Part 1

By: Darryl Gabritsch

Inspecting a hive is only one part of colony management. If you see an issue while inspecting a hive there are various management techniques to do depending on what you see. This article will be three parts. Part 1 covers the concepts behind a hive inspection. Part 2 covers pre-inspection procedures. Part 3 covers the actual hive inspection procedures.

How often and when you inspect a hive totally depends on your lifestyle, beekeeping experience, what your philosophy is and what the purpose of the inspection is. All inspections should be systematic and have a specific purpose. Why are you opening a hive? Are you simply lifting the hive body to check under the frames for swarm cells (cold months)? Are you opening the hive to remove frames to do a detailed inspection (warm months)? Are you opening the top to simply look at the cluster location and strength, or simply checking a hive top feeder?

How often and when you inspect a hive totally depends on your lifestyle, beekeeping experience, what your philosophy is and what the purpose of the inspection is. All inspections should be systematic and have a specific purpose. Why are you opening a hive? Are you simply lifting the hive body to check under the frames for swarm cells (cold months)? Are you opening the hive to remove frames to do a detailed inspection (warm months)? Are you opening the top to simply look at the cluster location and strength, or simply checking a hive top feeder?

Most of us are just hobby beekeepers and have work and home life to balance along with beekeeping. Ask yourself: How much time can I dedicate to beekeeping? What skill level are you at? Are you a beginner beekeeper, a Master Craftsman beekeeper, hobby beekeeper, sideliner beekeeper, or commercial beekeeper? How much time do you have to manage the colonies? Do you mind if the honey bees swarm? Do you simply want to help the honey bees? What is the purpose of the inspection?

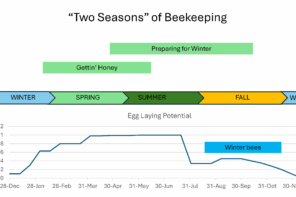

A cold weather hive inspection is very quick compared to a detailed warm weather inspection. In cold temperatures you might only open the top to look down at the frames to see the brood cluster and food stores, or you might tilt the hive body up to quickly check for visible swarm cells without removing frames. Remember the bees will form a cluster in the hive to protect the brood and queen when the temperatures get down to 57 degrees or lower. Don’t be confused if you see individual bees flying in lower temperatures. I have seen them do cleansing flights in temperatures as low as 45 degrees.

In warm weather you can do a detailed inspection by removing frames. As a general rule of thumb, I only open a hive and remove frames if the outside temperature is at least 64 degrees or higher, and if it is not raining to prevent killing brood and bees by hypothermia. I like to remove frames when it is on the cooler side of temperatures if possible and after the foragers leave the hive to forage.

How often you inspect a hive depends on your time available and philosophy. Remember the timeline from a new queen to emerge from an egg to emerging as a queen is 16 days. When you inspect a hive, you disrupt the bees for a few days while they figure out what you did; especially if you don’t put the brood back in the order it was found. To prevent putting the frames back in backwards I simply draw a line across the top on one end of all frames with a black Sharpie pen to help me keep all drawn lines on one end of the hive. Draw the line on the frames before you first put them in a hive since the bees will coat the frame with a thin layer of propolis. The marker won’t easily stay if you try to mark it after the propolis is on the frames.

How often you inspect a hive depends on your time available and philosophy. Remember the timeline from a new queen to emerge from an egg to emerging as a queen is 16 days. When you inspect a hive, you disrupt the bees for a few days while they figure out what you did; especially if you don’t put the brood back in the order it was found. To prevent putting the frames back in backwards I simply draw a line across the top on one end of all frames with a black Sharpie pen to help me keep all drawn lines on one end of the hive. Draw the line on the frames before you first put them in a hive since the bees will coat the frame with a thin layer of propolis. The marker won’t easily stay if you try to mark it after the propolis is on the frames.

