axis and the year reported on the y-axis.

References

Robert E. Page, Eric R. Nash, Eric H. Erickson (1987) Use of Honey Yield Data to Assess Damage to the Beekeeping Industry of the United States, Bulletin of the Entomological Society of America, Volume 33, Issue 3, Fall 1987, Pages 190–194, https://doi.org/10.1093/besa/33.3.190

Quinlan, G. M., Miller, D. A. W., & Grozinger, C. M. (2023). Examining spatial and temporal drivers of pollinator nutritional resources: evidence from five decades of honey bee colony productivity data. Environmental Research Letters, 18(11), 114018-. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/acff0c