Click Here if you listened. We’d love to know what you think. There is even a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

The Brave New World of Beekeeping Created By Our Climate Emergency Part 2

By: Ross Conrad

Last month in Part I of this article, we looked at the impacts the growing climate crisis is having on honey bees and the beekeeping industry. This month we’ll explore some of the things beekeepers might be able to do to limit the damage and harm the growing climate crisis is inflicting upon our industry. The following can be thought of as the start of a beekeepers’ climate response toolbox which should start with the cultivation of flexibility, resourcefulness and resiliency.

Flexibility

In order to survive the growing crisis, we are going to have to be flexible. This means being willing to let go of long held past beliefs and actions when appropriate and not always automatically proceeding as we might have previously. Hive manipulations will need to become based on local weather and geographical conditions, and the status of plant development in the region rather than by the calendar. Beekeepers are also going to have to get used to the idea that some of the things they are used to doing will have to be abandoned and new approaches will need to be adopted if we are to have a chance of successfully navigating our destabilized climate.

Resourcefulness

We have no choice but to do all we can to stay on top of the rapidly changing world around us. The more sources of accurate information, ideas and management options, the faster we will be able to adjust to overcome challenges and difficulties.

Resiliency

We will all want to build as much resiliency into our beekeeping as we can by having back up plans for all critical systems in our operations. Such things as having a backup power source or access to manual tools and equipment should electricity become unavailable, is a good place to start. Cultivating additional sources for critical inputs like bees, queens, honey jars, labels, treatments and woodenware can make the difference between being able to stay in business or having to close up shop.

Handling heat

Colonies need to maintain a temperature between 93-95°F (34-35°C) in the brood nest. As the planet continues to heat up, we beekeepers will have to pay greater attention to preventing hives from overheating. Ventilation is one of the easiest ways to help cool honey bee colonies. Whether it’s an upper entrance, an open screened bottom board, a solar powered hive ventilator, or simply lifting the outer cover and moving it back a little so the front edge rests on the lip of the inner cover and allows air to flow out the top of the hive, increased ventilation provides relief for colonies on hot days.

Painting hives white and using wooden migratory style outer covers instead of metal clad telescoping covers that heat up in the sun also help. When possible, planning apiary locations so hives are shaded from the sun, especially during the afternoon which is typically the warmest time of day, will go a long way in prevent colonies from overheating even in the hottest locations.

Excessive heat in Summer is not the only threat of rapidly rising global temperatures, we can also expect Winters to be warmer than they have been historically. We know that when a queen’s egg laying and a colony’s brood production proceeds through the entire Winter, the additional nutritional requirements are considerable. Beekeepers used to managing colonies that shut down their brood production to conserve food during Winter will have to adjust. This means that when preparing colonies for Winter, the amount of supplemental food provided by the beekeeper to address these new conditions and prevent starvation will have to be modified. Without regular Winter monitoring during this transition, beekeepers are unlikely to be aware of this change in their colony’s overwintering needs until food reserves are depleted and the bees are dead.

Honey bee colonies have proven their ability to survive when temperatures reach well above 100°F (38°C) as long as they can collect water and spread it throughout the hive to harness the cooling action of evaporation. Making sure colonies have access to water throughout the year will support the bee’s natural instincts for self-help in keeping their hive comfortable when temperatures soar.

Dealing with drought

Ensuring adequate water access for bees will alleviate the colonies water needs during drought conditions. Unfortunately, there is typically little beekeepers can do to address the water requirements of the plants the bees rely on for food. Without adequate rain, plants often do not have access to enough moisture in the ground to produce nectar. Drought can also cause the quality of the pollen plants produce to decreases significantly (Arathi and Smith, 2023).

Beekeepers have grown accustomed to feeding colonies sugar in order to make up for a lack of nectar. Unfortunately, human carbohydrate feeding of honey bees is not associated with strong and healthy bee immune response which can result in increased vulnerability to hive diseases. (Taylor et. al., 2019)

Rather that have to feed an artificial diet on a regular basis, beekeepers in areas experiencing severe water scarcity might have to consider moving apiaries to wetter locations where natural forage is more abundant. Moving colonies out of drought areas mimics what African bees naturally do during the dry season.

