Read along below!

Winter-Killed Colonies – Cleaning Up and Recouping

The Phoenix Beehive – arising from the ashes…

By: James E. Tew

Winter-killed colonies are a beekeeping fact. It seems that no matter how dedicated an effort one makes, there’s always a colony that is insistent on dying. I’ve made previous references to one such colony of mine. The particular colony seemed to have everything needed for successfully wintering.

Some Hive Requirements for Successful Wintering.

- A young, productive queen.

- Honey stores that are correctly positioned. (Amount varies with location but generally 40-65 pounds of honey.)

- Four – five frames of pollen near the brood nest.

- Strong population of healthy bees (50,000+).

- Basic hive manipulations performed (e.g. entrance reducer installed, inner cover reversed, and upper ventilation and upper entrance provided.)

- Protected location.

In general, my colony in question had no business dying, but it did. During late Winter and Spring, it’s a common beekeeper question at meetings. “What did I do wrong?” Most of the time, it was something routine, like starvation or a queen dying, but sometimes good colonies just die and we will never know why. Poor wintering genetics can play a major role. A particular colony looks good in the Fall but turns up dead in the Winter. Sometimes you lose.

The Dead Colony’s Autopsy.

Wax Moths, American Foulbrood and Nosema.

Depending on the location of the beekeeper, various procedures are required to recoup Winter losses. In warm climates, the wax moth is a relentless taskmaster. The combs are often destroyed before the colony is completely dead. Warm climate beekeepers must be doubly alert or their problem is compounded – they have lost bees and comb. In cooler climates, the situation is still bad, but not so urgent. The first thing a beekeeper should do with winterkilled equipment is to determine what caused the colony to die. The obvious concern is that spore-forming American Foulbrood (AFB) may have been the problem. If foulbrood has been a problem in the past, the beekeeper should contact the state apiary inspector and have a competent assessment made. At times, Nosema is a problem. Unfortunately, Nosema is difficult to diagnosis and the remedy is somewhat expensive. Excessive defecation spotting is an indication of dysentery.

Mites.

And there are always mites. A mite-infected hive is a good candidate for becoming a winterkill. After refurbishing, equipment from a hive killed during winter months, or any month for that matter, can be safely reused.

