Click Here if you listened. We’d love to know what you think. There is even a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

Figure 1: I set my BroodMinder T2SM temperature sensor on top of the frames of the bottom box. The sensor itself is the green square in the middle of the box, visible under the bees.

Part 1 – Take the Temperature of Your Colony:

Queenright Status and Brood Rearing

Theresa J. Martin

In this four-part series, we will explore how temperature sensors provide the beekeeper with actionable information that improves colony outcomes. We will review four examples: 1) queenright status and brood rearing, 2) swarming, 3) biological disruption during Varroa treatments and, 4) the value of winterizing. In all my time as a beekeeper, I have always had one BroodMinder T2SM temperature sensor in each colony, as they are critical to my beekeeping. Note that what I share is my uninfluenced viewpoint based solely on my experience and I have not been compensated in any way.

Precision Beekeeping Combined with Good Beekeeping

Precision beekeeping is using technology to improve colony outcomes. The first step is to collect data about the colony and the environment, then combine that data with expert knowledge of bee biology, seasonal trends and environmental factors. The last step is to use the information to take action that improves colony performance. The three most common types of colony data are temperature, humidity and weight, yet there are also products that report on motion, sound, vibration and thermal signature.1

Technology Overview

The BroodMinder temperature sensor system contains three technical components. The first is the T2SM temperature sensor itself, which costs $43 on BroodMinder.com (Figure 1). The sensor stores the temperature inside the hive and runs on an inexpensive, replaceable 3-volt lithium coin battery that lasts about two years. The second component is a smartphone app called the Bees App, which receives the temperature data from the sensor via Bluetooth (Figure 2). The final component is the MyBroodMinder.com website which provides detailed graphs and additional features. The website is free for less than five hives, with a subscription required for six or more hives.2

Figure 2: The Bees App showing the graph for Bandit hive on my smartphone. Seeing the graph while at the hive allows the beekeeper to take action immediately, if needed.

Example 1: Detecting and Resolving Queen Loss

Temperature sensors provide actionable information because honey bee colonies (Apis mellifera) practice thermoregulation, which is the mechanism an organism uses to maintain its internal temperature, regardless of the external temperature. A honey bee colony practices thermoregulation during brood rearing, holding the nest between 92–97°F. If there is no brood, the workers will not consume the honey needed to generate energy to hold the temperature at a constant 95°F. Instead, they will allow the temperature to fluctuate significantly.3

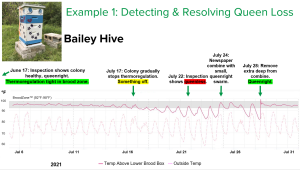

Figure 3: Detecting and Resolving Queen Loss – Because workers thermoregulate the brood nest, the temperature sensor gives an indication that a colony may be queenless, prompting the beekeeper to do an inspection to verify the queenright status of the colony. The sensor shows progress as the beekeeper works to restore the colony to queenright status.

This example describes how the temperature sensor alerted me to a queenless colony, Bailey hive, in Summer 2021 (Figure 3). The X-axis displays time, and the Y-axis is the temperature in degrees Fahrenheit. The light pink dotted line is the outside ambient temperature, taken from the weather station closest to my hive location. The solid purple line is the temperature reported by the sensor inside the hive. The gray bar labeled “Brood Zone (92°F–98°F)” is the temperature range at which the colony thermoregulates the brood nest.

On June 17, 2021, I did an inspection and found Bailey hive was in great shape: healthy with no sign of disease, a strong population of workers, plenty of resources, several frames of eggs, larvae and capped brood. During the next month, I continued to monitor Bailey hive with the temperature sensor, while also observing the bees from the outside. In mid-July, I noticed the internal temperature started to drop gradually out of the brood zone. Because it was mid-Summer, I knew this was not normal, plus none of my other 20–25 colonies were showing this temperature anomaly.

