Click Here if you listened. We’d love to know what you think. There is even a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

The Honey Bee’s Winter Nest

The Honey Bee’s Winter Nest

Necessary for Surviving the Big Dearth

By: James E. Tew

But first, these thoughts

Over time, beekeepers change their ways, but bees always stay the same. During the past few years some novel issues, that are new to beekeepers, have been suggested and discussed in the media. Whether or not bees sleep has been addressed and then re-addressed. Apparently, they do. If bees feel pain or have other sentient qualities have been topics of other discussions. These unclear bee qualities are still being explored. Even honey is in the bright light of the popular media. Some postulate that bees are not the only animal able to make a honey-like product. Somewhat like lab-grown protein, a sweet product, having chemistry akin to that of honey, has been blended with nary a bee in sight. Is it honey or not? Topics like this help keep beekeeping interesting and keep bee knowledge evolving.

These are not the bees’ problems

All these current discussion topics are beekeeper related. While we humans gnash and pontificate, the bees plod along in their own world doing their own thing. Their biology is consistently their business and honey bees seemingly worry not one whit about their human counterparts. It appears that the beekeeper/bee relationship is totally one-sided one.

Figure 1. The moment of interaction between two distinct species – humans and bees.

Bees’ complex and mysterious biology

Though topics abound, it seems to me that our most recent significant advances in understanding our bees has been in the areas of bee biology and related pathogenic subjects. While we know much more about our bees today, we still are far from understanding everything.

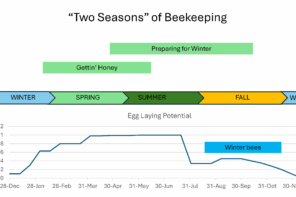

Preparing for foodless times

In a real way, much of what bees do in the Springtime is in preparation for the next Winter season. To survive Winter’s coldness, bees must find a suitable nest site and construct combs, which are their only nest furnishings. They must gather food and store it. They must maintain a queen presence, maintain worker populations and swarm to procreate their species. They must defend their nest from interlopers and even defend against their own marauding bee neighbors. Without a protected nest site and suitable stocks of food, a honey bee nest will surely die in the Winter season. Bees clearly understand this harsh fact. Their base of operations – the nest – is critical to withstanding the Winter season.

Figure 2. What a honey bee nest looks like without beekeeper involvement. Note the propolis band around the combs.

The natural nest – an absolute necessity

When searching for a home, bee scouts usually look for a surprisingly small cavity – maybe as small as one cubic foot (.023 cubic meter). Finer features of a future home are that it should: be dark, have a defendable entrance, be dry and not have anything else living there such as birds, squirrels or ants. Ideally, it should not be on or at ground level.

When tearing into trees, early beekeepers were confronted with a morass of bees, comb, brood and dripping honey. How could any rational organization be seen in such chaos? As we now partially understand, the bee nest is a highly structured living environment. Understanding that fundamental structure – so much as is currently possible – can help make all of us better beekeepers.

The size of the nest

Feral nest sizes seem to vary significantly. How quickly, if ever, a colony can fill a cavity varies greatly; therefore, some nests are large while others stay relatively small. Reasons for size variations could be genetics, diseases, pests and water. The availability of nectar and pollen resources is critical. Simple, blind luck is also a helpful characteristic to a feral colony.

In fact, as humans have altered the general environment, suitable nesting sites have become much dearer to scouting bees forcing them to accept sites not perfect for their needs. Occasionally, a swarm is forced to build in the open, a fatal decision for most nests within the temperate parts of the U.S.

The nest fixtures

The natural bee nest is plainly furnished with wax combs only. Though bees can diligently modify the nest cavity to a degree, for the most part they must accept the space as it is. Along the top and sides of the nest, surveyor bees will lay out the beginning midrib of combs and other bees will begin to construct comb along those lines. We don’t know how these bees measure the spacing needed when establishing dimensions for future comb. Keenly observant beekeepers long ago discovered that bees require a specific living and working space – or the famous bee space concept. That understanding allowed the subsequent development of artificial domiciles that we have used for more than one-hundred years.

