Click Here if you listened. We’d love to know what you think. There is even a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

Becky Masterman earned a PhD in entomology studying hygienic behavior at the University of Minnesota and is currently a host for the Beekeeping Today Podcast. Bridget Mendel joined the Bee Squad in 2013 and led the program from 2020 to 2023. Photos of Becky (left) and Bridget (right) looking for their respective hives. If you would like to contact the authors with your inspirational apiary inspector stories, please send an email to mindingyourbeesandcues@gmail.com

Minding Your Bees and Cues

Confessions of Upper Winter Entrance Beekeepers

By: Becky Masterman & Bridget Mendel

We never thought our wintering methods were scandalous, let alone distressing, but here we are. Our low R factor cardboard boxes, moisture boards, and use of an upper Winter hive entrance have proved successful for decades in our cold Minnesota climate, but are shockingly out of style, as if we were promoting the use of a heated brick to warm our cars in Winter! This is due to a great deal of excitement about the nuances of insulating hives. We have nothing against the insulating trend which can help with evening out cold Winter temperatures. But note we use nuance not life or death catastrophe to describe the topic; concerns about evening temp fluctuations are the icing on the mite-infused cake of overwintering worries.

What we are concerned about is that, for early-stage beekeepers, the hype about insulation opportunities obscures its relative insignificance compared with other overwintering concerns. How to insulate your hive is equivalent to researching Winter coats. While some insist on down, and others maintain that the important thing is coat length, comfort is irrelevant if you don’t have good healthcare, first. And folks have lived in Minnesota for thousands of years before the dawn of Arc’teryx.

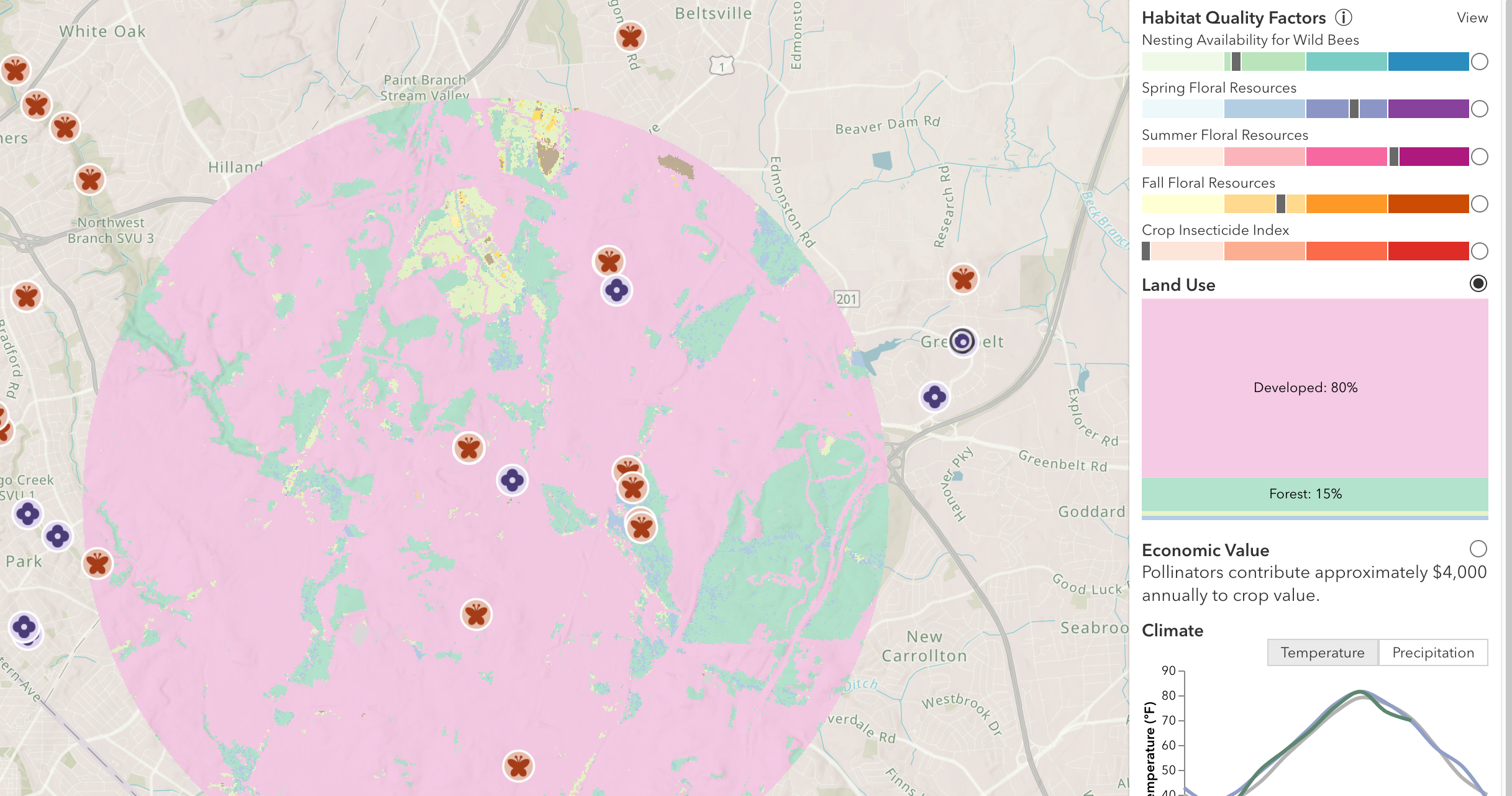

We all agree that beekeeping management advice is local. How you manage your bees is a complex formula using information on available habitat like when to expect major and minor nectar flows. Knowing the local environment will inform colony growth as well provide insight about brood breaks due to resource dearth (a welcomed reminder from a wise beekeeper from Tennessee). Understanding your local environment will help you understand when you need to supplement colony nutrition. Understanding your local climate will inform how your colonies will need to be prepared for winter and what Winter feeding options (if necessary) are available.

