From the University of Florida Honey Bee Research and Extension Laboratory

What Does It Take to Run a Honey Bee Laboratory?

By: Chris Oster, Steven Keith & Devan Rawn

January: Overview of the HBREL at UF

February: Honey Bee/Beekeeping Teaching Programs

March: Research on Honey Bees

April: Apiculture Extension (Part 1)

May: Apiculture Extension (Part 2)

June: Roles in a Typical Honey

Bee Lab

July: How Labs are Funded

August: The Lab’s Physical

Infastructure

September: What it Takes to Run a Laboratory Effectively

October: Professional Development

in the Lab

November: Members of the HBREL Team and What They Do

December: The HBREL’s Most

Notable Successes/Contributions to the Beekeeping Industry

Part 1. What Any Lab Needs

My name is Chris Oster (Figure 1), and I am the Laboratory Manager at the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Science (UF/IFAS) Honey Bee Research and Extension Laboratory (HBREL). In this article, two of my colleagues and I will report on the day-to-day operation of a honey bee research laboratory. My laboratory colleagues who authored the previous articles in this series have already covered who does what in a research laboratory (June) and how laboratories receive funding (July). Here, we will focus on what is needed, both in materials and labor, to achieve our teaching, research and extension goals.

As the laboratory manager, my job is to ensure that everyone else at the HBREL can do their jobs. What that task includes is different depending on the team member with whom I am working. The November article in this series will cover the members of our laboratory, but briefly, our laboratory is administered by three faculty members: Dr. Jamie Ellis, Dr. Cameron Jack and Ms. Amy Vu. Dr. Jack and Dr. Ellis both have graduate students who they mentor and technicians who work for them. Amy has a team composed of project coordinators who help her with her extension programs. We also benefit from the small army of UF students and local beekeepers who volunteer at our laboratory. Each faculty member has different programmatic goals, and how each achieves those goals varies widely.

In our laboratory space (Figure 2) alone, we have hundreds of pieces of equipment that all need to be in working order. If a graduate student or technician needs to use a scale, it is my job to ensure that they can choose any scale and that the scale will be in good working order, meaning it is calibrated and will deliver an accurate measurement. This extends to pipettes, microscopes, freezers, refrigerators, incubators, glassware, DNA extraction equipment, fume hoods and so much more. For a scientist to obtain accurate results, they need to be able to trust their equipment, space and test subjects. To achieve this, scales and pipettes need to be calibrated and cleaned regularly. Freezers need to be defrosted and monitored for failure. Bench spaces and tabletops need to be cleaned to avoid contamination or injury. Glassware needs to be cleaned regularly. Chemicals need to be maintained through proper storage and disposal. Personal protective equipment needs to be available and used. All these things, plus about 10,000 others, are what it takes to keep just our laboratory space in working order.

Researchers are the most vital part of any research laboratory. For everyone who is part of the HBREL, including faculty, staff, students and volunteers, training is a major must-have. Especially critical are trainings to deal with hazardous chemicals in the laboratory and dealing with heat and heavy lifting in the field. All personnel must receive proper training. Luckily for us, the University of Florida offers hundreds of online and in-person training courses. As the laboratory manager, it is one of my duties to ensure that everyone is up to date on all their training. Additionally, new technicians, students and volunteers all need to be trained in how to use our equipment and our workflow practices. For example, we maintain a colony of small hive beetles in the laboratory for bioassays or honey bee colonies we call our “mite factories” that can sustain over 10 times the Varroa destructor treatment threshold. To conduct our research on the mite and small hive beetles, we need a lot of them. A typical bioassay might require 250 healthy mites or small hive beetles, and we can conduct several of these bioassays each week. Maintaining the colonies that support these pests requires training and dedication from our volunteers and staff.

Aside from the people and the spaces, our laboratory needs materials and supplies. Part of my job is to support HBREL staff to ensure they have all the equipment, materials and supplies necessary to conduct their projects and programs. I keep a spreadsheet of all the purchases I have made for the laboratory with my university procurement card. That list is currently over 500 items long from dozens of vendors in just the last two years. These purchases are anything from chemicals for the laboratory, hive tools and veils for our undergraduate students, to hotels and registration fees for academic conferences. For any laboratory to be successful, it needs to have the means to purchase these items (see our July article for more on this), and the infrastructure to store and use these materials (see our August article for this).

