My Failed Attempt at Citizen Science

James Masucci

I have been a scientist my entire adult life. Even though I’ve retired, I still think like a scientist. I constantly ask “why” and “how”. I am always trying to improve my bee operation. I am also very skeptical about what I read and what I am told. “Wait, skepticism? Isn’t science supposed to provide all our answers,” you ask? Science doesn’t prove anything, it only provides clues. Scientists try to provide meaningful data to solve life’s puzzles. But the scientific literature is fraught with misinterpreted and over-interpreted data. You see, life’s puzzles are infinitely complex and we can only use our limited knowledge to design what we think are good experiments to explain them. We generate data but may not understand everything that impacted the data. What we rely on are other scientists asking the same questions and getting the same results. It’s when you have a large body of evidence that your start to believe. The problem comes when the first bit of evidence gets taken as truth and nobody bothers to follow-up. Look at varroa. For decades people believed mites fed on hemolymph. Years ago, Dr. Allen Cohen, the guru of insect diets, told me there is no way varroa feeds on hemolymph. Not enough surface area in their digestive tract. It wasn’t until Dr. Samuel Ramsey was told about Dr. Cohen’s hypothesis by Jerry Hayes and did his experiments several years later that we learned varroa feeds on fat bodies.

It was with this healthy skepticism that I heard Kaira Wagoner and Phoebe Snyder present their data on UBeeO (unhealthy bee odor). They mimicked/reproduced the pheromone that unhealthy brood emits, triggering hygienic bees to remove the unhealthy larvae. If this were true, I recognized that this could be a real queen breeding tool. So, I wanted to test it. I also knew that I didn’t have the resources to test it properly, so I put out a request in Bee Culture for people who were going to try UBeeO to share data with me. My hope was, that together, we would generate enough data so that beekeepers could make informed decisions as to whether it was worth using in our queen production programs.

There were four of us in the St. Louis area that were going to test 140 hives and six other beekeepers responded to my request. Together, we would have over 200 colonies, enough to have a decent experiment. The experiment was in two parts and was designed to ask three questions: 1. What is the frequency of the trait in our unselected colonies? 2. Do colonies scoring high for hygienic behavior have lower mite counts? 3. Does grafting from high-scoring colonies increase the frequency of the behavior in your population (can you use it as a breeding tool)? The trial was in two parts. First, test colonies with UBeeO and, prior to mite treatments, determine the mite loads. These data address questions 1 and 2. Next, graft from high scoring queens, preferably in a mating yard with high scoring hives, and repeat the process the following year. That addresses question 3.

Now the problem: nearly all the participants were too busy to actually test their colonies. What I have to report are the data from the 37 colonies that I tested and I can supplement that with communications with two other beekeepers that had incomplete data sets. So, rather than use this article to evaluate UBeeO effectiveness in regular beekeepers’ hands, I think it will be more useful as an example of the difficulty in drawing hard conclusions from experiments.

Figure 1: Preparing to treat with UBeeO. Hygienic behavior was scored by dividing the number of treated cells uncapped by the total number of cells treated. The treatment was applied within the PVC ring according to the instructions.

Figure 1 shows how the treatment is set up (sorry for the blur, it’s hard to keep your camera clean in the bee yard). Late-stage pupae are identified using a PVC ring. The pheromone is then applied within the ring and two hours later the number of treated cells that were uncapped were counted. The level of hygienic behavior was determined by dividing the number of uncapped cells by the total number of cells treated. Low activity is considered anything uncapping less than 40% of the treated cells. Medium activity is considered uncapping 40-59% of the treated cells. High activity is considered uncapping 60% or more of the treated cells.

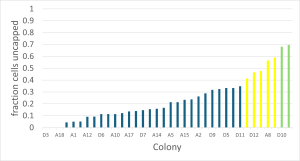

Figure 2: The frequency of hygienic activity detected in my tested colonies. 37 colonies were treated with UBeeO according to instructions. The graph represents the hygienic activity of each colony, which is calculated by the number of cells uncapped divided by the number of colonies treated. High activity (shown in green) means 60%-100% of the treated cells were uncapped. Medium activity (shown in yellow) means 40%-59% of the treated cells were uncapped. Low activity (shown in blue) means less than 40% of the treated cells were uncapped.

Figure 2 (see next page) shows the hygienic scores for my 37 colonies. Out of 37 colonies, two (~5%) showed high hygienic activity (68% and 70%) , five (~14%) showed medium activity and the remaining 29 (~80%) colonies showed low activity. The conclusion is that the UBeeO-induced hygienic trait is not very prevalent in unselected populations, right? Not necessarily. Play the skeptic. How else could I have gotten these data? 1. These were two yards, 10 miles apart. Perhaps this is an isolated incident true only for a small region of the country? 2. Single beekeeper, perhaps I inadvertently select for non-hygienic behavior with my breeder queens? 3. Single applicator, perhaps I mis-applied the product or stored it improperly? This is why you need to have experiments repeated. Fortunately, two other participants tested with UBeeO. Their stories were the same. One reported zero positives out of eight hives, the other reported a couple positives out of 25 hives. Both also questioned whether they applied appropriately. The real conclusion? Don’t know.

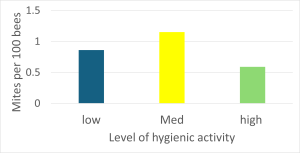

Figure 3: The average mite levels for all colonies showing a certain level of UBeeO-induced hygienic behavior. Those colonies showing high levels of activity are shown in green (n=2), those colonies showing medium levels of activity are shown in yellow (n=5) and those showing low levels of activity are shown in blue (n=29).

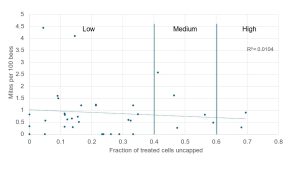

The second question was whether high UBeeO-induced hygienic activity correlated with low mite counts. There are several ways to look at the data. Figure 3 shows a bar graph of the average mite count per “class of hygienic behavior.” True, the high activity hives had lower mite counts than the low activity hives, but the medium activity hives had higher mite counts than the low activity hives. Statistically speaking, when you take into standard deviations, they are all about the same. Figure 4 shows a linear regression, which takes into account each hive. It comes out as a slightly negative slope with an R2 value of .01. That can be interpreted as a small negative correlation between activity and mite number. Hurray, right? Notice there are two hives with abnormally high mite counts (over four mites per 100 bees). They might be considered outliers. If you remove those two hives then you have a positive correlation between mite counts and hygienic behavior, also with an R2 value of .01. Given the small correlation either way, it’s fair to conclude there is no significant correlation between hygienic behavior and mite levels in your hive. Right? Well, for this data set that’s true, but are only two colonies with high levels of activity enough to really evaluate the question? What if those colonies had the same mite pressure as those two outliers, but due to their hygienic behavior they had half the number of mites? We just don’t know. You need lots of data points to be convincing.

Figure 4: Plot of mite levels vs hygienic activity looking for a correlation between activity and mite levels. Although the trendline shows a negative slope is it highly influenced by the two colonies with more than four mites per 100 bees. If those two colonies are removed, the trendline shows a positive slope. In THIS data set, there really is not correlation.

As you can see, it is difficult to draw convincing conclusions from a single experiment. Yet, it happens all the time. I wish I had a bigger data set to report to you. I wish I could tell you either way whether UBeeO is going to be a great breeding tool. But I can’t. Instead, I hope you take this as a lesson as to how complicated even simple experiments can be and why it is so important to have multiple studies before any real conclusions can be made.