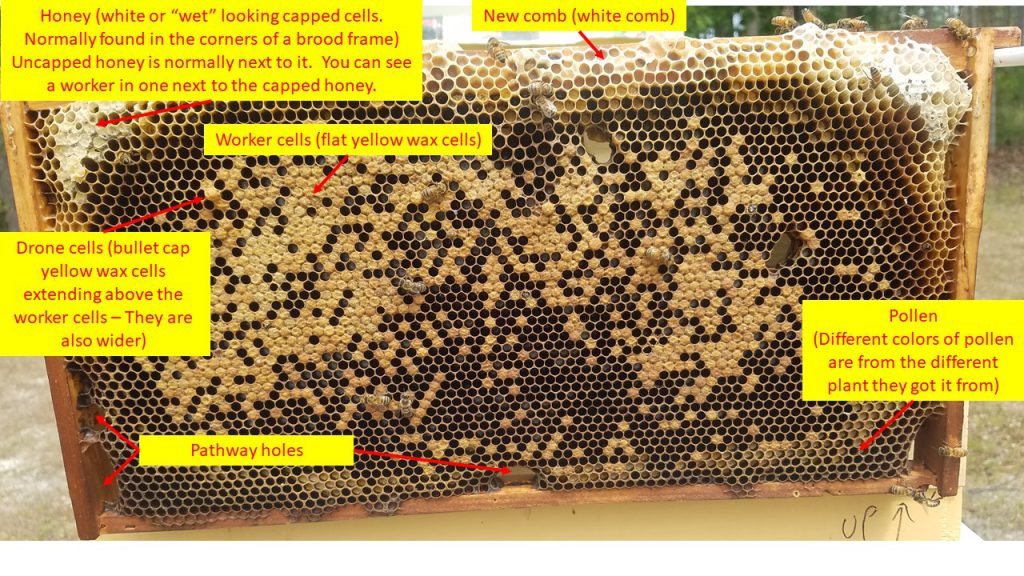

We encourage new beekeepers to inspect their colonies at least once every ten days to stay ahead of the swarm cycle and to learn what right looks like inside the hive. I recommend simply inspecting the colony once a week to keep a simple schedule. Ideally you have at least two hives, so you can compare one hive against the other if you see something weird in the hive. You can also take parts from a strong colony to give to a weak colony. Do you have a very weak colony? Give it a frame of brood, nurse bees, and food stores from a strong colony AFTER you first check the frame for the queen. All beekeepers should review reputable beekeeping sites to learn what the various diseases and pests look like, so that you will be able to recognize them when you see them.

New beekeepers may take 30 minutes or longer to inspect a hive while learning what right looks like inside a colony. A very experienced beekeeper can inspect a colony in about five minutes. Most beekeepers fall between the two extremes. Experienced beekeepers who don’t mind if their colonies swarm might only inspect every few months, or when they see indicators of issues such as pests, disease, very defensive colony, etc.

New beekeepers may take 30 minutes or longer to inspect a hive while learning what right looks like inside a colony. A very experienced beekeeper can inspect a colony in about five minutes. Most beekeepers fall between the two extremes. Experienced beekeepers who don’t mind if their colonies swarm might only inspect every few months, or when they see indicators of issues such as pests, disease, very defensive colony, etc.

There are many ways to inspect a hive. Remember the adage: Ask 10 beekeepers how to do something and you will get 12 answers; all will be right. This is how I do it: Do all preparations before opening a hive, inspect the hive, take appropriate management steps during or immediately after the inspection, and finally I mark the hive with notes and/or a signal such as a full red brick, half red brick, or stick depending on what I find.

There are many ways to inspect a hive. Remember the adage: Ask 10 beekeepers how to do something and you will get 12 answers; all will be right. This is how I do it: Do all preparations before opening a hive, inspect the hive, take appropriate management steps during or immediately after the inspection, and finally I mark the hive with notes and/or a signal such as a full red brick, half red brick, or stick depending on what I find.

Summary. Learning how to inspect a hive is a crucial step in your beekeeping journey. Having a systematic, purposeful inspection process will keep you focused on the steps needed to conduct a thorough, and eventually a quick, hive inspection. Knowing what to look for will help you determine what is normal and what requires further diagnosis and remedies. Beekeeping is both a science and an art. Beekeeping science is knowing the cause and effect of diseases and pests. Beekeeping art is balancing the various management techniques to keep healthy, strong colonies.

Darryl Gabritsch is a North Carolina Beekeepers Association Master Beekeeper and lives in NC with his family.