By: Bill Mares & Ross Conrad

How Vermont Is Making It Work

The Story of One State’s Beekeeping History – How some Vermont beekeepers are going about it and why you should consider publishing a history of beekeeping in your state – By Bill Mares and Ross Conrad

The Story of One State’s Beekeeping History – How some Vermont beekeepers are going about it and why you should consider publishing a history of beekeeping in your state – By Bill Mares and Ross Conrad

The History of Vermont Beekeeping project began as nothing more than a whim, when at a Vermont Beekeeper’s Association (VBA) summer meeting several of us began to discuss a history of Vermont’s beekeeping as a whole.

Why write a history of beekeeping for a state? The value of history is that it can shed light on the future and the present –connecting all three aspects of time. History can also be interesting and provide us with a perspective on where we are today. Folks accepted and enjoyed their lives even though their situation may be considered primitive or uninformed compared to ours. It can also connect people with each other and help convey strength and power to those who share a history, helping to provide a sense of identity. When history is recorded it has the advantage of being analyzed easily and understood more than the present or the future. Ideally, history helps us to learn from the past (how previous generations approached the many challenges we still face today), learn from past mistakes and provide the opportunity for us to realize past dreams that never came to fruition.

In the late 19th century, Vermont State Agricultural Department reports included speeches from prominent beekeepers between the 1870’s and 1890’s. A number of beekeepers (all men) had 300-500 hives. They gave speeches which were a mixture of description and exhortation to the backyard beekeepers of the day, primarily (probably) farmers just beginning to explore how beekeeping could fit into their farm life.

In the late 19th century, Vermont State Agricultural Department reports included speeches from prominent beekeepers between the 1870’s and 1890’s. A number of beekeepers (all men) had 300-500 hives. They gave speeches which were a mixture of description and exhortation to the backyard beekeepers of the day, primarily (probably) farmers just beginning to explore how beekeeping could fit into their farm life.

In 1900, Mr. R.H. Holmes, president of the VBA reminded his audience that, “The honey season in Vermont is short at the best and the time for procuring surplus honey is sometimes limited to a few days, and in no occupation is the old maxim more true that our dish should be right side up when it rains porridge.”

Books on the History of American beekeeping (Pellett) and the World History of Beekeeping and Honey Hunting (Crane) have already been published. In this article we will describe how we are working to assemble a history of beekeeping in Vermont, and exhorting you all to do something similar in your own states.

Bill had written a book on the American beekeeping industry, so he signed up. Ross had done a book on natural treatment-free beekeeping, so he signed up. Even more germane, Ross was already working on a history of Addison County beekeeping, the Vermont region which has always been the epicenter of beekeeping in the State. To help spread the work load, Bill and Ross persuaded a backyard beekeeper (Larry Solt) and two part-time commercial side-liners (Scott Wilson and Larry Karp) to join in. Previous book writing experience is not a requirement for this kind of project, but if you have it, you at least know what you’re getting yourself into.

We ended up blocking out four logical chronological periods. They were 1780-1860; 1860-1910, 1910-1980, 1980-2016. We understand that the information will be different for each period and that each of us has a different writing style. In essence the approach we are taking is to string together four historical essays.

Each person is responsible for their own period, but whenever any of us come across something of interest, we share the information with the others.

We hope to build a narrative thread–we are telling a story after all, embellished by important people and events. The challenge is how to build that.

We hope to build a narrative thread–we are telling a story after all, embellished by important people and events. The challenge is how to build that.

Our research so far is multi-faceted. We are able to use the archives and collections of the Agency of Agriculture, the State Historical Society, the University of Vermont’s Bailey-Howe Library and collections at local museums in the Addison County towns of Ferrisburgh and Middlebury. The second block of research consists of interviews with some of the major Vermont beekeepers of our day, as well as some of the living state apiary inspectors. Third, we have notes from bi-annual bee association meetings, and a bi-weekly VBA newsletter that was published for six years.

As for meetings and coordination, our team began with a meeting over beers at a local brew pub. Since then we have communicated mostly by email.

Although we are all working relatively independently, we have agreed on some basic ground rules. The template we are all using has four variables. People, Trends, Techniques and Particular Events. We also acknowledge that no beehive or beekeeper is an island, particularly in the latter 20th Century. On the other hand, we are NOT writing a history of U.S. beekeeping and so while we may make reference to the national beekeeping climate at times, in order to provide some context for what was taking place in Vermont, our focus is primarily on what happened within the state.

Although we are all working relatively independently, we have agreed on some basic ground rules. The template we are all using has four variables. People, Trends, Techniques and Particular Events. We also acknowledge that no beehive or beekeeper is an island, particularly in the latter 20th Century. On the other hand, we are NOT writing a history of U.S. beekeeping and so while we may make reference to the national beekeeping climate at times, in order to provide some context for what was taking place in Vermont, our focus is primarily on what happened within the state.

Soon enough, we confronted the writer’s dilemma– not just what to put in, but what to leave out. Since we are not writing an encyclopedia of beekeeping, we have to keep a tight narrative. One avenue we have settled upon is the preference for vivid anecdotes over broad generalities.

Although we are all new to this type of project, we have some ideas about what you may want to consider based upon our experience so far should you decide to take on the challenge of writing a history of beekeeping in your state.