We also think that local isn’t enough when it comes to management advice. We also let the bees (and their hive configurations) inform us of how we will prepare them for Winter. If they shut down brood rearing quickly when pollen and nectar are scarce in the Fall, we assume they will be more conservative with their Winter honey stores. If brood is more abundant, we see more future mouths to feed and a potentially larger Winter cluster. We help them prepare with 2:1 heavy syrup. Single deep colonies can store enough honey to survive a Minnesota Winter if we provide time for them to accept and process heavy syrup.

Back to our upper Winter hive entrance. First, we will share some quick Twin Cities, MN Winter lowlights: 1) we average 19 days of below 0 degrees F temperatures; we average 55 days of 32 degrees F as the daily high temperature; and 3) the current average winter low temperature is minus 15 degrees F. These temperature data make beekeepers very nervous when we casually mention that not only is there a bottom entrance in our hive setups, but also a top one. Beekeepers who are nervous about an upper entrance might benefit from Dr. E.J. Anderson’s wintering experiment report which describes both the benefits of winter insulation (fewer temperature extremes), but also shares data about the limited heat loss that was recorded through the upper hive entrance. Importantly, this opening is likely a helpful way to mitigate excess moisture and support winter flight if the bottom entrance is blocked with dead bees (Anderson, 1943).

We understand that a tree nest cavity is very different than a Langstroth box. Our gentle response is that our Winter clusters are larger than those in a tree cavity. Our animals (the cluster) are bigger and generate more heat than smaller clusters. Our Winter management choices are based on our boxes and our bees and their needs. We also confess that we are sometimes worried about our bees being too warm and consuming their Winter stores quickly if the clusters are large and temperatures are warmer than usual.

We learned top entrance wintering from our time spent studying and working in the University of Minnesota (UMN) Bee Lab. Based on wintering research, this method was adopted by Dr. Marla Spivak from Dr. Basil Furgala after his 1992 University of Minnesota Bee Lab retirement. Recently, Dr. Katie Lee, UMN Apiculture Extension educator, has assumed leadership of the Beekeeping in Northern Climates (BINC) beekeeper instruction program and revised the course. In its 3rd edition, the BINC manual (we both served as editors) is available as a free pdf online https://beelab.umn.edu/manuals.

While it isn’t often that management decisions divide beekeepers (pause for a deserved laugh or at least a smile), the debating of wintering methods is not a new room divider. In the 1942 edition of Gleanings in Bee Culture’s A Symposium on Wintering, E.R. Root wisely stated that winter methods across the country should vary based on climate and moisture. While we greatly enjoyed the upper entrance discourse in this symposium and reading about wintering honey bee colonies in the colder-than-Twin-Cities city of Warroad, MN, we will use our final words to move on to what we worry about most for our Winter bees.

In our colonies and in yours, we fear the impact of Spring, Summer, and Fall varroa infestation on wintering success. We are concerned about the messaging that if you can’t winter bees successfully, you need a different wintering insulation method. At the risk of overgeneralizing, we want beekeepers to assume that if they are struggling with winter losses, their first question needs to be whether they aggressively managed Varroa destructor season long and kept their bees as free from varroa associated viruses as possible. We aren’t worried about cold temperatures killing colonies. We aren’t worried about colonies with proper Winter stores starving in cold Winters. We aren’t worried about the upper entrance in our hives (see our January pictures). We are worried about colonies with varroa infestation raising weak, sick bees in the late summer that die in the Fall and Winter.

As far as the hive bodies that provide insulation, we look forward to research that reports more ways they can help reduce temperature stress on different sized colonies. We are also excited about science that will someday report on the nuances of how insulation can support clusters based on temperature and humidity conditions in different climatic regions.

We’ll end by recommending a few beekeeper resources for help with Winter management decisions:

Why Did my Honey Bees Die? video by Dr. Meghan Milbrath, Michigan State University Assistant Professor of Entomology https://pollinators.msu.edu/programs/keep-bees-alive.aspx

Honey Bee Health Coalition’s Varroa Management Resources https://honeybeehealthcoalition.org/resources/varroa-management/

Honey Bee Health Coalition’s Nutrition Guide (includes information on Winter supplemental nutrition)

https://honeybeehealthcoalition.org/nutritionguide/

References

Heated Brick – https://www.post-journal.com/news/local-news/2022/12/portable-foot-warmers-used-in-horse-drawn-carriages-churches/

What Winter MSP https://www.weather.gov/media/mpx/Climate/What%20Winter%20MSP.pdf

Honey Bee Forage Map https://honeybeenet.gsfc.nasa.gov/Honeybees/Forage.htm

A symposium on wintering. Gleanings in Bee Culture 1942-09: Vol 70 Iss 9 pp. 554-556 https://archive.org/details/sim_gleanings-in-bee-culture_1942-09_70_9/mode/2up

Anderson, E.J. Gleanings in Bee Culture 1943-12: Vol 71 Iss 12 pp. 681-683, 715. https://archive.org/details/sim_gleanings-in-bee-culture_1943-12_71_12/mode/2up

A favorite historical summary about the beekeeping wintering debate

B. Furgala XVI Fall Management and The Wintering of Productive Colonies. 1975 edition of The Hive and the Honey Bee. Dadant and Sons, Inc. pp. 471-490.