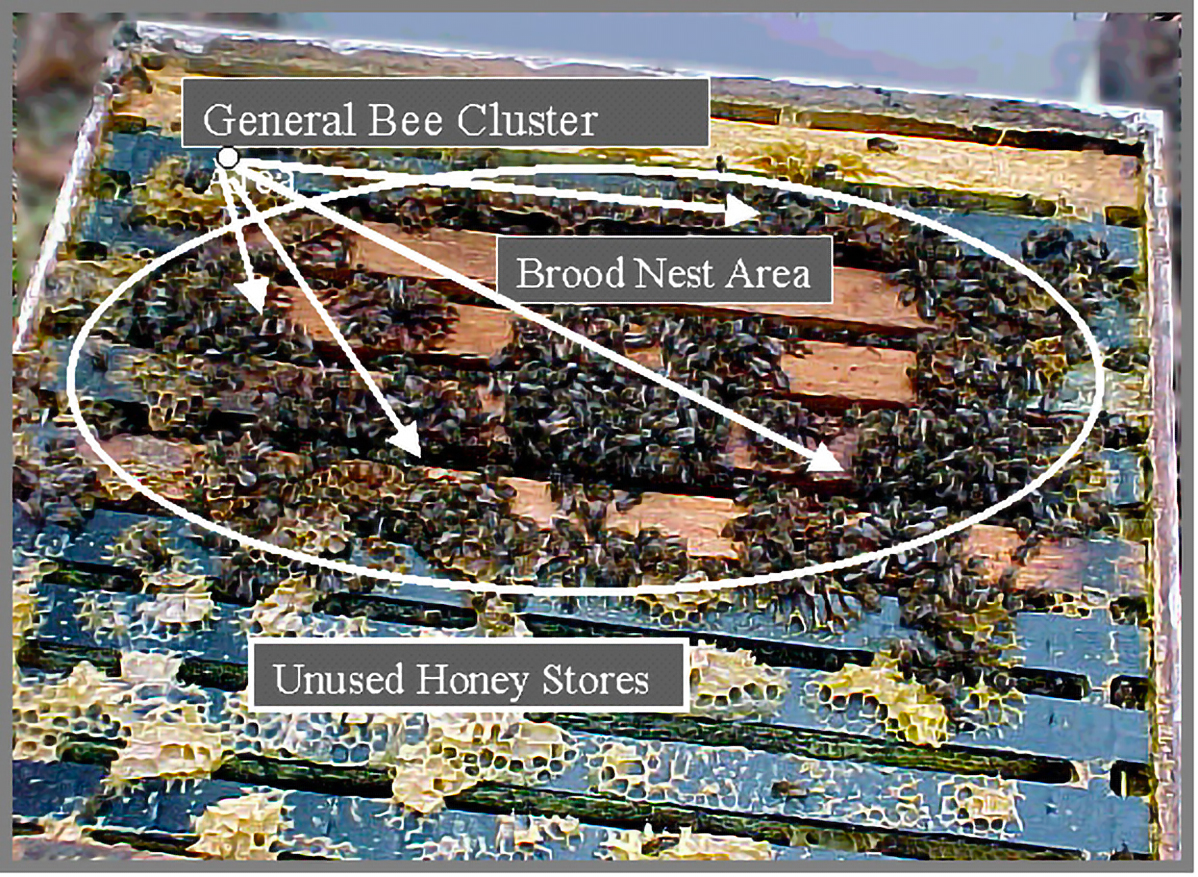

Starvation.

Starvation has distinct characteristics. The cluster will be in a tight (and dead) group, probably near the center of the colony with single dead bees scattered about. Upon removing frames from the colony, many bees will be seen in cells with their heads toward the center of the comb. Meager amounts, of any honey will be in the colony. Occasionally, patches of honey will be found scattered throughout the colony, but bees were unable to get to it before chilling.

Once the reason for the winterkill has been determined, the beekeeper must then decide what to do with the equipment. Diseased equipment should be destroyed or sterilized depending on the disease pathogen. Colonies that starved should have dead bees shaken from the equipment and comb as much as possible. True, new bees will remove all the dead bees from the equipment, but critical time can be saved by assisting the bees with the task.

Re-Establishing Hives.

Spring Colony Splits.

Most beekeepers want to restock their winterkill equipment. Several techniques are possible. Unless the beekeeper has had extremely bad luck, some hives probably survived the Winter. Depending on the strength of the surviving colonies, bees and brood can be taken from surviving colonies, along with a new queen, and put in refurbished winterkill equipment. The strength of the split is an arbitrary decision the beekeeper must make. The stronger the split, the more likely the colony will survive the Winter. However, the stronger the split, the more likely the beekeeper will not get a honey crop from the original colony.

Provide Mated Queens.

I would strongly suggest placing a mated queen in the re-established colony as opposed to letting the bees produce their own. If winterkills have been a problem, one should do everything possible to improve his or her techniques for the next winter. Too much time is lost during the nectar flow if bees are required to produce their queens. Brood and bees from several colonies can be mixed to form a new colony. Smoke or some other disruptive agent (air freshener or newspaper barriers) should be used to mix the bees from different colonies to minimize fighting.

Buying Package Bees.

Another common technique for restocking hives is to purchase package bees. This is a simple and proven procedure for getting colonies back into operation. Package producers, listed in the bee journals, should be contacted as early as possible in order to book the arrival date most convenient for the beekeeper. If bees are all that’s needed, queenless packages can be purchased. Colonies that survived the Winter in a weakened condition, but alive, can be boosted with the addition of a few pounds of healthy adult bees. Contact individual package procedures for the details on queenright or queenless package purchases.

Buying Colony Splits.

Colony splits have the advantage of not having the “Post Package Population Slump.” After a package of bees is installed, the adult population declines until new bees are produced by the colony. Since brood is included in a colony split, the adult population declines until new bees are produced by the colony. Since brood is included in a colony split, adult population decline is not as great. Subsequently, the colony builds up faster and is better prepared to withstand the upcoming Winter.

To the best of my knowledge, there is not “standard” split. The beekeeper must contact other beekeepers that are selling splits to determine how many frames, how many adult bees, and how many developing bees will be in the split. The buyer should also determine if frame replacements are required. It would probably be a good idea to check with the state inspector to be sure the individual has a good record of disease control. Occasionally special deals may be worked out with another beekeeper for the purchaser to provide the manual labor required to make the splits. It makes sense that on-site pickup of the splits will considerably reduce the cost of shipping (assuming there’s no long drive involved).

Swarms.

I seriously doubt that there’s a beekeeper anywhere in the world that doesn’t have a slight rise in blood pressure at the mention of a 6-pound swarm. In fact, swarms are an excellent way to restock winter killed hives. The only problem is that they are so unpredictable and, due to mite predation, they have become somewhat uncommon. They are also inaccessible at times – requiring great feats of strength, bravery, and agility (maybe other descriptive terms would have been more appropriate here). The point is that they are sometimes simply not worth the risk. Another confession? Sometimes I hold some winterkill equipment for the swarms that comes my way. I’ve had reasonably good luck with the low-labor procedure.

The “Dead-Outs”

“Dead-Outs” are simply colonies that died during the Winter – whatever reason. There are few reasons to wish for colony winterkills, but if it happens, the beekeeper has a window to perform routine hive maintenance and late Winter busy work.

Fix and repair.

Old or Busted Frames.