Create a budget – Decide if you will pay your writer(s) and how any royalties from the sale of the publication will be distributed. Even if you don’t decide to work with a publishing house, it’s relatively easy and inexpensive to self-publish these days but it still costs money (about $2,000-$3,000 minimum). Some potential sources of funds include state bee associations, the personal finances of those involved, and a publisher.

Identify your audience – Like rings in a pond, the impact of a history of beekeeping in Vermont is going to ripple out into the community and beyond. We are writing this primarily for our VBA members and current Vermont beekeepers. At the next level, are fellow Vermonters and historical societies who are interested in Vermont’s agricultural history, as well as libraries around the state. Finally there are people in other states who may not just find the history of beekeeping in our little state interesting, but may be inspired to pick up pen, computer and tape recorder and set out to do similar work in your state. The final potential audience is the anonymous “general reader.”

Set a deadline – you’re not in competition with anyone, but you can get stuck in the quicksand of “just one more” person, fact, idea, etc., leading you to never finish. Bill played the role of the class scold and gave us a deadline.

Decide on roughly how many pages and/or chapters – You may also want to have a rough idea of how many illustrations you want to include. Be flexible here. You don’t want to leave out critical elements or fantastic photos due to arbitrary limits.

Research – The modern computer age makes research (via internet) easy and accessible to all. Just don’t overlook old-school sources such as beekeeping books and journals, such as Bee Culture and the American Bee Journal, for articles or references about beekeepers and beekeeping happenings in your state. For example, we found a couple of references to Vermont and Vermont beekeepers in the History of American Beekeeping, by Frank Pellett. One tip is to make note of references that cite the source of your information AS YOU GO ALONG. Trying to backtrack and locate sources for your statements and facts is time consuming and can be frustrating.

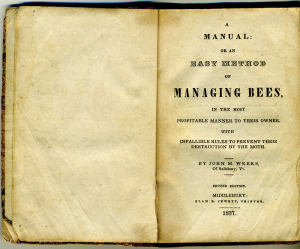

Examine documents – As indicated above, sources of agricultural records may include your state and local bee associations, government agencies, historical societies, folk-life centers, and museums. Check the archives. In the first months, we hit a gold mine at the University of Vermont’s Bailey-Howe Library’s Special Collections department, where we found biennial reports from Vermont state bee inspectors that ranged from 1910 to 2001, which gave us a solid fact-laden chronology. Not only did we find random articles about things like bee-lining and town histories about people like John Weeks of Salisbury, Vermont, but the State Agriculture Department bi-annual reports were a trove of information on inspections, diseases, pests, weather, honey yields, etc.

Always look for “characters” and their “stories” – It is the characters and stories that we believe will help make a state’s beekeeping history more interesting and accessible to the average reader. Of course you will include the large commercial and famous beekeepers that have received national attention and exposure, but don’t overlook the characters. You will find them, but not just in publications and reports, so be sure to interview your state’s beekeepers. Start with the “old-timers” that are tucked away in the hollows . . . while they are still around! They are a wealth of information, stories, and can offer a perspective that you may not find anywhere else. We have interviewed a number of professionals and side-liners as well as two state beekeeping inspectors, who between them, covered the last 35 years. Ross interviewed members of two prominent beekeeping families the Manchesters of Cornwall, Vermont and Mrazes of Middlebury. (See the December 2015 issue of Bee Culture). From them came suggestions and stories about the previous generation of beekeepers, some of whose names had turned up in the State reports.

Hire a professional editor – None of us write deathless prose; we need that objective eye. Just be sure to include the cost of an editor in your budget since unless you have a professional editor in your beekeeping organization, this is where most of the money is likely to get spent.

The History of Vermont Beekeeping is a work in progress and our hope is to have it published sometime in 2018. Such efforts especially if duplicated in other states will go far in helping to document and save our state’s beekeeping histories . . . histories that often get glossed over when the focus is on a national or global level.

As far as we can tell, if we are successful, Vermont will be the first state to publish its history of beekeeping. However, we hope we will not be the last. We encourage those of you who decide to take on such a project to remember that one size does not fit all, but quilts all look alike from a distance.

In the early 1980s Vermont State bee inspector, Rick Drutchas, came upon some abandoned hives full of American foulbrood. He told the farmer’s son that the hives were a menace and he would have to return to destroy them. “Whatever,” he said.

Drutchas continued: “In about two weeks I came back with my assistant Dick Brigham. We knocked on the door and the farmer’s son comes to the door. He looked as if he had been crying. I told him we were here to burn the hives and we’d talked to his mother about it.

“He turns and pointed toward the living room and there she was laid out on the sofa, dead.

“Really embarrassed, we said, ‘Oh, my Gosh, we’ll come back later!’

“But outside, Brigham said, ‘Let’s not wait, let me talk to this guy.’

“So gently but insistently he told the son that we’d dig a hole, bury all this equipment and burn it up and he wouldn’t have to worry about it.

“Then the son said, ‘Well, we could use tractor to dig the hole. And would this be today?’ he asked.

“Absolutely!” Brigham said.

“The son started to smile, and he said almost to himself, ‘Won’t that make the neighbors think!’”