Grumpy Swarm

Grumpy Swarm

From the Editor, Jerry Hayes

QUESTION

Early on, I was fortunate to discover that the myth that all swarms are gentle is a big myth. When one of my first colonies swarmed, my husband showed it to me in the hedge. I was dressed in the clothes I wore to teach, not my bee suit, but that didn’t stop me from trying to put the swarm in a box. Man, they nailed me! I got at least six, probably more, stings and ran into the house feeling my body pulsating! I never repeat that myth!

Etta Marie

Answer

Long, long ago on a planet far, far away after being a high school teacher, I went back to school to study my new passion, apiculture. My major professor was Dr. Jim Tew at the Ohio State University. I was a new beekeeper and wanted to immerse myself in everything Dr. Tew could share and demonstrate.

It was Springtime in Ohio. Dr. Tew got a call from campus security that there was a honey bee swarm on a short sign pole in the parking lot. He asked if I would like to learn how to collect it. “Of course,” I said. We went to the storage building and got a nuc box with a top and bottom and a bee brush and took this out to the parking lot where we found the swarm on the five foot T-post. Dr. Tew explained that we didn’t need any protective gear as swarms are gentle. As instructed by Dr. Tew, I took the frames out of the nuc box and placed it directly below where this fairly large swarm was hanging onto the T-post. For the next step, I was then told to hold the bee brush above the swarm and then in one motion smoothly move the brush down and ‘dislodge’ the swarm, making it fall into the nuc box. And voila we will have captured the swarm.

I did as instructed. Immediately, the swarm did not smoothly fall into the nuc box but instead went to my face and body along with Dr. Tew’s face and body. We ran. After this learning experience, Dr. Tew explained to me that most swarms fill up with nectar and honey so that they will have some resources to begin wax production at the new colony hive location and as such they are calm and because their abdomens are full of honey, they cannot bend their abdomens easily to insert their stingers in a threat. But, sometimes there are multiple swarms from a colony and not enough nectar/honey resources to fill up on before they leave. They are called ‘Dry Swarms’. So 40 years ago I learned about ‘Dry Swarms’ from the best.

Have a wonderful sting-free day!

Dead Outs, Now What?

QUESTION

Hello,

Can you give me some advice or suggestions on what to do with my old frames from three dead outs that I have this year? I have many frames that are just old comb, and many that have fully capped honey in them.

Could I just put the capped honey frames in a box and open feed the other hives I have? My hives died out because of low numbers, and mites.

Thank you for your help.

Mark

ANSWER

Good morning Mark.

Here are bunch of things to think about and that you should keep in mind.

In the wild, when we had lots of honey bee colonies living in hollow trees, before Varroa, they would only live in there three to five years before the colony swarmed many times, absconded or died out. When they died out, that left a significant amount of old, dark, used comb behind. Honey bee foragers are environmental samplers. As they bring nectar and pollen/bread in, they bring along lots of other stuff. So, they’re old comb is a reservoir of viruses, bacteria, bacterial spores, environmental chemicals and agriculture and home owner chemicals.

Beeswax, as a fatty acid, absorbs and hangs on to lots of things. The comb is dark because as honey bees develop into adults in the cells, they shed ‘larval skins’ that are in layers and layers and layers and viola, dark comb. When the colony was no longer active in that site, mother nature had a solution to remove old comb and the disease reservoir. That solution is wax moths. Wax moths want to reproduce, survive and move in as this old comb and larval skins are a food resource for their growing larvae. The wax moth larvae eat and destroy the comb, as you may have seen before, and thus significantly lowers the ability of disease and chemicals to be a future factor in honey bee health for the next colony that moves into this space. Wax moth in this context is the honey bees’ and the beekeepers’ friend. But we as beekeepers have been told to keep wax moths from destroying our stored comb especially.

There is information available that shows that removing three frames or so of old comb every year and replacing with new foundation can lower disease issues in honey bee colonies. We are in fact acting as surrogate wax moths.

Per your question, get the old comb out, render it for whatever beeswax might still be there or just throw them out and start ‘fresh’. Then begin with the every year, three combs replaced management tool.

If your colonies died from high Varroa levels, remember the colony did not die from Varroa mites, it died from the viruses that Varroa bring to the party which then lowered immunity in individual honey bees and the colony in general. Those viruses will be in the honey as well. Whether they will be infective if fed back to other colonies is a toss-up. Being a beekeeper in 2023 is like going to Las Vegas.

All that boils down to you have to make you own decision now. All the best. Hang in there.

Which Bees are Better?

QUESTION

Two native bees Habropoda laboriosa and Voccinium agustifolium are only two of the many pollinators for the low bush blueberry that are similar to the bumblebee. Why are honey bees promoted as blueberry pollinators rather than providing the much more efficient native bees? Is it just the financial aspect or am I missing something?

Tim Fulton

ANSWER / Earl Hoffman

I turned this one over to Earl Hoffman.

Hello Timothy Fulton.

Thank you for the excellent question on native bees vs Apis mellifera.

The economics of pollination require a high density of pollinators per acre because of the density of crops that need the transfer of pollen to create fruit.

Most native bees are not social bees, but solitary bees. They have nests that do not have thousands of foragers but only have, at most, hundreds of foragers.

The other aspect of Apis mellifera is easy propagation of the species. Queens and drones of honey bees are created with little effort by beekeepers. This allows thousands of hives to be created each Spring during pollen and nectar cycles.

Bumble bees and other native bees are thousands of times more difficult to propagate. There are only a few companies in the world that produce native bees for sale. These nest boxes are sold to greenhouses and other niche markets. They are very expensive and are only viable for a short period of time.

So I repeat my reply to your question on why native bees are not used to pollinate fruits like blueberries. Honey bees are more abundant and much cheaper to propagate. There are about two million beehives in the U.S. The native bee breeders produce thousands of small nest boxes each year and those are used in greenhouses worldwide. They are very expensive. Approximately 10-20 times more expensive. And again, I repeat these native bee boxes only have a small nest that lasts weeks, not years.

Last, some native bees are not propagated because either man has not learned how to control the creation of queens and drones or the cost and economics of such activities are not cost effective. It costs more in labor and time to create them than what the pollination revenue is worth. You cannot spend a million dollars to make a thousand dollars in pollination fees.

Please ask more questions as you see fit.

Thank you!

Earl Hoffman

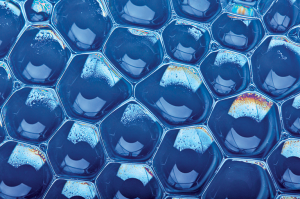

Hexagonal Cells

QUESTION

Hi Jerry, thanks for all the great info in BC… I have a quick question regarding the bees making their own wax foundation. In reading on the web and elsewhere, there seems to be two conflicting theories about how this is done. One says the bees themselves construct the new foundation cells one by one in a hexagon pattern right from the beginning. The other says they create roughly cylindrical cells first which, when pushed together as the foundation expands, are forced from the cylindrical form into that beautiful and space-maximizing hexagonal shape. Which explanation is correct?

Dan Smith

ANSWER

Hey Dan,

Check out https://nautil.us/why-nature-prefers-hexagons-235863/. Good article.

And yes, both are correct. We humans have made foundation with the starter hexagonal shape to save the bees time and beeswax resources. If you have seen free form comb not made using the hexagonal foundation starter, the cells are more roundish than hexagonal. You can see the kind of intermediate shapes.

In the image above, when soap bubbles, in this case, are formed together, they form hexagons as this shape is more stable and the bubbles can use this structure together to last longer.