A Fall tradition not to be taken for granted

by Dewey Caron

Fall is time to market pumpkins and honey. September is National Honey Month, October includes Halloween and November brings Thanksgiving. Without bees, as beekeepers but too few pumpkin-lovers know, there would not be pumpkins nor other traditional foods we give thanks for at Thanksgiving.

The good word is there are adequate pumpkins this year in contrast to last year when the news was not so good. Too much rain brought flooding which washed out pumpkin fields from the Mid-Atlantic to New England (especially New York and Vermont) and too much rain in the Carolinas resulted in a short crop with too few pumpkins to export pumpkins to areas with short supplies from states further south.

Pumpkins, like honey, are often a value-added market product of smaller family farms. Edible Portland Magazine (2013 Fall edition) had a nice article about brothers Dylan and Darren Wells and their “Autumn Harvest” market brand. They specialize in miniature pumpkins and gourds which Dylan, now 22, grows on a 200 acre farm. In the Fall, newspaper and magazine articles abound featuring local farms offering pumpkins for sale directly to the public through U-pick or farm stands. Some growers invite the public to “Come out to the farm” to select your own. Visiting a field full of pumpkins makes for an attractive afternoon family outing.

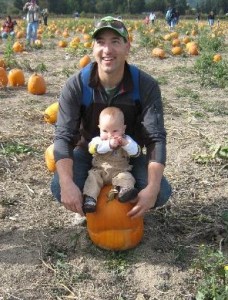

I enjoy taking the grandchildren to a local pumpkin farm in the Portland area. If you have never had the pleasure, I encourage you to go and enjoy a nice weekday or weekend afternoon at a pumpkin farm in your area. Look for websites or flyers that list local farms and what they sell. Many sell honey, sometimes the honey production of the beekeeper providing pollination service, along with the pumpkins and other typical farm produce. Don’t pass up the fresh apple cider.

Pumpkin (called a fruit) is a native of the Americas. It is related to zucchini and spaghetti squash (squash are in contrast termed vegetables). Our standard Halloween jack-o-lanterns and edible pumpkin pie varieties have been shaped by humans for some 800 years. They vary widely in size from miniature to giants, over 1500 pounds, for special local fair competitions.

Most of the cucurbitaceae family (including pumpkin and squash) are tropical or subtropical but there are a few wild species in North America – most natives have high levels of cucurbitacins which give the skin and innards their bitter taste. They typically grow by vining as many home gardeners learn when one or two squash/pumpkin plants ‘take over’ the garden. In addition to pumpkin and squash, gourds, melons and cucumbers, watermelon, luffa (sponges) and chayote are other familiar cucurbits. Like our samples of local honey, taste and color vary extensively in pumpkins and squash.

Squash bee

The American natives, pumpkin and squash, rely on native squash bees (about three dozen indigenous species) for pollination. Squash bees (two different genera Peponapis and Xenoglossa) are very hairy and only slightly smaller than the honey bee. They are ground nesters. Populations vary wildly from one site and season to another. Females make a foot-long or deeper, pencil-thin tunnel in the soil with side partitions. Though male and females forage the flowers, only the females collect pollen which they mix with the nectar to form a food mass for their egg, deposited on the food. Male and females rarely visit other flowers, even relatives such as melon or cucumber.

Male squash bees spend the night in unopened flowers. Although they do not collect the pollen, they have been found to still be efficient pollinators since they become covered with the pollen grains overnight and then transport it to other flowers as they search for females in the morning.

Squash bees are the opposite of generalist honey bees – they are specialists. Jim Cane of the USDA Pollinating Insects Biology Management Lab in Logan Utah has been surveying abundance of the native squash bees and their pollination biology. Found throughout the U.S., squash bees are less common in the east and very uncommon in the Pacific Northwest. Bumble bees are also good pollinators of cucurbits.

Cucurbit flowers are only open in the morning hours so populations of pollinators need to be high to realize desired commercial crop yields. Squash and pumpkin flowers can be pollinated by larger-bodied bees but modern farming practices and fall marketing demands means pollinator availability may not meet the demand. So to insure adequate pumpkins, growers rent honey bee colonies as ‘insurance’ in case too few native bees are present to pollinate the flowers. Homeowners too sometimes find they can grow lots of vines but none or too few fruit – zucchini squash seems to be the exception.

Many pumpkin pollinators are smaller-scale beekeepers. Selling pumpkin pollination however is not straight-forward. The native pumpkin and squash are rather poorly pollinated by honey bees. In my survey of pollinators on both east and west coasts, the rental fee ranges from as low as $30 to over $75 per colony at a density of one colony for every two acres.

A study in New York looked at identifying landscape-level impacts on bee-mediated pollination services using pumpkin pollination as their study focus. An OSU (Ohio State) graduate student Jessica D. Petersen looked at landscape diversity by calculating percentage of semi-natural grassland in the landscape around pumpkin fields. She counted the number of bumble bee (Bombus impatiens) and honey bee visits. Both positively affected yield. The study concluded that pumpkins grown in areas of highly diverse cropland/forest sites or areas of high grassland landscapes benefit more from bumble bee visitation. Landscape diversity did not increase honey bee visitation to flowers.

Since bumble bees benefited from a diverse landscape and their visits to flowers positively impacted pumpkin production, the authors recommended conservation of a diverse landscape to support improved pumpkin production.

Other studies have demonstrated that increased pollinator diversity (competition from more than a single flower-visiting bee species) improves yield in other cucurbits (watermelon and cantaloupes), sunflowers and blueberries.

Growers can use this information to decide where to plant pumpkins to improve the potential for high yields and to identify scenarios where landscape diversity could be increased, plus better determine where supplementation with honey bee colonies might be needed.

All cucurbits require multiple flower visitation with pollen transferred to all parts of the large stigma to yield perfect, well ripened and properly shaped results with the characteristics highly important for marketability of these commodities. Supplemental rental of honey bee colonies as ‘crop insurance’ still is the best alternative.