What’s true and what’s just a story?

By: Robert Least

Curious, quaint and amusing describe our reactions to the following anecdotes. Lest one should feel superior in 2016 to these old tales, one should not forget that if we had lived during those times we might have believed the same things.

Ever since honey bees were used by man, they have been misunderstood and mischaracterized. Wild speculations and conclusions abounded with little to no regard to critical analysis; believing the queen to be a king; calling bee larvae grubs, worms, caterpillars and maggots; banging on pots and pans to make swarms alight; calling bees honey-flies. Native American Indians called the settler’s honey bees White Man’s Flies and J. Swammerdam in 1737 colorfully labelled the wax moth as the Bee Wolf.

Anthropomorphism: Assigning human emotions and traits to other living things. Before science and careful observation became the norm, beekeepers used fanciful and creative imagination to express the behavior of the honey bee. Note the following examples:

Fable or fact? Folklore of 19th century England and America in parts of the South, relates that mourners at funerals would rap on hives to inform the bees of the death of a family member. Some even dressed their hives in funeral garb to pacify the bees. People noticed that bees would take the loss at heart and would alight on coffins in respect, but little did they realize that the bees were merely securing varnish, or resin, from the coffins, not mourning the deceased.

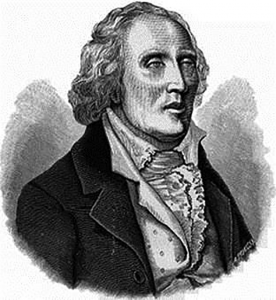

Queens, especially, were given over to fanciful flights of imagination. Xenophon, a Greek general and historian in 400 B.C. wrote, “While she stays in the hive, she does not allow the bees to get lazy, but sends out those who have to work outside, observes what they bring in; takes it and stores it until it can be used . . .Further she supervises the building of combs in the hive and sees to it that they are constructed well and pretty and that the brood is reared in an orderly way” (Root 1). In 1901, Maurice Maeterlinck (2) offered this imaginary account of swarming bees: “The bees, when they find the queen has not followed them will return to the hive, and scold the unfortunate prisoner, hustle and ill-treat her accusing her of laziness, probably, or suspecting her of feeble mind.”

Maeterlinck continues: “. . . when a virgin queen is performing the perilous ceremony known as the ‘nuptial flight’ . . . her subjects are so fearful of losing her that they will accompany her on this tragic and distant quest of love – when the young queen sallies forth in quest of her lover they will accompany her – eager as they form closely around her, and shelter her beneath their myriad devoted wings.”

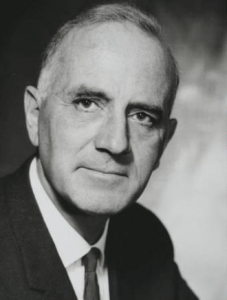

L.L.Langstroth (3) speaks of Her Royal Highness: “Among the bees the good mother is the honored queen of her happy family; they await upon her steps with unbounded reverence – until in short do all they can to make her perfectly happy.”

Swarms galore. J. Swammerdam (4) in the 18th century, cited a hive that issued multiple swarms and those swarms in turn swarmed again and again, producing no less than 30 colonies in a single season. I doubt it. Colonies typically issue a single, or prime swarm, sometimes followed by one or two smaller, after swarms. However, Africanized colonies may swarm or abscond.

Peculiar matings. In 1678, M. Rusden (5) stated, “And if the bees do breed without copulation . . . it can be no otherwise but by the wind . . .” J. Swammerdam (4) of Holland, the Netherlands, wrote in 1737 that the queen is impregnated by the peculiar and unpleasant odor – “odiferous effluvia” – that is produced by the seminal effusion of many drones when they are confined in a small space.