The degradation of pollen during drought conditions combined with the lowering of pollen’s protein content from the increased atmospheric CO2 may well mean that the regular supplemental feeding of protein to honey bee colonies will become a standard hive management practice in the future. This will present additional challenges for beekeepers working in northern areas as long as temperatures continue to allow colonies to continue to go dormant during Winter. Northern beekeepers will have to be sure any protein supplements they use support beneficial bacterial growth and fermentation. Otherwise, the bees won’t be able to preserve the supplemental protein in the hive like they do with natural pollen. Failure to attend to this detail may result in serious nutritional deficiencies and lead to an increase in weak and dead colonies come Spring.

Confronting fire

Another hazard association with drought conditions is the threat of wildfire. The best the beekeeper can do to mitigate this hazard is to keep apiaries and their immediate surrounding areas free from as much vegetation and other flammable fuel sources as possible. One way to accomplish this is by situating apiaries on old concrete foundations and keeping surrounding vegetation trimmed and cleared away.

Even more difficult is adjusting to the hazardous air quality caused by the smoke from wildfires. This danger can make things especially difficult for beekeeper health while working outside in the bee yard, and make it downright impossible for those with asthma or other respiratory challenges to tend their colonies.

Facing floods

Increased extreme precipitation events and storm surges are predicted for many areas, especially the Northeastern United States. To address the threat of flood waters, keep apiaries well away from sources of surface water or up on high ground. Securely anchored elevated hive stands can be a good stand in for locations where avoidance and high ground are not possible.

Weathering winds

Stronger tropical storms along with typhoons, tornados, hurricanes and cyclones can lead to devastating wind damage. While not much can be done to survive unscathed from the direct hit of a severe wind event such as a twister, preparations can be made that can reduce the level of damage sustained from less severe winds. This includes providing sturdy and durable wind breaks, securing outer covers, and anchoring hives down in some way. Apiaries positioned in open clearings are preferred since those situated near large trees have the increased risk of being damaged by uprooted, broken and falling trees and limbs.

Unintended consequences

The warming climate can also be expected to disrupt the ability of plants to be able to attract pollinators. Certain plants have developed the ability to heat themselves up so the aromatic compounds in their nectar and pollen are given off in greater concentrations in order to help attract more bees and pollinators. This evolutionary development allows these plants to compete against all the other plants that are also seeking pollinator services. Unfortunately, this unique approach to attracting pollinators is threatened when the number of days when temperatures are cool decrease, negating the advantage of botanical thermogenesis (Seymour and Matthews, 2006; Podorvanov, 2014; Dieringer et al., 2014).

