Click Here if you listened. We’d love to know what you think. There is even a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

Found in Translation

Small Hive Beetles, Arrivals and Departures

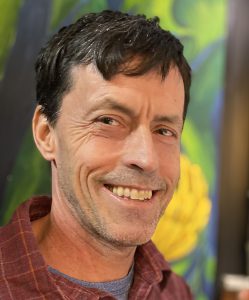

By: Jay Evans, USDA Beltsville Bee Lab

Much effort by beekeepers and scientists focuses on a few key challenges to honey bee health, from varroa and viruses to chemicals and poor queens. Small hive beetles are in the class of pests that can be devastating in certain regions and practices but are of minor importance for most of us. The biology of this species shows why it has been able to discover beehives on all beekeeping continents, while remaining an ecological and economic headache only in certain parts of its range. First, the bad news. Several new countries report the arrival of SHB annually, with India being the latest (Kumaranag, K.M., Kumar, G.P., Nithya, C., Rajendra, S.P., Rao, K.M., Kumar, D.M., Gyanudoy, D.P.P., Poonam, J., and Suroshe, S.S. First report of invasive small hive beetle, Aethina tumida Murray (Coleoptera: Nitidulidae) from India. Journal of Apicultural Research 2025, 1, 1-11, doi:10.1080/00218839.2025.2478328). Since SHB readily survive as adults for long periods without their bee hosts, they can sail on abundant container ships and make it to far-flung destinations. Since SHB were first seen outside of their native Africa in the mid 1990’s, they have become unwelcome guests in much of the beekeeping world. When the U.S. received SHB in Florida and South Carolina they received great scrutiny from officials in both states (including Florida’s then-Chief Apiarist Jerry Hayes, legendary Florida Apiary inspector Lawrence Cutts and Michael Hood in South Carolina). These officials quickly notified scientists, including a younger me, that trouble was afoot, spurring efforts to reduce the impacts of yet another pest of bees and honey. Many of us received precious samples from this growing incursion within months, while others including now-Florida Professor Jamie Ellis went directly to the source in southern Africa to investigate. Within a few years we had ample beetles throughout the eastern U.S. and reports of headaches from multiple honey producers.

Aside from their seafaring talent, SHB are prodigious spreaders once they land in a new area. Bram Cornelissen and colleagues in Europe and the U.S. carried out a clever experiment to see how hard these beetles work to locate and parasitize new beehives (Cornelissen, B., Ellis, J.D., Gort, G., Hendriks, M., van Loon, J.J.A., Stuhl, C.J., Neumann, P. The small hive beetle’s capacity to disperse over long distances by flight. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 14859, doi:10.1038/s41598-024-65434-1). First, the researchers located recipient colonies at variable distances from a central point and tried to knock down SHB populations in those colonies. Next, they let adult SHB gorge on food carrying a red dye (15,000 beetles in total) and, in a series of six trials, set these reddened beetles free. Sadly, 98% of the dye-marked beetles were never seen again. Perhaps they explored different resources, found additional hives in the area, evaded scientist eyes in subsequent colony checks, or met an untimely death. Of the 310 confirmed red subjects found in hives, about ¾ ended up in colonies closer than 100 meters from their release point, suggesting that the allure of colonies is stronger than the desire to vet distant prospects. Still, seven beetles went more than 3,000 meters from their release point within one week, with two being found in a colony 13,000 meters (8+ miles) away just a week later. Beetles were sexed before release and significantly more females found colony homes than males, suggesting either that females have better sensory skills or that males, often being less nutrition-driven, were hovering elsewhere in the environment for that first week. Work conducted early after the arrival of SHB to the U.S. supported the former, females are simply better at orienting to nests (Suazo, A., Torto, B., Teal, P. E. A. & Tumlinson, J. H. Response of the small hive beetle (Aethina tumida) to honey bee (Apis mellifera) and beehive-produced volatiles. Apidologie 2003, 34, 525–533.

Regardless of how beetles find your country and your beehive, you are probably most interested in whether they will be anything more than a skittish black mole that disappears in the blink of one’s eye. A recent survey following up on hive infestations and impacts in a long-established population from southern Italy suggests that, even for European honey bees, SHB infestations are kept in check much of the time (bee races from the original African range of SHB are notoriously good at keeping these scavengers at extremely low levels). Camilla Di Ruggiero and colleagues scanned through a few hundred Italian beehives at two seasonal time points to count beetles (Di Ruggiero, C., Gyorffy, A.; Artese, F., De Carolis, A., De Simone, A., Pietropaoli, M., Pedrelli, C., Formato, G. Environmental and colony-related factors inked to small hive beetle (Aethina tumida) infestation in Apis mellifera. Agriculture 2025, 15, doi:10.3390/agriculture15090962.). More accurately, they enlisted beekeepers to rigorously screen colonies for beetles, finding an average of slightly under one beetle per colony with a maximum of 12. This study sought to determine which factors made colonies beetle havens. Confirming early behavioral studies of hygienic bees, colonies with a high bee-to-frame ratio held significantly fewer SHB. SHB, like other scavenging parasites, thrive on quiet places to eat in peace and ultimately produce vulnerable larvae. While beetles acquire hive smells early upon entering the hive and largely pass without incident among bees, any contact with bees presents risk in terms of removal or dismemberment. Consequently, quitter colonies present less risk. Colonies in the shade harbored significantly larger beetle populations, hinting at climatic vulnerabilities in the Mediterranean area for adult or ‘wandering phase’ beetle larvae. Finally, and similarly to Varroa and other pests, the number of beetles in a colony at one survey point is a good predictor for future surveys, i.e., they are hard to shake once established.

If you are a beekeeper whose colonies or stacked frames are indeed harmed by this pest, there are excellent reviews of hive beetle control methods (most recently a paper by Julia St. Amant and Cameron Jack comparing yet-to-come to licensed treatments; St. Amant, J., Jack, C.J. Evaluating the toxicity of known western honey bee-safe insecticides in controlling small hive beetles (Aethina tumida). Diversity 2025, 17, doi:10.3390/d17040230). If you are not in that camp, give some respect when you see a rare skittering beetle. This insect achieved better living only by cracking the chemical codes inherent to surviving in a hostile bee hive. It has also traveled a long distance to see you and your bees.