By: David MacFawn

Note: all data, numbers, tables and equations used in this article was collected in late-2019/early-2020.

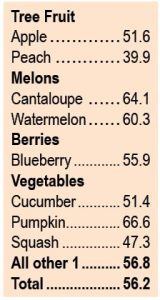

Crop pollination can be a viable line of business in addition to honey production for the small to medium size (less than 75 colonies) beekeeper. Pollination rates vary across the United States and by crop.1 The beekeeper has to decide what their time and effort is worth and if they have the means to move the hives. The small-scale beekeeper can often do an excellent job pollinating vegetable crops since vegetable crops are usually fields less than 10 to 20 acres.

A price, volume, distance relationship exists in the pollination business. The more hives you transport, the further distance the beekeeper can move them for a given price. Eight to ten colonies can be hauled in a pickup truck single stacked. The number depends on if you have a short bed or long bed pickup. A utility trailer can also be used to keep from making multiple trips. The trailer can be left in the field locked to reduce lifting the hives.

The average pollination rate is typically one to two colonies per acre for most crops.2 The grower will typically tell the beekeeper how many colonies they want. An agreement needs to be made as to when the beekeeper will move their hives into the field, and where the hives will be placed.

Sometimes the beekeeper may realize a super of honey if a nectar flow is transpiring during pollination. This super may be from the target crop or it may be from other sources. Hence, the beekeeper needs to take this into account when pricing as it still costs money to move colonies into a field for pollination. Since bees forage close to the hive upon moving, they will pollinate the crop and may also gather nectar from surrounding areas. Regardless of the honey quality, a super of honey may be used for sustaining the colonies if not extracted.

The beekeeper may want to consider eight frame equipment for pollination. Eight frame equipment is lighter than ten frame equipment and it is easier to get your hands around to lift. It also stacks better in a pickup truck or utility trailer; smaller footprint.

Some factors impacting pollination profitability include:

Mileage Cost

The distance traveled is a cost of business and impacts profitability. The smaller the number of hives transported at one time, at a given vehicle mileage rate and labor rate results in reduced profit margins.

Labor Rate

Labor costs impact profitability. Labor is required to care for the bees, transport of the hives and to load and unload the hives.

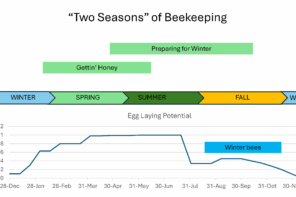

Number of Crops Pollinated and Nectar Flows

The number of times different crops are pollinated in a given year impacts how many times your equipment costs and colony maintenance / care are distributed. Often in the southeast, you can make a honey crop prior to pollination. Three or more nectar flows and/or crops pollinated is recommended.

Equipment Cost

Cost of equipment impacts profitability greatly. Cost of new equipment, whether expensed at one time or depreciated over a number of years, increases one’s expenses. The beekeeper may want to consider good, used equipment to reduce initial equipment investment.

In the southeast, after initial assembly and painting (primer and at least two coats of high-quality paint), woodenware’s average lifespan is eight to 10 years prior to refurbishment. It pays to maintain your existing equipment as much as possible. As long as the equipment is structurally sound, it is usable. Good quality duct tape can be used to seal holes during transport. One way you can reduce expense is make your equipment last as long as possible, i.e. longer than an average five-year depreciation period. New equipment costs money, even if it is initially totally expensed or depreciated. New equipment expenses can make the difference between making a profit or loss.

Depreciation Period

The depreciation period duration impacts the amount of equipment that is written-off every year. The shorter the depreciation period, the larger dollar impact during the years the equipment is being written-off.

Cost of Bees

How much colony replacement bees cost every year also impacts profitability. Three-pound packages with a queen costs anywhere from $80-$100 package producer direct, and the cost of a nucleus colony (NUC) was approximately $150-$165 in 2018. Splitting colonies and installing a mated queen or queen cells is a less costly method to increase your colony numbers.

