Herbal medicine for bees?

Jay Evans, USDA Beltsville Bee Lab

Bees have been reliant on plants, and vice versa, for tens of millions of years. Similarly, beekeepers have known from the start of managed beekeeping that the quantity and quality of floral resources determine both the growth of their colonies and the bounty of extractable resources.

There is also a growing interest in the medicinal properties of certain plant products for bee health (and of course the health of humans and other consumers). In my world, the push for plants as bee medicines came from friends and colleagues looking at floral needs of, not honey bees but, bumble bees. Drs. Lynn Adler (University of Massachusetts) and Rebecca Irwin (North Carolina State University) are ecologists who have been on this beat for nearly two decades, looking at the costs and benefits of certain plant nectars and pollens for bumble bee health. Dr. Adler and colleagues recently published an excellent review of the history and evidence behind this thinking, describing work from their own labs and that of many others in the freely available article Understanding effects of floral products on bee parasites: Mechanisms, synergism, and ecological complexity (2022) International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife 17 244–256, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijppaw.2022.02.011.

The work with bumble bees and their natural floral resources is exciting but many of us in the honey bee world are more interested in applying this approach to a feed or forage regime that reduces the impacts of parasites and other stressors that hurt honey bees. Is there something in here for beekeepers and honey bees? As with most science, the answer is going to be ‘most likely’!

Harnessing the power of plant chemistries for honey bee health requires a grasp of 1) floral chemistries (individual molecules or the soup found in pollens and nectars), 2) bee responses to chemicals, and 3) the responses of specific bee parasites and pathogens to the same chemicals. In the paper above, the scientists do a great job of summarizing the former, pointing to dozens of studies that have determined plant contributions to bee health. These studies describe the effects of individual chemicals as well as the more typical bouquet of compounds found in even single-species nectar and pollen provisions. In a groundbreaking paper showing how plant chemicals tweak key elements of bee physiology, Wenfu Mao and colleagues showed that a few chemicals abundant in pollens can trigger both a more active immune response and a suite of proteins bees use to detoxify the pesticides they interact with (Mao, W., Schuler, M.A., Berenbaum, M.R. (2013) Honey constituents up-regulate detoxification and immunity genes in the western honey bee Apis mellifera. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am. 110, 8842–8846. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1303884110). The latter deserves its own discussion and is quite exciting, while the former provides support for the use of specific plant sources, or plant chemicals, to treat widespread disease.

In searching for plant-based cures of bee disease there are at least two camps. A more holistic approach involves choosing specific plant sources with known biological activities and then feeding bees the chemicals extracted from these plants via a solvent like alcohol or via water. Work by Claudia Pasca and colleagues highlights this approach, showing that crude plant extracts have a range of possibly interesting compounds and that such extracts from single plants or in multi-plant soups can reduce bacterial disease agents and chalkbrood outside of bees, and nosema loads when fed directly to bees (Pasca, C.; Matei, I.A., Diaconeasa, Z., Rotaru, A., Erler, S., Dezmirean, D.S. (2021) Biologically active extracts from different medicinal plants tested as potential additives against bee pathogens. Antibiotics vol. 10, 960, https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10080960). This work is mirrored by work from Paul Stamets and colleagues wherein water- or alcohol-based extracts derived from mushrooms led to reduced virus loads in bees (Extracts of polypore mushroom mycelia reduce viruses in honey bees (2018). Sci Rep 8, 13936 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32194-8) and the rich evidence that plant resins (propolis when collected by bees) contain chemicals that can reduce disease.