When bees first occupy a new nest cavity, the first matter of business is to construct worker combs. Besides being an area to nurse developing worker bees, worker-sized comb can also be used to store nectar, pollen and occasionally water.

Comb construction

To us, new combs seem to be produced almost mystically. The bees will mass together into a group that we have called a cluster. The cluster is not a rigid structure but is fragile and temporary. As bees hang together in such a cluster, gravitational forces will cause it to hang perpendicular with that influence. In essence, combs are built at right angles with gravity’s pull. Later, within the dark hive, this gravitational orientation becomes important in the dance language communication procedure.

Four pairs of wax glands on the ventral surface of the bees’ abdomen produce snow white wax flakes. Comb constructing bees pass a newly produced wax flake forward to their mouths where the wax is chewed and pulverized. After a short time, the wax particle is molded, using the bees’ trowel-shaped mandibles, into a cylindrical developing cell. It’s a communal effort. Other bees may reshape previous efforts before adding their own contribution of wax to the new cell, but finally a new cell is produced. No single bee actually constructs a single cell.

Experienced beekeepers have seen the completed cells in use near the top of a new frame while lower on the comb, shallower cells will still be under construction. Bees build comb as needed. New wax melts down to canary yellow and is valuable for candles and other wax-produced products. It’s a beautiful product.

The importance of a nectar flow

Inexperienced beekeepers are frequently disappointed that all brood chamber space and super space is not used by the bees during a particular season. Indeed, beekeeper-supplied foundation may even be chewed and mangled by bees, and not building comb on it (though it will probably be successfully used during subsequent seasons).

Bees will only construct comb on the impetus of a nectar flow and a comb space shortage. Simply stated, bees must have construction material (nectar) before they can build. Nectar provides that building material, but an unusual building material it is for it can also be stored as honey rather than restructured into wax. Bees will not use stored honey to construct significant amounts of new comb. The experienced beekeeper will provide previously drawn comb for the bees to store the honey crop rather than requiring bees to rebuild comb each year.

Comb is costly for the bees to build. It has been found that bees must metabolize about seven to eight pounds of honey to produce one pound of wax. But with that one pound of building material, bees can build 35,000 cells in which they can store 22 pounds of honey. Consequently, their approximate net gain after consuming eight pounds of honey is 14 pounds of stored honey plus reusable comb.

It takes about 10,000 bees, over a three-day period to produce one pound of wax. That one pound will be made up of about 500,000 scales. Comb construction for the bee hive is clearly an investment. Inexplicably, cappings and other wax particles are not reused to any degree but are allowed to drop to the bottom board where they either accumulate or are discarded in front of the colony. New wax is soft and pliable and will break easily, but as the comb ages, it becomes reinforced with cocoons and propolis. Whereas new comb is snow white, old comb is nearly jet black.

Figure 3. New and old comb comparison.

Types of comb cells within the beehive

Worker comb is, by far, the most abundant comb size within the colony. As mentioned previously, worker sized comb (about five cells per inch) can be used by bees to house developing worker bees or to store honey and pollen. Larger cells, about four per inch, are used to produce drone larvae or to store honey and pollen.

Distorted cells or cells of intermediate size can occur that are used by bees to splice comb cells together. In other words, worker comb will be filled with patches of drone comb with small amounts of transitional comb wherever needed in order to make a piece of solid comb. Some cells may either be drastically modified or built purposefully for raising queens. As you would expect, this type of comb cell, though distinctive is not very common within the combs. A precursor to queen cells are queen cups which are simply queen cells that are not in use. Worker cells, drone cells, queen cells and transitional make up the types of comb cells within the colony.

Figure 4. Common burr combs on top of frames. This is a common sight for beekeepers. Note bee space separating frames.