Many of the things I have discussed so far are not unique to our laboratory, but what is unique to us, or at least the laboratories in our field, is our need for honey bees. Not only do we need hundreds of honey bee colonies, we also need colonies of varying sizes, strengths and pest and virus loads on demand. Keeping bees alive and studying them is the subject of the remainder of the article and will be covered by our laboratory beekeeper, Steven, and our lead field technician, Devan.

Part 2. The HBREL Beekeeper

Hello! My name is Steven Keith, (Figure 3) and I am the laboratory beekeeper at the HBREL. I am excited to share some information about my work at the laboratory and explain how it contributes to the extension programs we offer and research that stems from it. You may be asking yourself—why does the laboratory need a beekeeper? Don’t all the researchers know how to keep bees? While most of our researchers are indeed experienced beekeepers, there is a lot of work that needs to be done behind the scenes to ensure the colonies are maintained in optimal condition, and the apiaries at the HBREL are equipped with everything our team needs to conduct accurate and efficient research.

Efficiency is something in which I am particularly interested. In my role, I am constantly asking, “how could I make this process faster and easier for beekeepers,” “how could we manage more hives with these same processes,” and “how would a commercial or backyard beekeeper do this?”. I work to ensure that all our beekeeping materials, apiary management tools and apiary facilities are organized in a way that makes it easy for our researchers to initiate and conduct new research projects. In that capacity, I have the pleasure of working closely with the HBREL Laboratory Manager (Chris Oster) and the HBREL Field Technician (Devan Rawn) to shape our apiaries around the needs of individual research projects and furnish healthy, stable bee colonies for our researchers to study. In addition, we need to have hives readily available for groups that tour the laboratory and for all the extension classes we have throughout the year.

I began beekeeping as a hobbyist in 2017 and quickly became obsessed with bees and the beekeeping industry. I have been fortunate enough to work in a variety of beekeeping settings, including managing a sideline apiary, conducting humane bee removals and re-homing feral colonies, and working alongside an experienced honey producer. Those experiences helped inform my work at the HBREL, where I look for opportunities to create systems that will benefit beekeepers of all levels with their apiary management. I enjoy spending time in the field checking colonies and observing the bees, but I also love the tools that we use at the HBREL to increase our efficiency, such as our small fleet of vehicles, heavy machinery, freezers, feeding systems and hive equipment (Figure 4). My goal is to ensure that our HBREL team always has what they need to conduct a new project, teach a class, perform outreach and extension or a hive demonstration for a tour. This especially includes the bees themselves and everything necessary to keep them alive!

My job is focused on the work needed before a project begins to ensure that it can run effectively and yield reliable results. Each year, the HBREL apiaries house between 100 to 300 colonies (Figure 5), some of which are in studies, and some are recouped after a research project or maintained as support colonies. It is imperative that the laboratory have sufficient hives available to conduct a research project; if there are not enough colonies for a project, then research cannot happen. Hive management includes feeding the bees, monitoring for queen cells to reduce swarming, monitoring the parasite loads within the hives and performing splits as colonies grow (Figure 6). During periods where there is an abundance of nectar, bee colonies may attempt to swarm, resulting in colony losses. When a colony displays the signs of imminent swarming, I need to be ready to intervene quickly. To manage the hives optimally, I also need to be aware of the forage available to the colonies at each of our beeyards to ensure that there is sufficient food available for the colonies there. I must also be sure that beekeeping materials such as hive bodies, frames, queen excluders and nucs are readily available to the other HBREL members. When necessary, I re-queen colonies to optimize the genetics of our hives. Lastly, I manage the schedule of pest and disease treatments when they are not in a study.

As much of the HBREL’s research involves studying honey bee pests and pathogens, I work to maintain colonies of those pests so that they are available to our researchers when needed. For example, we are working on a project to determine which miticide is most effective in reducing Varroa populations in a colony. Part of my role in this project is to provide my laboratory colleagues with a group of colonies which carry a high mite population, meaning that I need to manage those colonies to keep Varroa numbers high, without allowing the colonies to decline. While this type of management may seem counterintuitive, it is important that I maintain a high Varroa load in those select colonies so our team can measure the decline of mites caused by each treatment. In this regard, managing bee pests is just as important as managing the bees themselves. Our teams need to be sure that they have sufficient pests available to conduct their research projects. Understanding these pests can eventually allow beekeepers to learn how to alleviate the stress these pests place on their own colonies.