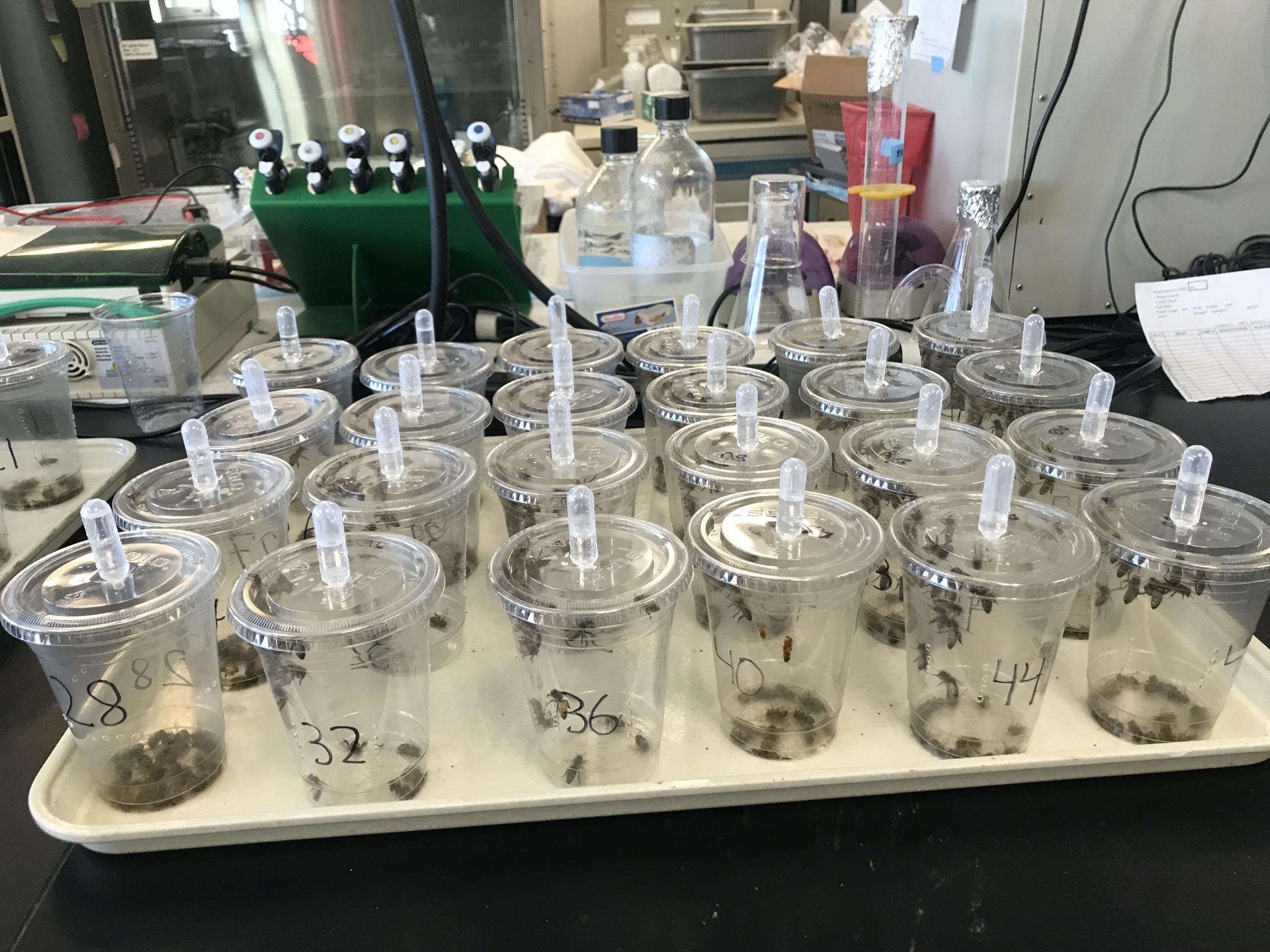

Some of us are more narrow, or perhaps less botanical, and we favor simply exposing bees and their ailments to one chemical at a time in hopes of finding a simple solution to bee disease. Our lab has tested over 100 individual plant-derived chemicals for their effects on bee viruses and, while we can’t claim to have cured viral disease on all fronts, we have found certain ones that do reduce disease levels. Dawn Boncristiani led a paper summarizing a few years of these efforts (Boncristiani, D.L., Tauber, J.P., Palmer-Young, E.C., Cao, L., Collins, W., Grubbs, K., Lopez, J.A., Meinhardt, L.W., Nguyen, V., Oh, S., Peterson, R.J., Zamora, H., Chen, Y., Evans, J.D., (2021) Impacts of diverse natural products on honey bee viral loads and health. Applied Science 11, 10732. https://doi.org/10.3390/app112210732). Even this one-chemical-at-a-time approach is a work in progress, and while some classes of chemicals appear promising across different studies it remains too early for beekeepers to buy and treat with these plant solutions.

Along with pointing the way to possible medicines, this line of work suggests that, while numerous sugar sources will suffice to boost bee energy, honey is truly the bees’ knees for bee health. Also, not all plant sources are alike and providing specific plants as nectar or pollen sources might someday be a cost-effective way to improve colony health. Can this be done at a large scale? Can more be done to help bees locate and key in on specific flowers? Will bees seek out specific plants when they have a need for medication? The latter trait, ‘self-medication,’ is known for a range of insects but the evidence that it is a widespread ability of honey bees is sparse. As a hint that bees have such abilities, Bogdan Gherman and colleagues found that bees infected with nosema favored specific nectars from a cafeteria of choices (Pathogen-associated self-medication behavior in the honey bee Apis mellifera, Behavioural and Ecological Sociobiology (2014) 68:1777–1784; DOI 10.1007/s00265-014-1786-8). How this ability translates to foraging decisions by worker bees remains unknown and other studies have not seen a similar passion for medicinal flowers when bees are infected with viruses and other threats. While an army of scientists tries to identify specific plant compounds, extracts or mixes that beekeepers might target for improved honey bee health, we have already learned much about the widespread honey bee health impacts of clean, abundant and diverse forage.