Brace comb, burr comb or ladder comb

Bees will frequently build brace comb between frames, above or below frames, or on the bottom board – especially after a colony has been recently moved. Anywhere bee space is violated, additional comb may be built that is a nuisance to beekeepers in commercially manufactured hives. Normally, in managed hives, it is scraped off and melted as high-quality wax. Within wild nests, it remains in place and helps give rigidity to the overall nest.

Bee space

The concept of bee space has been mentioned several times. Within both wild and managed hives, bee spacing must be respected. Bee space is generally considered to be anything between ¼” and ⅜”. Space less than ¼” will be filled with propolis while anything greater than ⅜” will have either comb or brace comb built within the space depending on its size. In our beekeeping literature, the Reverend L.L. Langstroth is generally given credit for conceptualizing the notion of bee space.

Propolis – the colony’s caulking compound

Propolis is little known outside of the inner circles of beekeeping. Produced from resinous materials collected from the buds of trees or from resins from softwoods, propolis is used to caulk the hive tight. Though stringy and sticky when fresh, propolis dries hard and brittle. It is soluble in alcohol and has a pleasant weedy odor.

Since there is no real difference between the two, both wild and managed bees produce propolis. Caucasian bees are renowned for collecting copious amounts of propolis and will occasionally nearly close an entire colony entrance if left to their own schemes.

Propolis is the material that causes the hive to crack sharply when opened. Propolis was the primary demon that relegated so many hive designs to beekeeping’s junk heap. If colonies are not opened for several years, propolis will make the hive very nearly impenetrable. Propolis, along with pollen, darken white wax over a period of just a few years. Additionally, in addition to being used to polish cells, propolis is added to the wax that covers cappings; therefore, giving them a different appearance than honey cappings.

Propolis is bacterially active and will restrict bacterial growth. Probably due to this antimicrobial characteristic, propolis is used to entomb anything the bees can’t move – such as a dead mouse or a small tree twig.

There it is – the dark nest

Inside this dark maze of twisted, bee-spaced combs the bees live in hot, humid darkness during warm months and cold darkness during Winter months. Through the beekeeping years, innovative beekeepers have learned how to take the bees’ penchant for building natural comb and have enticed them to build comb within wooden frames – mainly for our human convenience. It’s too difficult to remove cross-combed frames for honey removal, disease inspection or colony manipulations.

Inside the warm, dark nest

Inside the warm, dark nest, bees probably communicate by pheromone perception (crudely described as a type of odor), touch and other sensory perceptions such as gravitational sensitivity and electro-magnetism.

The nest is incredibly crowded. Bees are literally shoulder to shoulder. Yet, all these characteristics vanish when the beekeeper removes the outer cover from the hive. All becomes visible and the normal way of the colony, with the application of smoke to mask the effective communicative odors, is disrupted.

Within the undisturbed dark hive, everything has a unique odor: workers, the queen, drones, nectar, wax moths, brood, pollen, the hunger of larvae, danger, whether larvae are in the correct cell – everything seems to have an odor cue (or some other kind of indicator) within the dark hive. As beekeepers, we crudely use smoke to mask this elegant chemical communication.

Temperature must be regulated to about 95°F in the brood nest, nectar must be enzymatically reduced and excess water removed to form honey, brood must be fed freshly collected pollen and this hive-city must be defended from intruders and pests.

This society must be kept in balance. In a full-strength colony, there are about 60,000 reproductively sterile workers, one fertile queen and about 400-600 drones. Developing brood must be produced in anticipation of upcoming nectar flows or Winter seasons. All these individuals come together to form the super-organism – the bee nest. Even under ideal conditions, individual bees are incapable of supporting themselves for more than a few weeks. The total bee nest is the animal – not the individual bee. Such is life in the bee’s nest – so much as we can understand.

Dr. James E. Tew

Dr. James E. Tew

Emeritus Faculty, Entomology

The Ohio State University

tewbee2@gmail.com

Co-Host, Honey Bee Obscura Podcast

www.honeybeeobscura.com