Rosamund Portus, research fellow at UWE Bristol

Originally printed in BeeCraft

There are few practitioners of bee husbandry who will easily forget the events which began to unfold in 2006. It was in November of that year when, according to Alison Benjamin and Brian McCallum (2009), beekeeper David Hackenberg visited his apiary only to find half of his hives empty, seemingly devoid of life. This discovery would come to be known as the first confirmed case of colony collapse disorder (CCD), a disorder which caused honey bees to disappear from their hives. It captivated the attention of people far beyond the usual scientific, beekeeping or agricultural communities.

Over a decade after David Hackenberg’s shocking discovery, I began a PhD project examining the decline of bee species. It was during this process that I became intrigued by how the crisis of CCD captured our collective imagination and brought the human and honey bee relationship under global scrutiny. My subsequent research demonstrated how the unique circumstances surrounding CCD resulted in the crisis being framed as an ‘ecological whodunnit’ (see Portus, 2020). My work, outlined in this article, traces the story of CCD, and provides an understanding of how the repercussions of CCD being framed as an ecological whodunnit continue to this day.

Following David Hackenberg’s devastating news of his empty hives, similar instances of honey bee loss were soon reported by beekeepers across the United States and, less prominently, in Europe (Oldroyd, 2007; Dainat et al, 2012; Cressey, 2014). But with few physical honey bee remains to study and no clear presence of any specific disease, pathogen or parasite, the reason for this sudden disappearance left researchers puzzled (Watanabe, 2008).

As expected, the sudden disappearance of honey bees inspired significant media attention. In an article in The Guardian, John Vidal (2007) described CCD as a “mystery plague.” In the same article, Vidal quoted a London-based beekeeper who compared the crisis to the case of the Mary Celeste, a ship from which the crew famously and mysteriously disappeared. In a similar tone, Alexei Barrionuevo (2007) wrote in The New York Times how “in a mystery worthy of Agatha Christie, bees are flying off in search of pollen and nectar and simply never returning to their colonies. And nobody knows why.” Finlo Rohrer’s (2008) article for BBC News Online likewise emphasised the ‘thrilling’ nature of CCD, suggesting that future beehives would stand empty, their “once-buzzing occupants mysteriously vanished.”

As time moved on, the culprit behind CCD continued to prove elusive which, as described by Lisa Moore and Mary Kosut (2013), resulted in people imagining all manner of reasons for honey bees’ disappearance: “Did they leave purposefully – simply walk off the job? Were they forced out of their hives?” Yet, rather than dampen people’s interest, the continued lack of a definable ‘killer’ only served to intensify CCD as a dramatic and fear-inducing whodunnit story. The New York Times continued to describe CCD as “one of the great murder mysteries of the garden” (Johnson, 2010), National Geographic labelled it a “mysterious killer condition” (Holland, 2013) and Science News ran the headline, “Honeybee Death Mystery Deepens” (Emerson, 2010). Throughout the past decade concerns surrounding CCD began to circulate in ever-widening forms of media communication, with the 2010s seeing the release of feature-length documentaries1, TED Talks2 and publications of both nonfiction and fiction works3.

In the present day, as cases of CCD dwindle, it has become generally agreed that a multiplicity of factors is responsible for the disorder (Milius, 2018). Indeed, public interest surrounding the mystery has all but vanished. Yet, the legacy of this ecological whodunnit remains. The intrigue which accompanied this narrative propelled the plight of both domesticated and wild bee species onto a global platform, cementing their struggle as one of the key environmental concerns of our time.

