Honey bees may be dying at an unprecedented rate this winter, with more than 1 million colonies lost, according to a survey of U.S. beekeepers by the nonprofit organization Project Apis m. More than a dozen government and academic scientists have mobilized to search for the cause.

Honey bees may be dying at an unprecedented rate this winter, with more than 1 million colonies lost, according to a survey of U.S. beekeepers by the nonprofit organization Project Apis m. More than a dozen government and academic scientists have mobilized to search for the cause.

Commercial beekeepers reported that, on average, they lost 62 percent of their colonies from June 2024 to February 2025, according to the survey. The organization gathered data from 702 beekeepers nationwide in January and February. Their operations account for more than half of honey bee colonies managed in the United States.

“We moved quickly to gather information,” said Danielle Downey, executive director of Project Apis m. “We don’t really know what’s going on, and a catastrophic loss could happen again.”

Respondents have lost 1.1 million colonies from late summer through winter, according to the data. Those losses account for 41 percent of total colonies in the United States, Downey said during a YouTube livestream Friday that covered survey results.

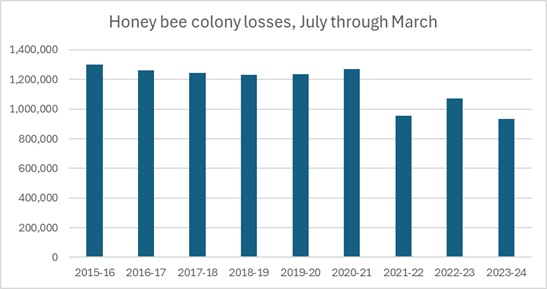

Those figures do not substantially differ from data reported by the USDA, which has reported colony losses that range from 933,000 colonies to nearly 1.3 million colonies from July through March in the last decade.

“We believe this to be an underestimate of these losses,” Downey said.

Source: USDA

As of January 2024, beekeepers maintained 2.7 million honey bee colonies nationwide, according to survey data of operations with five or more colonies from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Preliminary sampling of live and dead bees has failed to show a cause, and a team of at least 16 scientists from universities and the USDA are looking for answers. The survey from Project Apis m. covered whether the bees were stored indoors or outdoors over winter, whether queens had been replaced in lost colonies, whether beekeepers had supplemented their nutrition and how many colonies were afflicted by Varroa mites.

For each of these variables, Downey said, no clear pattern emerged.

In the next few months, government and university researchers will analyze samples for pathogens, pesticide residues, microbiome and host-pathogen interactions as well as metagenomic analysis.

In some cases, Downey said, the labs will place priorities on the 500 samples that were collected in February from colonies from around the country that were transported to the almond pollination in California.

Beekeepers who send colonies to the California almond crop were the first to sound the alarm. That crop is the first to require pollination services in the nation. Downey said that beekeepers first noticed higher-than-expected mortality rates when they checked the colonies before transporting them, then were surprised with sudden die-offs of the bees after they were transported, seven to 10 days later.

“They had huge losses in the sheds, and they continued to have losses on the way to California,” Downey said.

Chris Hiatt, a past president of the American Honey Producers Association who runs beekeeping operations in California, North Dakota and Washington state, has never stopped sounding the alarm.

“Over the last 20 years, it gets worse and worse,” he said. “It seems like it doesn’t matter what you do” to try to keep the bees alive.

Chris Hiatt, past president of the American Honey Producers Association

According to annual surveys by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, losses from late summer through spring have ranged from 933,000 from July 2023 through March 2024 to 1.3 million in 2015 through 2016.

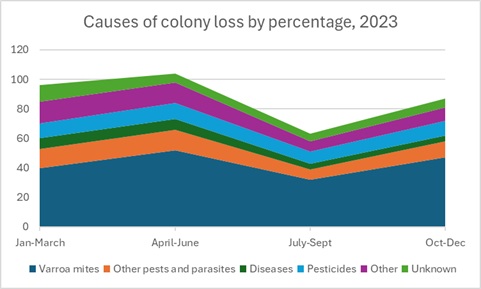

In 2023, the most recent full year for which data were available, the leading cause was infestation of Varroa mites, followed by other pests and parasites, pesticides, diseases and factors such as weather, starvation, queen failure and insufficient forage.

Source: USDA

Meanwhile, Hiatt said the days are long gone when he and his father would find 5 to 10 percent of the colonies dead at the end of winter. He considers his own operation fortunate with colony loss at 31 percent this year.

“It’s not sustainable overall,” he said.

During the livestream Friday, Downey pointed out that colonies cost about $200 each to replace, and that high losses could drive more beekeepers out of business.

“If these businesses can’t stay solvent, there is no backup plan,” she said.

She also said that one in three bites of food depends on pollinators to produce.

“If you like food, you need bees,” she said.

To view original article visit: https://usrtk.org/bees-neonics/beekeepers-report-catastrophic-winter-losses/