Infrastructure threats

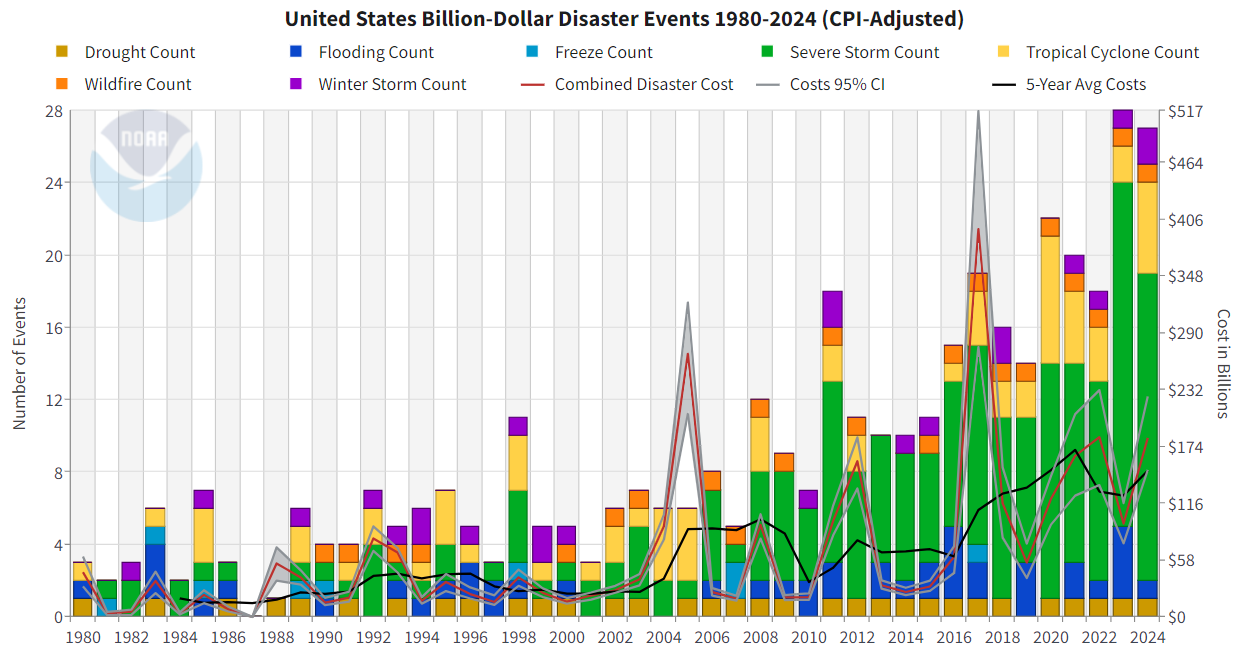

Honey production facilities are often vulnerable to fire and wind damage. Meanwhile floods can not only destroy a honey house, but can tear up access roads and bridges, destroy farmers’ fields and wipe out crops, prevent the shipment and delivery of goods, overrun our water treatment plants, and on and on and on. There are other areas of related concern, too numerous to describe here. The total costs imposed on society for all this, including medical expenses, are going through the roof.

While insurance can help, the dramatic increase in the cost of insurance claims in the past decade is causing many insurance companies to greatly increase their rates and even stop providing coverage altogether in the most disaster prone areas. If we continue to burn fossil fuels, the economic costs to all of us will be beyond staggering.

The spiral of climate silence

In an effort to preserve their profits for as long as possible, fossil fuel industry lobbying and influence has convinced various organizations and government entities to ban their employees from talking about the problem. Many have even gone so far as to ban the use of the words ‘climate change’ and ‘global warming’ in speech, print and websites. This is part of industries effort to delay societal action designed to address our worsening situation. If people (and their representatives) don’t hear anyone talking about the issue, they tend to assume that it is not as bad as they think it is. Therefore, they don’t talk about it either and policy makers don’t hear people’s concerns so they give the issue low priority. This prevents progress on solutions, which leads to the climate crisis getting worse.

Adaptation

Meanwhile, many political and media personalities claim that we will just adapt to the “new reality” of our situation. Such reassurances are false, misleading and ultimately extremely dangerous as they can lull us into thinking that we can simply adjust and live with the climate crisis.

Beekeepers understand that if they use the same synthetic chemical mite treatment every year, mites will quickly develop resistance to the treatment. To prevent the ability of mites to adapt and build resistance, it is important to use different chemical treatments throughout the season, or at least annually. Diversifying treatments keeps the internal hive environment chemically destabilized and constantly changing, making it extremely difficult, if not impossible, for the mites to develop resistance.

The same principle applies to our ability to adapt to a destabilized climate. Until, we stop adding significant amounts of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, the climate will not become stable enough for us to be able to actually adapt to a “new normal”. This is simply because until we stop burning fossil fuels, there is no “normal climate,” just a constantly changing one. The best we are going to be able to do is simply react to the latest disaster the best we can, hope to recover, and then pray we will have enough resources remaining to react and recover again to the next crisis, and so on. As beekeepers, we need to prepare as best we can to confront a much more chaotic and difficult future. That’s the view from the apiary.

References:

Arathi, H.S., Smith, T.J. (2023) Drought and temperature stresses impact pollen production and autonomous selfing in a California wildflower, Collinsia heterophylla, Biology and Evolution, pp 1-12, https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.10324

Dieringer, G., Cabrera, R.L., Mottaleb, M. (2014) Ecological relationship between floral thermogenesis and pollination in Nelumbl lutea (Nelumbonaceae), American Journal of Botany, 101(2): 357-364

Podorvanov V.V. (2014) Thermogenesis in plants, Ukrainian Botanical Journal, M.G. Kholodny Institute of Biology, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Kyiv, 71(1): 96-103

Seymour, R.S., Matthews, P.G.D. (2006) The Role of Thermogenesis in the Pollination Biology of the Amazon Waterlily Victoria amazonica, Annals of Botany, 98(6): 1129–1135, https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcl201

Taylor, M.A., Robertson, A.W., Biggs, P.J., Richards, K.K., Jones, D.F., Parker, S.G. (2019) The effect of carbohydrate sources: Sucrose, invert sugar and components of manuka honey, on core bacteria in the digestive tract of adult honey bees (Apis mellifera), PLOS ONE, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225845