This unexpected behavior prompted me to do an inspection on July 22, and I discovered Bailey hive was queenless. There were several frames of capped worker brood, but no eggs or larvae, and minimal capped drone brood. There were no queen cells present nor a queen that I could find, so it did not appear the workers were in the process of superseding the queen. For some unknown reason, Bailey hive had become hopelessly queenless. I did not kill the queen on my last inspection 35 days earlier, because that was too long ago for there still to be capped worker brood in the colony.

Regardless of the reason, Bailey hive was queenless, so I set out to restore it to queenright status. Earlier in Spring, I caught a small queenright swarm from one of my colonies called Sunset, which has the genetics I prefer. I purposefully kept that swarm to resolve any queenless colonies I might have that Summer. On July 24, I did a combine of the swarm from Sunset hive on top of Bailey hive.4 On July 28, I collapsed the Sunset hive frames into the deep of Bailey hive, removed the extra frames, and the Sunset top deep. The BroodMinder graph showed that Bailey hive immediately started to thermoregulate the brood nest. Bailey hive went on to successfully recover through the rest of that Summer, and is still alive and productive today, almost four years later.

This example demonstrates that temperature sensors can give an indication of the queenright status of a colony. Like all beekeepers, I am busy with a full range of roles, obligations and commitments. The BroodMinder sensor tipped me off that something unexpected was happening, prompting me to prioritize an inspection of Bailey hive above the many other commitments vying for my time. Had it not been for the temperature sensor, Bailey hive may have remained queenless long enough for the population to dwindle, wax moths or small hive beetles to gain a foothold, or workers to activate their ovaries. The temperature sensor enabled me to resolve the queenless situation in time not to lose Bailey hive, as well as to monitor its recovery.

Improved Colony Health and Productivity

Maintaining queenright status is the lifeblood of a thriving, productive colony. Because of thermoregulation, temperature sensors can provide the beekeeper with insight into brood rearing and queenright status. Next month, we will look at Example 2, which is how the temperature sensor indicates a colony has swarmed.

Theresa J. Martin is the author of Dead Bees Don’t Make Honey: 10 Tips for Healthy Productive Bees, which includes a Foreword by Dr. Thomas Seeley. Her book also provides ten examples of the value of BroodMinder temperature sensors. Theresa has achieved 99% colony survival and honey production that is twice the local average in her seven years as a beekeeper, with 20–25 colonies in Kentucky. She is a Cornell Master Beekeeper, 2024 Kentucky State Beekeeper of the Year, and Vice President of the Kentucky State Beekeepers Association. Theresa can be reached at theresa@littlewolf.farm

References:

1Zacepins and Karasha (2013) provides an excellent overview of precision beekeeping as well as practical applications of temperature sensors. Zacepins, A., & Karasha, T. (2013, May). Application of temperature measurements for the bee colony monitoring: A review. Proceedings of the 12th international scientific conference “Engineering for Rural Development” (pp. 126-131). https://www.tf.lbtu.lv/conference/proceedings2013/Papers/022_Zacepins_A.pdf

2See www.broodminder.com for more information. I am not compensated by BroodMinder in any way, so what I share is on my uninfluenced experience.

3Seeley (2019) provides a full chapter about the science of colony thermoregulation, “Chapter 9 – Temperature Control.” Seeley, T. D. (2019). The Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the Wild. Princeton University Press. Stabentheiner et al. (2010) detail how a colony performs thermoregulation of the brood nest as environmental conditions change and on how workers based on age class perform different heat-related behaviors. Stabentheiner, A., Kovac, H., & Brodschneider, R. (2010). Honeybee colony thermoregulation–regulatory mechanisms and contribution of individuals in dependence on age, location and thermal stress. PLOS ONE, 5(1), e8967. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0008967

4There are several ways to restore a colony to queenright status, including a newspaper combine. For a description of the methods, see Caron and Connor (2013) pages 281-284. Caron, D. M., Connor, L. J. (2013). Honey Bee Biology and Beekeeping. Wicwas Press, Kalamazoo, MI.