Life of Bees / Mortality of Bees

How long your colonies survive impacts your colony replacement costs. You want your colony to live as long as possible to reduce your colony replacement costs every year. Colony mortality is reported being around 40% (Bee Informed Partnership 2017-2018 Winter).

Time Required to Work Bees

How much time per colony to work bees every year is a large impact on costs. You want to take the necessary time to maintain your colonies but at a minimal cost.

Cost of Sugar/Feed

Often during pollination, you may need to feed the colonies if they lose weight, such as on low producing crops like cucumbers. Beekeepers have the options of feeding white sugar or high fructose corn syrup (HFCS).

Travel Speed Resulting in Travel Labor

Travel speeds impacts your labor cost. While the beekeeper wants to minimize their labor, you want to do so safely.

Treatment Cost

Costs are associated to medicate your bees for Varroa in addition to other issues. This is a necessary expense to keep your bees healthy and is cheaper than letting your colonies decline. Along with the cost of medication comes the cost associated with travel to administer the medication.

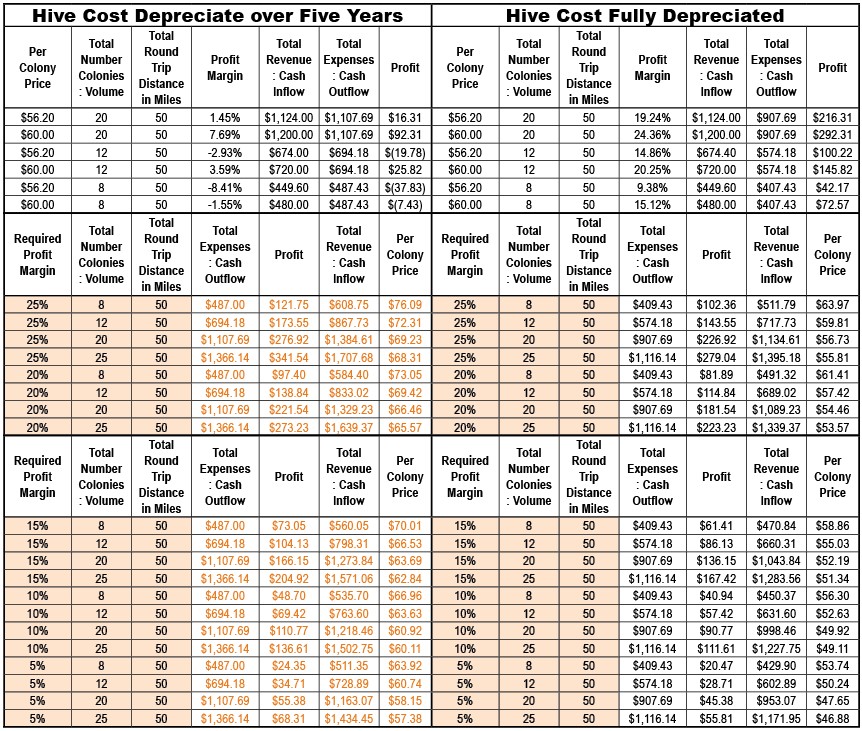

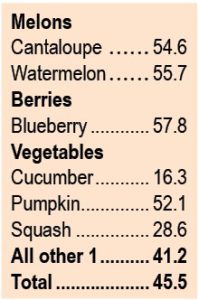

Table 1 lists several possible per colony prices, total number of colonies and round trip distances as an example. The table is divided into depreciating equipment over five years on the left, and equipment fully depreciated on the right. Table 1 is for three nectar flows and/or pollinations. The beekeeper can spread their costs over more nectar flows and/or pollinations reducing their cost per nectar flow and/or pollinations. Note, Table 1 accounts for most major costs, but it really only has ball-park numbers since every person’s circumstance is different. There is a niche market for the small pollinator with smaller size fields. Also note the distance traveled impacts profitability as does the per colony price and total number of colonies transported.

