By: Mariann Fercsik

It’s Not The Bees

“With the introduction of China’s Home Responsibility System in the 1980s, the farmers of Hanyuan County in Sichuan Province found it economically beneficial to replace their rice paddies with fruit orchards.

The mountainous slopes of the region lent themselves well to fruit production, particularly pears, for which Hanyuan County is now renowned.

Any crops grown beyond the quotas of China’s collectivized farming program could now be sold on the open market and, in order to maximize their yield, the farmers began to increase their use of pesticides.

This, in turn, had a negative effect on the population of the natural pollinators, and the local beekeepers were driven to relocate their colonies out of the cultivation areas.

With the disappearance of the bees, along with the desire to control the quality and purity of the pear varieties, the farmers began the labor-intensive task of pollinating their crops by hand.

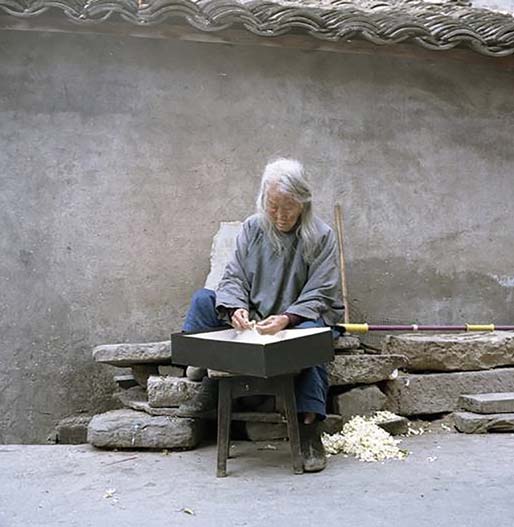

Every member of the family is involved in the hand-pollination process in some way. Old woman selecting the stamens from the Yali (main pollinizer) flowers. This is a preparation process before the farmers go to hand pollinate. Farmers need to dry the stamens on 20-23°C temperature.

An aged farmer works on his orchard. In Juixiang even the oldest are capable to complete physically challenging tasks such as pollinating each blossom one by one, even in the most diffi cult and dangerous environment.

Chen Tao pollinating the family orchard in Dalian. He uses a duster made out of chicken feathers. The duster touches pollen mixture, and then shaken over the target pear trees for one to three times a day in order to ensure adequate pollination of the pears.”

A farmer prepares a small pollination stick. The feathers are degreased in alcohol before tying on the bamboo stick.

Flowering pear trees in Hangduan mountains. The average number of pear trees owned by each household is around 80-110. To pollinate these trees three to six polliniser trees are suffi cient. A 10 year old polliniser tree can produce fl owers enough to pollinate approximately 50 trees.

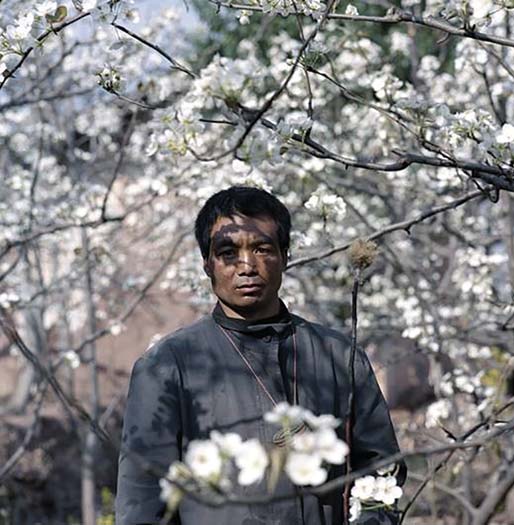

Shiqin Tan stands amongst his pear orchard. He planted the trees 20 years ago. His orchard consists of 45 trees. A person can pollinate 30-40 trees a day.

The transport of masses: motorcycles are the most common form of transport in the mountainous area of Jiuxiang.Young couple on its way to start pollinating their pear trees.

In preparation for hand pollinating. Woman brushing off the stamens from the Yali variety. She collects them into a pot before they start the drying process.

With simple tools such as a bamboo stick and chicken feathers they embarked on a journey of learning, not just how and when to pollinate, but when to collect the stamens, how to dry them, and which varieties respond to which pollinizer.

Additionally, not all the pear varieties are self-compatible, so cross-pollination is needed in order to achieve a desirable crop.

With skill and patience, the farmers can produce high quality, high yield product, albeit with increased labor costs than if they relied on nature alone.

As industrialization continues to push up the cost of hiring a workforce, the farmers must find an alternative way of cultivating their crops in order for them to remain viable. With pear production accounting for 40 to 50 percent of the household income, the stakes are high and adaptability will be key to their success.

The return of the natural pollinators is possible, but this is unlikely without a coordinated approach to limiting the use of agrochemicals.

What the future holds is uncertain and further work is needed to find a successful solution that balances the economy with ecology.”