By: Miles Sarvis-Wilburn

The word dystopia is the antonym of utopia, the latter commonly thought of as an ideal place or good imaginary world.

Yet utopia has far more interesting linguistic roots, as it was coined by Thomas More in 1516 and reaches back from Modern Latin “nowhere” to the Greek ou “not” and topos “place.” Linguistically speaking, the fundamental characteristic of a utopia is not its supreme goodness or idealism, rather, it is the fact that it does not and perhaps cannot exist. Dystopia takes a different turn; most notably used by John Stuart Mill in 1868, it means “imaginary bad place” and thus places a distinct normative judgement upon the item at hand.

It took 352 years for utopia to lead to dystopia, and another 181 years to reach the imaginative setting of Blade Runner 2049. Honey bees and their keepers were very busy over this period of time. Shortly after the publication of More’s Utopia, the first European honey bees were imported by the Spanish to South America. At this time moveable frames had not yet been invented and we still believed bees gathered honey directly from flowers. But beekeepers are a creative bunch and were actively moving into new forms of beekeeping. These experimentations culminated with the publication of Lorenzo Langstroth’s seminal work The Hive and the Honey-bee in 1853, a mere fifteen years before the term dystopia is widely introduced by Mill. Since then, the Langstroth hive has become the most commonly used hive in the world and countless dystopian works have been created. How many of these feature honey bees? That is a question beyond the scope of this piece which will look at one work in particular: the film Blade Runner 2049, released in October of 2017.

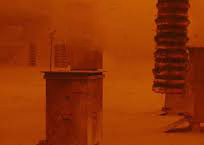

Amidst the ambient booms of the soundtrack and the vast landscapes panning across the screen, only a beekeeper would pay special attention to the bees in Blade Runner 2049. We meet them but briefly – two thirds of the way through the film – while “K” (Ryan Gosling) is searching for “Deckard” (Harrison Ford) in a desert of haze and crumbling monuments. The terrain is bleak and K wanders until surprised by a single honey bee that has landed on his hand. Himself a bioengineered human known as a ‘replicant,’ we can safely assume he has never seen a real bee before. He stares blankly for a moment until she leaves him, then follows her bee-line to a small apiary of just under 10 Langstroth hives, many of which bear multiple supers. The buzzing of the colonies is perhaps the first animal sound in the entire film. Entranced, K calmly slides his hand into the entryway of one of the hives and the bees beard onto his skin like a glove. He leaves the apiary then, this scene taking no more than a minute and a half, to return to his quest.

We must assume Deckard set up and operates the apiary. Deckard with his loving dog and collection of vintage items, living alone in the dystopian hell that surrounds him, it is he who has been humanized to the viewer of an un-human world. Is it a human thing to keep bees in the desert? There is no forage for them in the immediate area, nor perhaps anywhere on the planet as even the industrial crops have been secluded and automated. Instead, they feed from disc feeders suspended like rigid accordions playing no notes. The sugar substance within is likely genetically modified in a fashion we cannot understand – recall that in this world replicants are birthed by falling out of plastic embryonic sacks. Yet these consequences and conditions are irrelevant to the bees. They continue as they always have, with what they have, to survive. Like Deckard they are a world within a world, a small piece of what once was.

When we look at the situation of the bees more closely we realize that the mechanisms used to humanize Deckard only contribute further to his isolation. His collection of records, booze, and furniture show how he is like us, human, but these things are in and of themselves only links to the past. They are real within an irreality and fading fast. Even if Deckard should return with his daughter and live happily ever after, they will always be living like the bees: stripped of a nuanced existence. If a utopia is a not-world and dystopia a bad not-world, the latter could be described as world wherein there are only portions of life, useful for this and used for that but always incomplete. In the world of Blade Runner 2049 the bees are such; they are akin to a human being on life support. They receive only the bare minimum of nutrients and complexity, just enough to allow them to keep moving, building comb, and filling cells with what once was called honey.

The film inadvertently asks of us a simple question: what are bees without flowers? When we ask this question we begin to look at the practice of beekeeping differently. A world opens up from the bees themselves to the sources of nectar and pollen they need to survive, to the topsoil in which these flowers take root, and finally to the watershed that supports everything growing. We begin to think about how Deckard technically is beekeeping but his is a hollow form lacking vitality and beauty. It exists like a decomposing corpse wherein we can see and know what it was, but do not wish to look too long. Without flowers bees are lost – literally, they have nowhere to go. In this dystopia they have no reason to exist and we do not give them one. Instead, we functionalize their being and inadvertently turn them into living ghosts. We perceive their taking sugar water and making half-real honey as well-being, and congratulate ourselves on having fixed a problem we created. Only they are not there, not really.

The film inadvertently asks of us a simple question: what are bees without flowers? When we ask this question we begin to look at the practice of beekeeping differently. A world opens up from the bees themselves to the sources of nectar and pollen they need to survive, to the topsoil in which these flowers take root, and finally to the watershed that supports everything growing. We begin to think about how Deckard technically is beekeeping but his is a hollow form lacking vitality and beauty. It exists like a decomposing corpse wherein we can see and know what it was, but do not wish to look too long. Without flowers bees are lost – literally, they have nowhere to go. In this dystopia they have no reason to exist and we do not give them one. Instead, we functionalize their being and inadvertently turn them into living ghosts. We perceive their taking sugar water and making half-real honey as well-being, and congratulate ourselves on having fixed a problem we created. Only they are not there, not really.

Deckard’s bees are replicants of a different form. They are a shell of their long history, a history much deeper than that of human beings, and one that will inevitably come to a silent end. When the colonies outside of Deckard’s desert home die they will not be noticed as they were never truly alive. They will become like the other large-scale imagery in the film, testimony to a world long gone and untouchable. The true dystopia of Blade Runner 2049 is not the inhumane world of replicants nor the destitute poverty of human beings, though these are terrible indeed. Rather, the bad not-world is quite literally a world that is incomplete. This is a world without flowering life and strewn with brief buzzing sepulchers filled like catacombs of pollinators drifting.