This work requires focused inventory management. Much of my work involves ensuring our beekeeping resources are kept organized and accessible to the people who need them. I manage the large workshop facility within the HBREL campus. The facility houses our walk-in freezer (to hold drawn combs and honey frames), all our unused hive bodies and hive components, our pallet jack, forklift and other warehouse management equipment. This list does not even include many other tools used in our hive management and beekeeping education. I develop efficient systems for producing and distributing feed to our apiaries. I move resources between hives to give colonies what they need to remain healthy until they are used in a new project. I also maintain the seven apiaries located outside of the HBREL facilities. This includes mowing, preparing the yards with stands and pallets, transporting colonies between yards and maintaining equipment in the field.

My work is highly impacted by the season and the flows of nectar and pollen that we experience in the Gainesville and Central Florida area. In our region, Spring blooms lead to sharp increases in nectar and pollen availability, and our hives increase their populations rapidly. To avoid swarming and hive losses, I ensure that every hive in every apiary is checked weekly to remove queen cells and perform splits as needed. In the “slower” times of the year, particularly in Winter, on top of ensuring the colonies are well fed, I can turn my attention to annual maintenance of the beeyards, such as trimming back overgrown areas and making the apiaries more accessible. During this time, I look for new apiaries, as our research sometimes requires different access to forage or proximity to other resources. Winter is perfect for maintaining equipment, cleaning ‘dead-out’ hive boxes, repairing broken equipment, servicing heavy machinery and organizing the workshop. During a typical year, I work with volunteers who donate their time to help with hive and facilities management. This is one of the most enjoyable parts of my job, as I have the honor of teaching many new beekeepers the basics of apiary management and help them learn some of the ‘tricks of the trade.’ Twice a year, I have the pleasure of preparing and teaching courses at our bi-annual Bee College event (Figure 7), where I teach the basics of hive construction, beekeeping tools and hive inspections.

Figure 7. Steven Keith teaching at UF/IFAS Bee College in the HBREL workshop. Photo Credit: UF/IFAS Communications

Whenever possible, I work to increase my beekeeping skill set so that I can make the HBREL more resilient and better positioned for future research projects. This year, I have been focusing my efforts on queen rearing and becoming more informed about bee breeding and genetics. My hope is that by constantly improving our management practices and my own beekeeping knowledge, we will be able to conduct high quality honey bee research projects each year and make more of that research available to the community of beekeepers we serve.

As a team member who is in close contact with the HBREL’s honey bee colonies every day, I am excited about our future and the excellent research being conducted here. At my core, I am a beekeeper who is passionate about maintaining healthy bee colonies and making beekeeping accessible to anyone. I am grateful for the opportunity to contribute to these efforts through the work of the HBREL. I hope that my efforts to manage our colonies and facilities will eventually result in better, easier beekeeping for everyone. If you find yourself around Gainesville, Florida, I hope you will take the time to stop by and allow me to give you a tour! Bring a veil with you—you never know when we might need to split a colony or check for queen cells, and I would be happy for you to join. Next, my colleague, Devan, will explain what he does as our leading field technician.

Part 3. Role of a Field Technician

My name is Devan Rawn (Figure 8) and my position at the UF/IFAS HBREL is the lead field technician. My focus is on research projects and data collection with our bees in the field. I also lead technical management of hives to prepare colonies for trials. I am originally from Ontario, Canada, where I have previously worked as a research technician for our provincial beekeepers’ association and other honey bee organizations. I also spent time managing my own colonies for honey production and commercial queen production. I work closely with Dr. Ellis, Dr. Jack and their students to provide input on experimental design and methods that will allow us to meet our research goals. I manage some of our hives as they are used within trials, and I typically work with our beekeeper, Steven, to ensure our colonies are ready to enter a project. Once a new project begins, I maintain it through the duration of the study to completion.

Before a particular research project initiates, hives often need to be prepared in a specific way. This is where the field technician and our laboratory beekeeper really become collaborative. We need to coordinate to understand how many hives are available and in what condition they are. Varroa infestation levels are always critical to a research project. Even if the research does not concern Varroa control, the colonies must be monitored regularly. If there is a research project involving Varroa control, it is helpful if the mite levels are elevated. If we are sampling mites and constantly finding zero or just one mite in our samples, it will be difficult to know how well a treatment works. For this reason, we are often trying to maintain colonies with mite levels around or above the treatment threshold, as Steven previously mentioned.

