Click Here if you watched/listened. We’d love to know what you think. There is even a spot for feedback!

Escaping the Virion?

By: Tracy Farone

As we trod through the end of Winter season into March, we see hopes of Spring in the occasional warm day, allowing us to get outside and get some fresh air. We look forward to getting back into our bees, shedding some layers and leaving behind the cold and flu season. However, much like us and our other animals, honey bees are plagued with dozens of different viruses. Have you ever wondered how viruses work… but have been intimidated by too much crazy science? This Spring semester, I have the privilege of teaching a public health and infectious course to my pre-health students. We learn that whether bee or bovine, human or hog, viral infections often follow similar, long-understood principles. Please allow me to put on the professor hat for a bit, bring you along for a lecture, and see how all this can be applied to our bees.

What Are Viruses?

A virus (virion, an infectious virus) is simply a bag of protein that contains one of the two nucleic acids, RNA or DNA. These nucleic acids carry or decode genetic code instructions to make all the proteins in our body parts that design us as we are and how we function. Virions infect cells by incorporating their own nucleic acids into the host cell to do the virion’s bidding.

There is still some controversy about whether a virus is a living thing or not, but no one disputes their ability to affect living things, sometimes severely. Viruses use cells to reproduce more viruses or hide out in cells, sometimes for years. Viral infection of cells can weaken or destroy cells and even stimulate our immune cells to attack and kill our own infected cells. Only viruses that are able to penetrate certain species of cells (human, dog, bee, bird) can cause infection in those species. Some viruses are able to only infect one species of animal, some develop the ability to infect many species. Virions capable of infecting animals and people are zoonotic viruses. Luckily, there are no zoonotic honey bee viruses, yet.

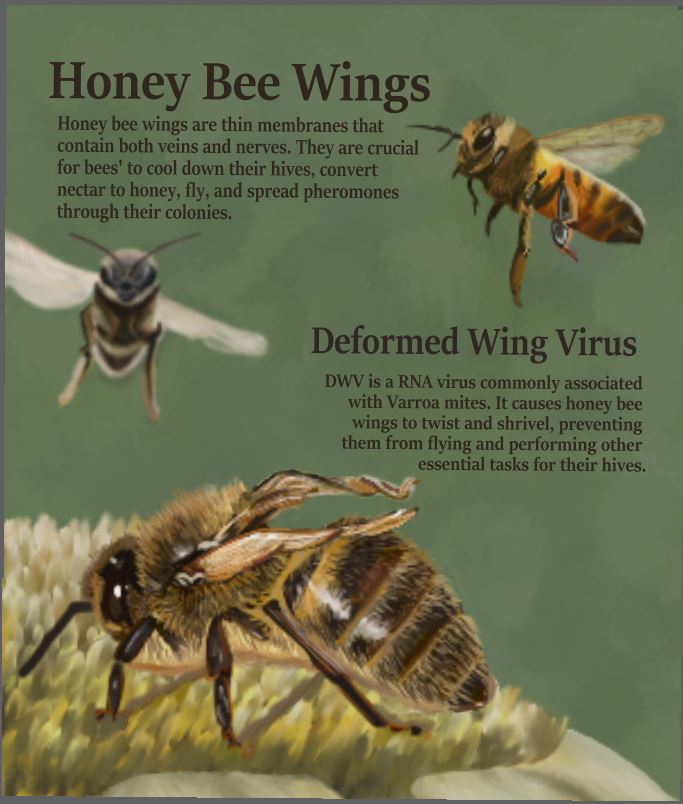

Because viruses are often passed from cell to cell and animal to animal there is a lot of potential for mixing and realignment of nucleic acids which results in different variants. This is why we see different influenza and coronaviruses emerging every year, and why, in honey bee viruses, we have discovered multiple variants in, for example, deformed wing virus (DWV), which now classify as variants A, B and C.

Basic Epi and Stats

When considering “data” and “facts” provided by any study or publication, it is helpful to have a basic knowledge of statistics and clear definitions of common terminology used. The study of how diseases work is epidemiology (epi).

First, there are four especially important things to understand about viral diseases:

- Sorry germophobes, but we may be exposed, covered and may contain trillions of viruses. Every day. It is a part of life on planet Earth. Coronaviruses (including SARS-CoV 2), Rhinoviruses, influenza viruses, etc. are all virions circulating in humans (and some animal populations). Honey bees also have dozens of viruses circulating in their populations and the more we look, the more we find.

- Most infections are subclinical infections. That means while the individual may carry the virus for a time, they do not show clinical signs and are not “sick.” Healthy individuals typically clear or “live with” virions with little negative effects. This is also true of most honey bee viruses.

- While new viral infections coming into a population may cause a temporary epidemic (new, high number of clinical cases), viral infections naturally break against the “herd” immunity wall of a general good health population and become endemic (low, expected number of cases) in a matter of months. This inevitability is good news for most.

- Viral infections most severely affect individuals of a population who are immunocompromised, those that are very young, old, have other diseases (co-morbidities), or have poor nutrition. These groups are more likely to be ill and to die in association with the viral infection. This concept is also the key to honey bee mortality involving viruses.

