By: David MacFawn

Here’s how and when in the SE U.S.

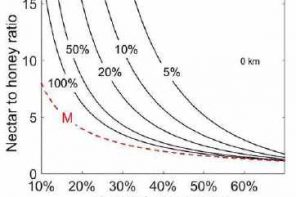

Splitting a colony is one way to control swarming. It is also a way to make increases to make up for lost colonies. When making a split, the new split should contain capped worker brood with some worker eggs and larvae, honey, and pollen. It takes workers consuming honey and pollen to produce worker jelly to feed worker larvae, to ensure worker brood are completely fed. During the Spring nectar flow in any places there is a tradeoff between making splits and obtaining a honey crop.

Enough nurse bees are required to care and cover the brood on cool nights. Older field bees are required to for water, pollen and nectar to feed the young larvae. When making a split, if swarm cells are available, the beekeeper will the time needed for a split to become a functional colony. With a capped swarm or queen cell, it takes an average of about seven days for the queen to emerge from a freshly capped pupa. Add another ten to fourteen days for the queen to mate and start laying plus another 19-21 days on average for first workers to emerge for a new split. This means it takes approximately 36 to 42 days for new workers to emerge. Add an additional 18 to 21 days for workers to start foraging means it will take approximately seven to nine weeks for these new foragers to start collecting nectar, pollen, or water.

Most colonies swarm either right before or during the nectar flow. However, if mated, local queens are used the wait time for new foragers can be reduced by approximately 14-17 days compared to moving a queen cell (seven days for emergence and seven to10 days for mating). If a walk away split is made, where the bees raise their own queen, it will take approximately 15 to 17 days for the queen to emerge, 10 to 14 days to mate and start laying, 19-21 days for workers to emerge in a new split, and an additional 18 to 21 days to become field bees. In total that is approximately nine to 10 weeks to produce field bees from a walk away split. This maturation time will impact honey production. Hence, the old saying you can make either bees or honey is true.

When making a split, the split should be closely monitored for about three weeks to see if you need to add another frame of brood. Bees typically only live an average five to six weeks during warm weather and it may take 6 to 10 weeks to obtain field bees. Splits should be fed sugar syrup as a safeguard with the understanding that during the nectar flow stored syrup may intermingle with collected nectar. Bees typically will stop using sugar syrup when fresh nectar is available. However due to the reduced size of a split, and normal population losses, it is wise to offer sugar syrup until they become a functional colony. If another frame of bees and brood is added from a strong non-split colony, and if the nectar flow is ¼ to ½ complete, the brood that is removed from the strong non-split colony will minimally affect honey production. This is because of the time needed for any brood taken from the donor hive, has yet to complete its development into mature field bees.

| Type of split | queen

Develop |

emerge/

mate/lay |

workers

emerge |

total to worker

emergence |

field

bees |

total to

field bees |

| Mated queen | 0 | 3-7 | 19- 21 | 22-28 days

3.1-4.0 wks. |

18-21 | 40-49 days

5.7- 7.0 wks. |

| Capped Queen cell | 0-7 | 10-14 | 19-21 | 29-42days 4.1-6 wks. | 18-21 | 47-63 days

6.7-9 wks. |

| Walk-away/egg | 15-17 | 10-14 | 19-21 | 44-52 days

6.3-7.4 wks. |

18-21 | 62-73 days

8.9-10.4 wks. |

When selecting a frame of brood, you want mostly capped brood with some eggs and larvae. Capped brood has completed its feeding stage which means the split does not need as many nurse bees. The eggs and larvae are an insurance policy in case the bees need to raise a new queen. Also, you want all different stages of brood so you have a continuous supply of bees. A minimum three frame split is recommended with a frame of capped brood, eggs and larvae, honey, and pollen. A five-frame split is better with all stages of brood since it will build up quicker than a three-frame split.

