Click Here if you listened. We’re trying to gauge interest so only one question is required; however, there is a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

Found in Translation

Social Nature and the Hive Life

By: Jay Evans, USDA Beltsville Bee Lab

Picturing the Spring that will be upon the northern hemisphere when this essay is published, I feel a deep longing to see our bees in full growth, bringing back diverse pollen baskets and crops full of abundant nectar. Spring is my favorite season and it is almost painful to think of it as I write this in February (to many of us, the longest month). As a passionate beekeeping ally, I firmly believe that on the whole and in most settings honey bees are not only a tremendous asset to humans but intrinsically worthy in their own right. As messy as it might seem, this is true in both their introduced and native ranges (Eurasia and Africa for the ‘western’ honey bee).

Except for one 14 million-year old flattened specimen that fossil-hunters feel is in the genus Apis (all species of which have comb-forming, stinging, honey-storing social habits), there is no firm evidence that honey bees lived in North America before European colonists arrived a few centuries ago. Once here, however, honey bees flourished, swarming from their woven homes and making themselves an important part of both agricultural and natural habitats. In the midst of Winter, I feel the need to celebrate this flourishing.

That said, this is not another economic essay on the value of honey bee pollination or colony products, although $20-25 billion added to the U.S. economy in diverse, nutritious foods is not trivial. Nor is it another diatribe that bee-mediated pollination nourishes people throughout the world, nor that honey bees provide a cash crop for millions of families, with little startup costs, in communities that are stressed for both cash and nutritious foods.

That said, this is not another economic essay on the value of honey bee pollination or colony products, although $20-25 billion added to the U.S. economy in diverse, nutritious foods is not trivial. Nor is it another diatribe that bee-mediated pollination nourishes people throughout the world, nor that honey bees provide a cash crop for millions of families, with little startup costs, in communities that are stressed for both cash and nutritious foods.

And this is not a tribute to all the hardworking beekeepers, with from one to 80,000 colonies, who battle a variety of stresses to stay in the game (though I am not above pandering to that crowd).

It’s not even a worshipful look at how pollinators have shaped our world over 100+ million years, not simply by supporting billions of humans but in making every landscape just a bit more colorful and dynamic. This collaboration between bees and flowering plants, which started early and ended well for both, is wonderfully described by Sophie Cardinal and Bryan Danforth in their 2013 paper Bees diversified in the age of eudicots, Proceedings of the Royal Society B, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.2686. I will tackle the larger economic and environmental benefits of honey bees and other pollinators in the future, this essay is more personal.

I would argue that we socially aware humans just need honey bees beyond their great services. To me, this need comes from two drivers. First, honey bees mirror our own inescapably social natures and teach valuable lessons therein. Second, if you try even half-heartedly to place yourself in the mindset of honey bees and other pollinators you can’t escape thinking about, and striving to improve, the plant resources and the overall environment they fly over and visit on their foraging flights.

First, the social connection. It is easy to revere a species in which selfless workers provide for relatives they most likely will never meet. There are so many facets of honey bee communication, biology and nature that are mirrors for our own, leading to profoundly interesting behaviors that resonate with the good and bad of our communities. My gateway to social insects and ultimately a life studying honey bees opened with a single lecture by an ant biologist, after which I went to my dorm and decided it was inconceivable to fritter my life away without studying these special creatures who build empires largely because they choose, 90% of the time, to drop their conflicts and work for a common goal. Ignoring their preferred diets, ants and honey bees are quite similar. Most importantly, both have succeeded in no small part because they divide tasks efficiently in colonies and can thereby both out-compete their solitary neighbors and regulate their home environments. Thomas Seeley’s book The Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the Wild (2019) is a great entry into the wonder of bee inner worlds, while German professor Suzanne Foitzik shares similar life stories for ants in her 2021 book Empire of Ants: The Hidden Worlds and Extraordinary Lives of Earth’s Tiny Conquerors. In my case, the itch to learn about social insects became a full-on rash after opening a small student beehive for the first time while devouring the many stories of how honey bees and humans have been partners for thousands of years. From “busy as a bee” to “dance language” and “guard bees”, how we think of bee societies is hard to decouple from how we view our own. Not surprisingly then, neither bee nor human societies are perfect. Both show conflict within, vulnerabilities to parasites of all sorts and an occasional tendency to trample other beings, but both are marvels to behold, and exhilarating to compare and contrast.

First, the social connection. It is easy to revere a species in which selfless workers provide for relatives they most likely will never meet. There are so many facets of honey bee communication, biology and nature that are mirrors for our own, leading to profoundly interesting behaviors that resonate with the good and bad of our communities. My gateway to social insects and ultimately a life studying honey bees opened with a single lecture by an ant biologist, after which I went to my dorm and decided it was inconceivable to fritter my life away without studying these special creatures who build empires largely because they choose, 90% of the time, to drop their conflicts and work for a common goal. Ignoring their preferred diets, ants and honey bees are quite similar. Most importantly, both have succeeded in no small part because they divide tasks efficiently in colonies and can thereby both out-compete their solitary neighbors and regulate their home environments. Thomas Seeley’s book The Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the Wild (2019) is a great entry into the wonder of bee inner worlds, while German professor Suzanne Foitzik shares similar life stories for ants in her 2021 book Empire of Ants: The Hidden Worlds and Extraordinary Lives of Earth’s Tiny Conquerors. In my case, the itch to learn about social insects became a full-on rash after opening a small student beehive for the first time while devouring the many stories of how honey bees and humans have been partners for thousands of years. From “busy as a bee” to “dance language” and “guard bees”, how we think of bee societies is hard to decouple from how we view our own. Not surprisingly then, neither bee nor human societies are perfect. Both show conflict within, vulnerabilities to parasites of all sorts and an occasional tendency to trample other beings, but both are marvels to behold, and exhilarating to compare and contrast.

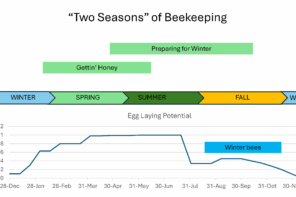

A second preeminent reason to value honey bees is that they truly provide a gateway to understanding nature. When beekeepers see their bees exit the hive, circle-wave their home and sail off, they marvel at what that tiny bee will see on a journey across the landscape, wishing the bee luck and the memory cells to return after a successful foraging trip. This care for one’s bees inevitably leads to a greater appreciation for the flowering world, leading beekeepers to seek ways to improve and diversify the green world their bees encounter. Beekeepers fret over, and are noisy about, any ill winds that arise from degraded environments within two miles of the colonies they host. Habitat loss, climate, land practices and disease all impact the health of honey bee colonies, and beekeeping forces us to learn about each of those topics. Every beekeeper also has a keen sense of weather and the seasons. Okay, the same is true for gardeners, birders and hunters… and by some stretch of the imagination even golfers, although better if they let their ‘greens’ revert to wildflowers. Similarly, beekeepers are among the most knowledgeable humans with respect to how diseases spread, how to slow infections, and when it’s time to seek a doc, even if we neglect that knowledge sometimes with our own health and that of our colonies.

It’s not an easy path, and beekeepers often stumble. But, bees and beekeeping give back incredible riches to those who listen to the buzz and hitch a ride with their bee teachers. Hope springs eternal and here’s hoping your Spring is bountiful.