Stephen Bishop

Well, I’ve done it. I’ve made a contribution to beekeeping science. I would like to thank everybody who has ever doubted my scientific and observational prowess, particularly my wife who is fond of calling me the world’s most unobservant person, for providing me the motivation to strive onward against all odds to reach scientific greatness. Mind you, I didn’t really make my discovery on purpose – I just kind of stumbled onto it–but isn’t that how most great scientific discoveries are made? I mean, Newton was just lazing about underneath a tree when an apple hit him on the noggin – and then, poof, theory of gravity. And, let’s face it, Fleming was kind of a slob who let mold grow on stuff – and then, poof, discovery of penicillin. And, thus, it happened to me. I discovered the world’s greatest pollinator plot completely by accident.

In fact, I was earnestly trying to avoid any discovery because the longer I live, the more anti-discovery I become. Discoveries are synonymous with bad and usually a downward trajectory in my bank account (for example, see the discovery of the leak in my roof).

Anyway, one day I was driving down the road, eyes straight ahead, diligently trying not to discover anything when I noticed something shadowy in my periphery. “Good gosh,” I thought, “what now?” I tried to resist, but my willpower failed me once again: I turned my head to look. “Holy smokes,” I said, “my whole field is black.” If only I hadn’t looked, my crop would still be green and vigorously growing like it had been days earlier.

(Disclaimer: most of what I write should be taken with a big block of red mineral salt, but you can absolutely trust the following bit of farming advice: if your crop suddenly turns black, something is wrong, bad wrong.)

I had planted a few acres of “milo,” which is what southerners call grain sorghum. Now milo is not something you would generally associate with an outstanding pollinator plant. Milo is in the grass family, so it doesn’t really target insect pollinators. But it does produce seed heads which can be harvested for animal feed. My plan was to harvest the milo with an old combine and run it through an even older hammer mill with oats and barley to create a complete and fulfilling ration for my pigs. Then someday in the future, I would sell sustainably-raised and overpriced pork to rich people in the city. That was the plan.

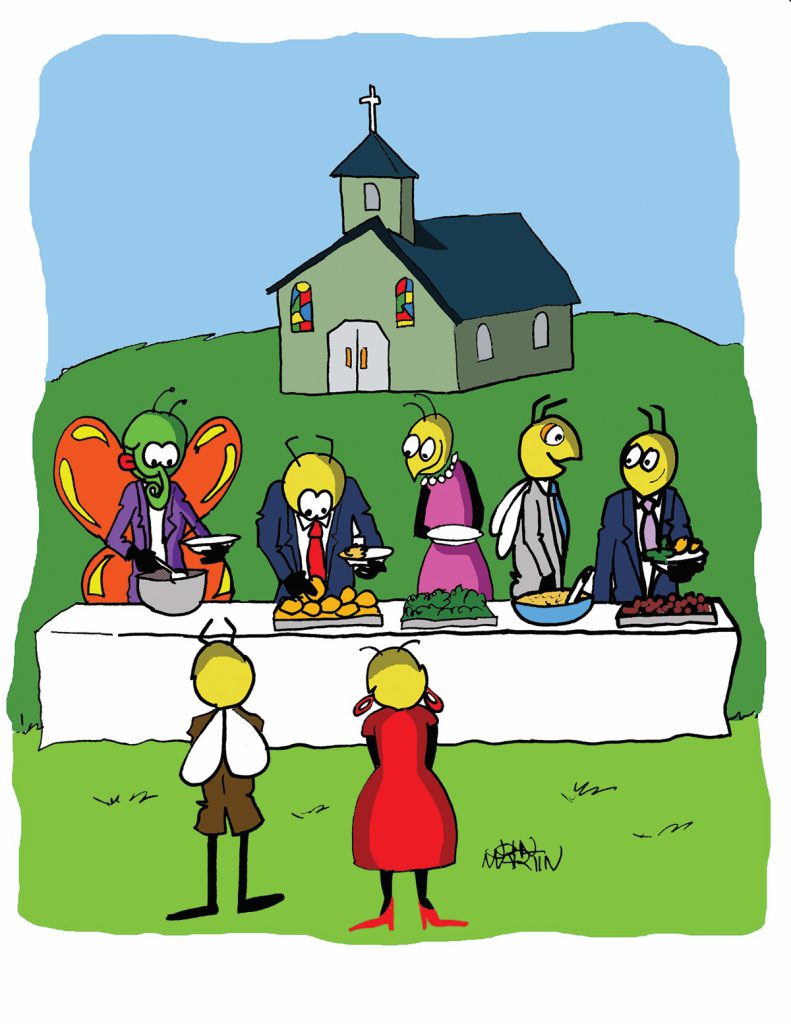

At least, that was the plan until I realized my crop was in the throes of death and I had yet again failed as a farmer. The problem was the sugarcane aphid. A few years prior, the aphid had expanded its palate from cane sorghum to grain sorghum and had become a major pest of milo in the south. As evidenced by my field, the aphid had now reached the foothills of North Carolina. The black color was from mold on the honeydew. Also feasting on the honeydew was a bazillion insects. I’ve never seen anything like it, and I’ve planted lots of pollinator/food plots over the years. Buckwheat, crimson clover, sunflowers, high-dollar wildflower mixes – nothing compared to what I saw in that ruined milo field. It was like the whole insect kingdom had descended to slurp up honeydew. Truly, I wish I had the entomological identification skills to describe what I saw. But, being the son of a Baptist preacher, all I can say is it was a giant congregation of six-legged species feasting like Baptists on homecoming Sunday.

Admittedly, it was a one-off, or what scientists would classify as an anecdotal observation. Strangely, I’ve never felt the need to replicate my farming failure, but if anyone else would like to try it, I will briefly summarize my scientific procedure for others to test.

Step 1: Plant milo in the southern United States.

Step 2: Spend a lot of money on fertilizer. Fertilize milo.

Step 3: Watch field grow green and healthy.

Step 4: Ride by field one day and notice field is suddenly black.

Step 5: Weep, cuss, and bemoan your luck. Second guess life choices.

Step 6: Inspect field and notice a bazillion insects feasting on honeydew.

That’s it. It should be a pretty simple experiment to replicate, but if you need more specifics, feel free to contact me and I can tell you which particular cuss words to utter and in what particular order to utter them.

Stephen Bishop lives in Shelby, NC. You can follow more of his farming failures at misfitfarmer.com