- Here are a few more terms to learn to evaluate.

The prevalence of a disease is the total number of cases of a disease in a population (group of animals/people) at a snapshot in time.

Incidence is the rate of new cases over a specified period (usually a year) within a population.

The number of clinical cases within a population is associated with a morbidity rate, which is the total percentage of sick individuals per total number in the population. So, if 121 million people in the U.S. get sick with rhinovirus (the most common cause of the common cold, coronaviruses are number 2) and if the population of the US is 346 million, the morbidity rate of rhinovirus would be 35% (121M/346M x 100).

The number of deaths per population is expressed as a mortality rate. Every disease is going to have some mortality. Influenza viruses on average kills between 20-51 thousand people “typically” each year in the U.S., most are elderly and/or immunocompromised (1). But obviously, we like to keep these rates as low as possible, typically a fraction of 1%. Mortality rates higher than 1% are concerning and rates higher than 10% are very alarming. COVID-19 adjusted mortality rates are now showing between 0.02-0.15% mortality rate over the entire “pandemic”, with the vast majority of the deaths occurring in elderly, comorbid, and/or immunocompromised patients (2). For comparison, Ebola virus’ average mortality rate is averages around 50%, rabies virus is almost 100%.

Bee Viral Data

While there is still much to learn and understand about honey bee viruses, we certainly know much more now than we did ten years ago. We certainly know that viruses are in our colonies. I have provided several articles below for those that would like to read more in-depth on the subject and a few links to some epidemiological data that we have on the prevalence of selected honey bee viruses. The USDA-APHIS data is user friendly and interesting to view. While the sample sizes are relatively small, the data does give a yearly overview of the U.S. viral prevalence of 10 different viruses. Deformed Wing Virus A and/or B variants are found in the majority of samples, up to 100% (3). However, this does not mean that every colony was ill with the virus but does indicate that the virus is widespread, likely well before the analysis was begun.