Figure 3. Frame of worker brood with eggs and larvae on the top. (MacFawn photo)

Figure 3 is a good frame for a split. It contains a lot of capped worker brood, with some larvae and eggs on the upper part of the frame. Typically, at least one total deep frame with brood should be used in addition to a frame of honey and a frame of pollen. The brood frame should be placed in the middle of the three frames for warmth. All three frames should be covered with as many bees as possible.

The split should typically be moved greater than three miles to retain your field bees. If you decide not to move the split and leave it in the same beeyard, the field bees will return to the original location. Leaving the split in same beeyard will still work if you have enough nurse bees to cover the brood. The split needs to be monitored closely and another frame of bees and brood added if necessary. The split should be fed sugar syrup.

Figure 4 has a lot of eggs and larvae for a split without a lot of nurse bees. The eggs and larvae require a lot of nurse bee visits with the resulting large amount of nectar, honey and pollen to feed these larvae.

Figure 4. Eggs and larvae with some capped worker brood. (MacFawn photo)

Figure 5. Frames of pollen from various sources – different color. (MacFawn photo)

This frame may not be the optimum choice for a split. An optimal frame contains capped brood in addition to larva and eggs. This will allow a continuous supply of bees until a queen starts laying.

Figure 5 is an excellent frame of pollen for a split. Note the various pollen colors indicating the pollen is from various sources. This results in a varied pollen diet. It takes brood, honey, pollen, and bees for a split to be successful.

Three or more frames for the split should be placed in the middle of a brood chamber with additional frames on either side. During a nectar flow, the additional frames may contain foundation since the bees will typically draw the cells out. If a split is made after the main nectar flow, frames with drawn comb are preferred. The colony should typically be treated for Varroa prior to the split to ensure the treatment chemicals do not interfere with requeening.

In any locations, splits may be done during the Spring nectar flow, in June after the nectar flow is over while the colony still has a lot of bees and brood, and in the August time frame. Splitting in August with young local mated queens is good preparation for the next year when queens are not available during the typical Spring buildup period.

Figure 6 would make a good brood frame for a split. However, one should note it does not have an insurance policy of additional eggs and larvae. Enough nurse bees and field bees need to be retained to cover the brood on cool days and nights.

Figure 7 shows fresh white wax and is typically one of three signs a nectar flow of occurring. The other two signs are fresh nectar in the combs, and the bees flying with “a sense of purpose,” and not languishing as they leave the hive.

Figure 8. Swarm cells on the bottom of a frame. (Carpineto photo)

Figure 10: This frame was part of a split where the queen did not take for some reason; hence, the bees built emergency cells. This split should be monitored closely to ensure they have enough bees to get them through until the foragers start maturing. Note the lack of brood on the frame. This split may not have had a laying queen. This split should also be monitored to determine if another frame of brood and bees should be added to sustain the split.

When assessing queen cells, you want larger, more sculptured cells. The more sculpturing the better the cell is considered. Usually Supercedure / emergency cells are toward the upper part of a frame and not as numerous as swarm cells toward the frame’s bottom.

Figure 10. Swarm cells/cups ont he frame bottom with two emergency cells midway up the frame. Note the pollen between the queen cells and the honey in the upper left of the frame. (Carpineto photo)

Splitting a strong colony is one way for swarm control and to make increases. A five-frame split is preferred, with the equivalent of a frame of brood/eggs/larvae, a frame of honey, and a frame of pollen. The split should be monitored at approximately three weeks to determine if additional brood and bees need to be added. In South Carolina, splits may be created at least three different times of the year. In the March through May time-period when the spring nectar flow occurs, in June after the spring nectar flow, and in the August time frame. Usually there is a tradeoff between making splits and making a honey crop.

References

1. Personal discussions with Randy Oliver

2. Making splits, David Tarpy, MP4 video, North Carolina State

Extension

3. “Increase Essentials, second edition”, Lawrence John Connor

, Wicwas Press, ISBN 978-1-878075-35-2