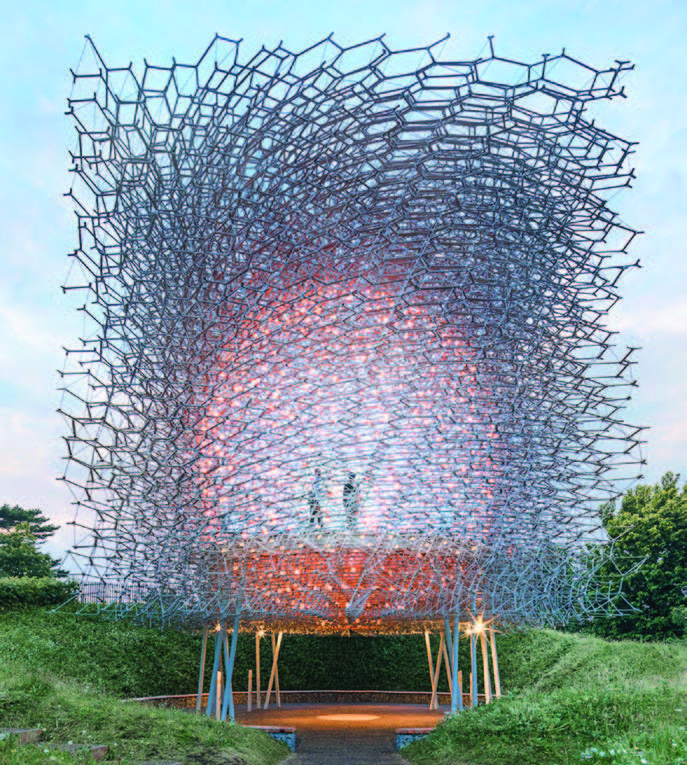

The centrality of bees’ plight in environmental thinking is captured well by the results of a 2014 YouGov poll which surveyed adults living in the United Kingdom. It found that people felt bee decline was more urgent than climate change (Dahlgreen, 2014). Today, this sense of urgency and anxiety for bees, which has extended itself even to places where bee loss has yet to be witnessed continues to show itself through bees’ apparent adoption as mascots of extinction (Phillips, 2020). Examples include the blazoning of bees’ image across the flags of Extinction Rebellion protestors (Portus, 2020), the installation of creative works examining bees’ plight in places such as Kew Gardens (Benjamin, 2016) or, despite their questionable success, the inclusion of bee boxes into the walls of every new house developed by Brighton and Hove City Council (Booker-Lewis, 2020; Marsh, 2022).

The framing of honey bees as victims in this whodunnit invited audiences to see them as real, sentient and suffering creatures which, in turn, developed people’s curiosity and empathy for these other lives. It is critical to recognise that the pain caused by CCD, and bee loss more widely, is devastating and deeply felt by many people and for myriad reasons. My exploration of how the stories surrounding CCD framed the crisis as a collective ecological whodunnit does not bypass recognition of the pain caused by CCD, but rather acknowledges that from the darkness of this circumstance came the opportunity for people from all walks of life to expand their knowledge of, and care for, the human-bee connection.

At the birth of a media phenomenon Jerry Hayes, editor of U.S. magazine Bee Culture, told BeeCraft about his part in the discovery and naming of colony collapse disorder. “In 2006, when I was chief of the apiary section of the Florida Department of Agriculture, I had a call from a commercial beekeeper called David Hackenberg. He said his bees were disappearing – not dying but just disappearing. I went along and he was right. His bees weren’t dying, they weren’t swarming, they weren’t absconding – they were just gone. Usually there were only a few bees and the queen left behind in a demoralised condition. I started contacting colleagues in other states and they said they were seeing the same thing. I remember sitting on the floor at 10:30pm talking to folks on the phone and none of us knew what was going on, but we knew it was really significant. We knew the media were going to get hold of the story and that we’d better give the phenomenon some kind of name. So, we came up with the term colony collapse disorder – CCD. We knew from many years’ experience that the media didn’t ever pay attention to bees or beekeeping and that the story would soon go away. But it didn’t. The media went crazy and latched onto CCD and the idea of bees as the canary in the coal mine and that the environment was doomed. The story ran and ran and ran. Many people wanting to save the world took up beekeeping as a result and sometimes their bees died too – but this time usually because they didn’t feed them or treat them for varroa. But CCD was always at fault. I came to wish we hadn’t come up with the term CCD because it became the excuse irresponsible beekeepers used when they didn’t want to take the blame.”

For a full write up of this research, please see my longer publication on this subject: Portus, R. (2020). An Ecological Whodunit: The Story of Colony Collapse Disorder. Society & Animals. 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685306-BJA10026.

FOOTNOTES

1 Documentary titles include Colony (2009), Vanishing of the Bees (2009), Queen of the Sun: What Are the Bees Telling Us? (2010), More Than Honey (2012) and The Pollinators (2019).

2 Relevant TED Talks are A plea for bees (vanEngelsdorp, 2008), Every city needs healthy bees (Wilson-Rich, 2012), Why Bees Are Disappearing (Spivak, 2013),and The Case of the Vanishing Bees (Bryce, 2014).

3 Non-fiction works include The Beekeepers Lament: How One Man and Half a Billion Honey Bees Help Feed America (Nordhaus, 2011) and A World Without Bees: The Mysterious Decline of the Honeybee – and What It Means for Us (Benjamin & McCallum, 2009). Fictional works include The History of Bees (Lunde, 2015) and The Bees (Paull, 2014).

REFERENCES

See tinyurl.com/BC2022-05-07

Dr Rosamund Portus, research fellow at Bristol UWE, works in the field of the environmental humanities. Her current research examines young people’s experiences of climate emergency and climate education. Her PhD considered creative and cultural dimensions of bee decline. She is also an artist.