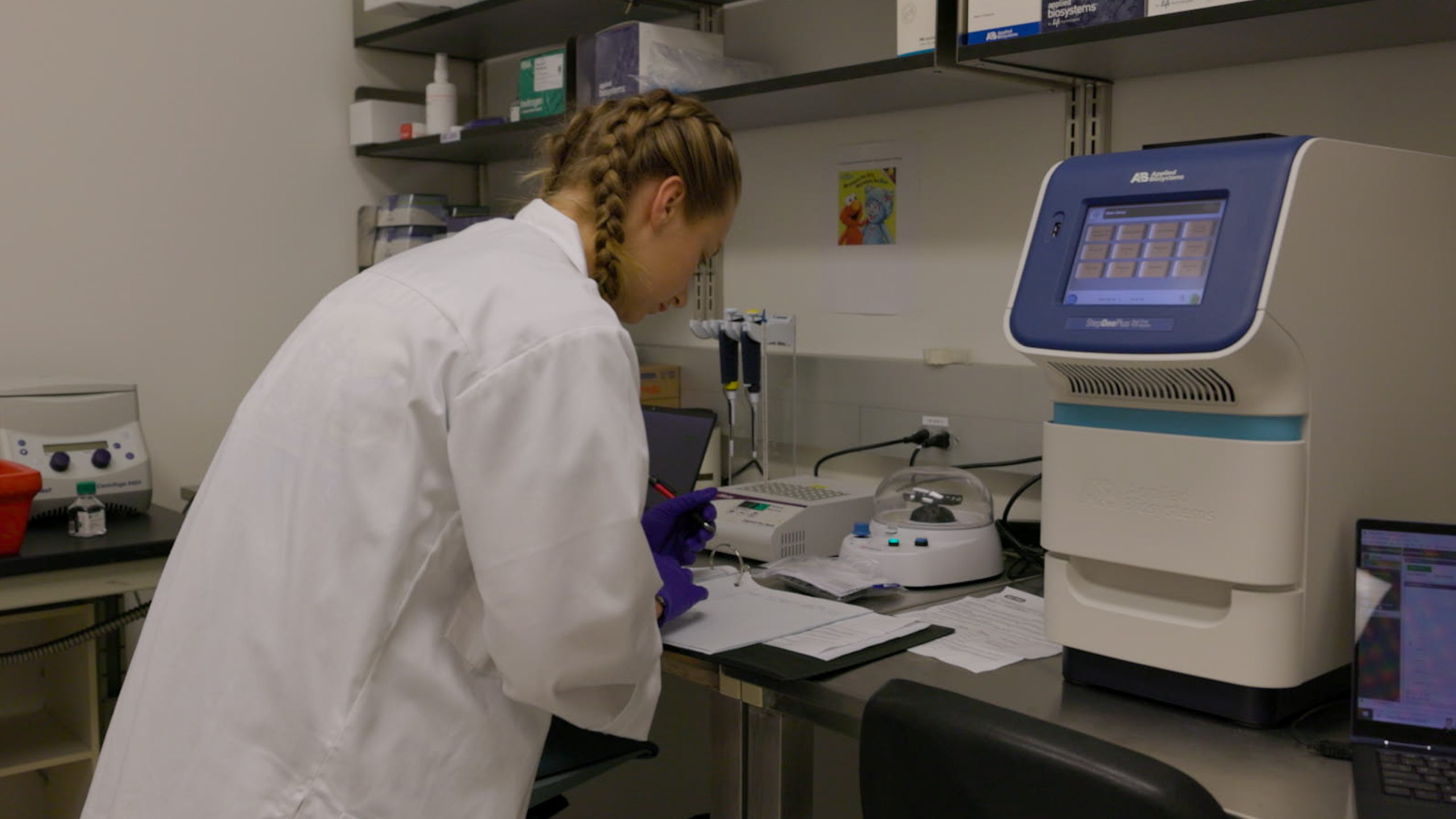

Because of the principal similarities between honey bee viruses and universal viral behaviors, even my “kids” are exploring the topic. My honey bee research students teamed up with our genetics professor to learn how to develop quality PCR testing techniques for detecting viruses in tissue samples. We were able to determine the prevalence of DWV in our own honey bee colonies. Our small study collected 22 samples from non-clinical honey bee colonies looking for DWV. PCR was performed to detect the RNA of this virus, and we found a prevalence of about 91% (20/22 colonies). This prevalence matches up with APHIS data and also demonstrates the presence of viruses within subclinical colonies. The techniques my students learned in this study can be applied in any research or clinical situation diagnosing or studying viruses in any species.

Vaccines or Treatment?

Historically, some vaccines have been a key lifesaving component to controlling viral diseases, but other vaccines have been a total flop. Currently, there are no honey bee vaccines for viruses, but research is in the works. Human and other animal species’ antiviral medications have had mixed results and practical applications over the years. A single magic bullet to eliminate viral threats continues to illude us all. So, what to do…?

New Year’s Resolution?

Wait, I thought New Year’s was in January? Years ago, many cultures started the new year in March, and for most beekeepers, this is when our season starts as well (sorry commercial guys). The best way to control viral infections is to research, learn and focus on the basic stresses that you can control, which also happen to be the best way to control viral infections in all of us. Reducing stress and promoting healthy physiology through proper nutrition and reducing co-morbidities is the key to good health. Varroa, poor nutrition, and queen issues are still the main reasons for colony loss in the U.S. If we can mitigate these three things and maintain healthy immunity in our colonies, most viral infections will remain in the background.

- Test, treat and control Varroa, which depletes immunity and functions as a vector to viruses.

- Maintain good nutrition, which provides and builds effective immunity.

- Maintain a good queen, who provides effective hive functional physiology, including immunity.

Taking biosecurity precautions, when appropriate, and using bee yard pesticides correctly, can also mitigate stress on honey bees.

So, make this beekeeping New Year’s resolution, focus on getting down to the basics and the rest will follow. And for you, be sure to ask your doc if you are getting enough Vitamin D. The sun is beginning to shine.

References to ponder for more information:

https://www.statista.com/statistics/1124915/flu-deaths-number-us/ Accessed 12-24-2024.

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/covid19_mortality_final/COVID19.htm Accessed 12-24-2024.

https://www.usbeedata.org/state_reports/viruses/ Accessed 12-18-2024.

https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/us-population/ Accessed 12-24-2024.

https://idtools.org/thebeemd/index.cfm?packageID=1180&entityID=8386 Accessed 12-18-2024.

https://extension.psu.edu/viruses-in-honey-bees Accessed 12-18-2024.

https://beeprofessor.com/deformed-wing-virus/ Accessed 12-18-2024.

Hesketh-Best, P.J., Mckeown, D.A., Christmon, K. et al. Dominance of recombinant DWV genomes with changing viral landscapes as revealed in national US honey bee and varroa mite survey. Commun Biol 7, 1623 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-07333-9

Martin SJ, Brettell LE. Deformed Wing Virus in Honeybees and Other Insects. Annu Rev Virol. 2019 Sep 29;6(1):49-69. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-092818-015700. Epub 2019 Jun 11. PMID: 31185188.

Brettell LE, Mordecai GJ, Schroeder DC, Jones IM, da Silva JR, Vicente-Rubiano M, Martin SJ. A Comparison of Deformed Wing Virus in Deformed and Asymptomatic Honey Bees. Insects. 2017 Mar 7;8(1):28. doi: 10.3390/insects8010028. PMID: 28272333; PMCID: PMC5371956.

Paxton RJ, Schäfer MO, Nazzi F, Zanni V, Annoscia D, Marroni F, Bigot D, Laws-Quinn ER, Panziera D, Jenkins C, Shafiey H. Epidemiology of a major honey bee pathogen, deformed wing virus: potential worldwide replacement of genotype A by genotype B. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2022 May 10;18:157-171. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2022.04.013. PMID: 35592272; PMCID: PMC9112108.

Traynor, K.S., Rennich, K., Forsgren, E. et al. Multiyear survey targeting disease incidence in US honey bees. Apidologie 47, 325–347 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-016-0431-0