Increasingly, I am agreeing with those people, who years ago, were recommending the disposal of old, dark combs. Use common sense here. If the frame is still perfectly useable, then use it, but if it needs extensive repair, is distorted, or has a lot of drone cells, toss it. Actually, they make great kindling for a fire to keep you warm while working. Don’t burn the plastic inserts.

The reason for my change-of-heart is the possibility that pesticides are accumulating in old wax and the increased concerns about old combs harboring viral and bacterial pathogens. My general recommendation…use old comb, but don’t become attached to it.

Scrape Propolis and Burr Comb.

Bees busily apply propolis in the Spring; you busily remove it during the Summer and Fall. While the frames are out, scrape propolis and burr comb so the frame fits more cleanly in the hive body. I’m not sure why, but I always save the propolis scrapings. I’ve never sold any, but I confess that I do like the smell of fresh propolis.

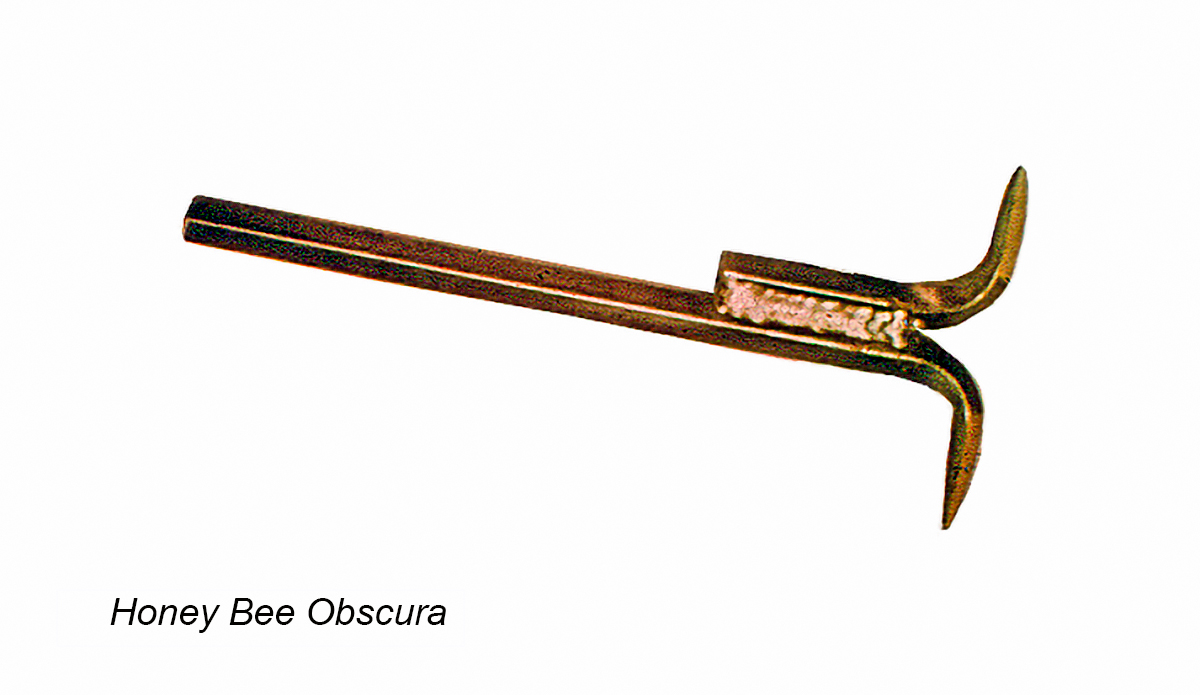

The propolis and wax scraper shown in Figure 3 is built from two 5/16” Allen wrenches welded together. One wrench is cut off to allow a wooden handle to be fitted if desired. The outer ends of the wrenches are ground to a knife edge and ground on the sides to fit the rabbet in supers and hive bodies. The tool makes quick work of scraping out propolis and wax from rabbets and corners of hive equipment.

Repair and paint.

There will never be a better time to scrap, repair, and paint the hive equipment. It’s cathartic. From a dead hive, you remodel, restore, and reinstall a new colony. I feel frugal, but a radio and a warm fire help with potential boredom during this winter task. If you mark or brand your equipment, do it now, just before repainting.

The Phoenix Beehive

From the bleak disappointing death of a colony arises the birth of a new, refurbished colony in a clean hive. But not too many deaths. High Winter colony losses are indicative of management procedures that need to be improved. But you should be prepared for some colony deaths each year. In fact, all beekeepers can expect some winterkills during some years. Take it in stride and prepare the equipment for the re-establishment of a new colony the next Spring. Thoughts of spring can make the coldest winter day more tolerable.

Dr. James E. Tew

Emeritus Faculty, Entomology

The Ohio State University

tewbee2@gmail.com

Host, Honey Bee

Obscura Podcast

www.honeybeeobscura.com