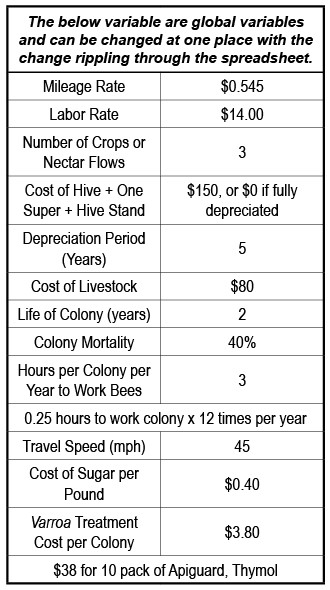

Table 2 lists the assumption this analysis is based on. This is a small-scale pollination pricing analysis. Assumptions include:

- Beekeeper has vehicle and homeowner’s insurance. Verification of coverages needs to be determined.

- Beekeeper already has bee suits and other miscellaneous equipment.

- Assumes no hired help. The beekeeper is doing the pollination themselves.

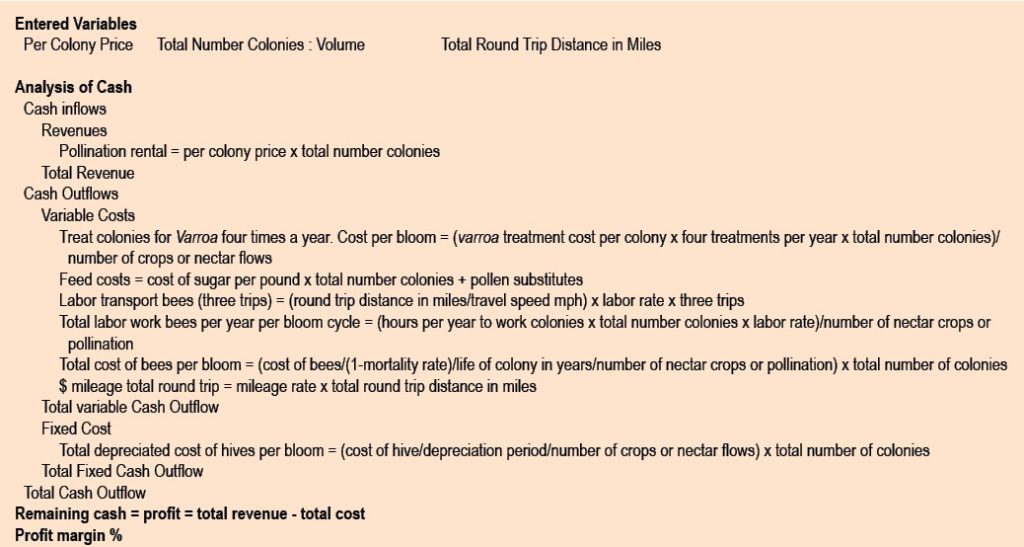

Table 3 contains the equations this analysis is based on to generate Table 1.

Small-scale pollination (less than 75 total colonies) can be a viable added business in the southeast in addition to honey production. It is a niche market that large-scale pollinators have difficulty servicing profitability. While all the variables are important, equipment costs can determine if the beekeeper makes a profit or not. Utilizing used equipment should be considered to reduce equipment costs. Also, three or more nectar flows and/or pollination events are necessary to make money to spread your costs over. The beekeeper has to determine what their time is worth and how much they can charge per colony rental. The small-scale beekeeper can often pollinate vegetable crops well since vegetable crops are usually smaller size fields. In the southeast, a beekeeper can often make a honey crop in the Spring and do two or more pollinations in late Spring, Summer and Autumn. It takes time to develop pollination contacts and a pollination business.

Everyone’s financial situation is different. If you are interested in receiving the spreadsheets used to create the data in this article with up-to-date financial details like federal mileage rate, etc., contact David MacFawn at dmacfawn@aol.com.