The overall strength of individual colonies is another key factor that must be addressed before initiating a research project. Sometimes, four to five frame nucs might be the best colony unit to use in a research project. At other times, we may want to observe a colony in double deep brood chambers with a population of twenty frames of bees. Before a trial begins, our team will often manipulate colony strength by moving frames of bees and brood between hives. This is also known as “equalizing,” a common job for many beekeepers, to standardize the strengths of colonies in a location. We may do the opposite in some cases and create some colonies that are much stronger than others and divide these amongst our treatment groups. This depends on the goals of the research and the protocols that our principal investigators (the researchers) have established.

A field technician’s job often involves some trial and error. If there are established methods that have been used in similar trials in the past, I will review that literature and see if those exact methods will fit the goals of our current research. Often, there are some modifications to previous methods that we hope will make our research more accurate or would make the methods more applicable to our current projects. This is where I will collaborate with and provide feedback to our principal investigators if they cannot be in the field with me. We work as a team to ensure our research goals will be met, and the projects can be done accurately and reliably.

Research projects may require specialized equipment. Screened bottom boards for counting mites could be preferred if we want to measure how effective a treatment is within 72 hours. Conversely, we may choose to put our colonies on four-hive pallets that can be easily picked up with a forklift if the research will involve moving colonies often. Our queen rearing efforts require a substantial amount of unique equipment and the queens we produce may be required for certain experiments. It is helpful for a technician to be familiar and comfortable with a wide range of beekeeping accessories. When the researchers want to design an experiment that will benefit from a new piece of equipment, ideally a field technician can fabricate or re-purpose something to meet the research objective.

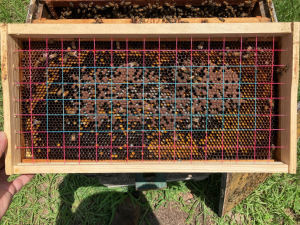

Observing colonies and making measurements for data collection can be difficult. Often, field level research involves many colonies, and trying to discern slight differences between groups of colonies. Obviously, it would be ideal if we could always detect significant differences in research trials, but that is not a reality, and we must work hard to observe and record any effects. Over the years, the faculty members at our laboratory have used an amazing number of tools and pieces of equipment to meet their research goals. Recently, I used a grid placed over brood frames, to estimate the area of comb containing pollen or capped brood (Figure 9). Methods like this require more of a technician’s time, but they may be critical to measure even the slightest differences between treatment groups. Colony weight is another data point that we often collect. It can be used purely to estimate honey production, or to observe a colony’s efficiency during a period of dearth. Either way, weighing colonies can be a tiresome job. Our workshop has scales of all kinds, from ones that a hive sits on permanently, to a mobile tripod that we can hoist hives with and weigh with a hanging scale. The small hive beetle (SHB) is a common pest for us in Florida. We are actively researching SHB but are also forced to deal with it in our hives, as would any other beekeeper. When it comes to unique equipment and gadgets, SHB traps are among the most plentiful. I have tested different methods for monitoring SHBs in Florida. Sometimes we need to collect SHB adults alive to bring them back to the laboratory and provide our technician or other researchers with specimens. In this case, we typically use “aspirators” that allow us to create suction to catch adult beetles in a container and return to the laboratory (Figure 10).

Once a research trial has begun, my job is to collect data according to the methods on which we have all agreed. This can involve long days, in variable weather, but it is important to do this reliably and consistently. If something must change or does not go according to the original plan (understandably so with honey bees), the most critical point is to make detailed notes and do everything I can to document the situation. I am responsible for getting the data backed up at the laboratory so I can then pass it along to Dr. Jack or any other analysts who will interpret the data.

Figure 10. Traps for small hive beetles. These can be used in various research projects. Photo Credit: Devan Rawn

Hopefully, I have provided an understanding of a technician’s life here at our bee laboratory. It can be challenging, but that is part of the fun. It is always a collaborative and thought-provoking job that makes me appreciate honey bees more with every project we undertake.

In the same way a honey bee colony has its division of labor, so does the UF/IFAS Honey Bee Research and Extension Laboratory. Seamless coordination, extensive resources and dedication to the team mission are all required to achieve the goals of the superorganism that is our laboratory. Without the individuals filling the roles in each niche of our operation, there would be no HBREL. We strive to be as optimally functioning as the creatures whose lives and health we hope to improve with our efforts.