R.A. Reaumur (6) of France stated in 1744 that he thought matings to occur within the hive. A Mr. J.S. Davitte of Georgia claimed to have mated many queens in a large, circular tent with free flying drones; others have tried matings in greenhouses and boxes. In the mid-1800s, some claimed to have hand-mated queens with success. I have hand-mated several different species of giant silk moths, obtaining hybrids that would have been impossible to obtain through natural matings, but I doubt it will work using honey bees.

In 1815, R. Huish (7) said that after queens laid eggs in the cells they were then fertilized by drones. He reasoned since that there were no drones in the early part of the year to mate with queens, they, the queens, laid eggs in the late Fall, which remained dormant all Winter and then hatched in early Spring.

In 1855, Dr. Donhoff of Germany reported that he took a drone egg from its cell and artificially fertilized it and it became a worker. I passed this on to renowned bee inseminator expert Susan Cobey. She stated that it did not likely happen, given the state of the art at that time.

The great unwashed. “Those who belong to the family of ‘the great unwashed’ will find to their cost that bees are have a special dislike to those persons who are not cleanly . . . and that unpleasant ones (odors) are very apt to excite their anger” (L.L. Langstroth 3). He notes that bees have acute olfactory senses which cause some members to threaten and sting those with offensive odors, especially the “great unwashed.” Albert J. Cook (8) contradicts himself in rapid succession: “The common belief, too, that some persons are more liable to attack than others is, I think, erroneous.” He continues, “Occasionally a person may have a peculiar odor about his person that angers bees and invites their darting tilts, with drawn swords, venom-tipped . . .”

“I am never afraid that a healthy bee will attack me unless it is unusually provoked. And I am almost sure as I hear one singing about my ears that it is diseased” (Langstroth 3). He was advised to render painless a bee sting by deliberately making another bee sting the same spot as the first, which he did. The hapless Rev. found, to his dismay, that far from alleviating the pain, it doubled it! A shot of poisonous venom times two!

Hissy fits. Langstroth continues, “A word now to those timid females who are almost ready to faint or to go into histeries (sic) if a bee enters the house or approaches them in in the garden or fields. Such alarm is entirely uncalled for.” Feminists today might call that sexist.

An article in the March 5, 2016 Des Moines Register reports that beekeeper Deb Willard says that bees generally leave humans alone unless their queen or hive are threatened. This seems like comparing bees surrounding and protecting their queen to Secret Service agents surrounding and protecting the U.S. president.

I recall that on a trip to Rocky Point of Baja California rains produced puddles everywhere, producing myriads, yes billions, of mosquitoes in this desert coast. Enormous numbers buzzed on our trailer’s windows trying to gain access which looked like an episode of the TV program Twilight Zone. When we stepped outside, tens of hundreds of mosquitoes began their blood sucking all over our white, delicate bodies, but the native Mexicans standing right next to us had nary a mosquito on them. It may be that bees are attracted to sting those with unique body odors.

Emotional highs. A beekeeper in days of yore, wrote that newly emerging workers were an occasion of joy and excitement to the older workers. Nothing could be farther from the truth, as these young ones are jostled and pushed aside because they are apparently in the way of their busy, older sisters. A Mr. Wildman, of pre-1850, said he witnessed newly hatched workers gathering pollen and honey the same day they emerged from their cells. A tall tale. These babies do very little for their first three days but after the third day they clean cells and by the sixth day their nursing glands kick in and they begin to feed larvae.

A blind, Swiss apiarian, Francois Huber (9) in 1814, stated that when a queen emerges the bees are thrown into a joyous excitement, so much that he noticed a rise in temperature from 94°F to 105°F.

When bees are deprived of their queen the Rev. Langstroth pondered: “How do they first become aware of it? Perhaps some dutiful bee feels that it is a long time since it has seen its mother, and anxious to embrace her, makes a diligent search for her through the hive! . . . and by their the most impassioned demonstrations manifesting their agony and despair.” Nothing at that time was known of the queen substance, also known as queen retinue pheromone, or technically € – 9 -oxodec -2 -enoic acid. This chemical queen substance is transmitted from one worker to the next throughout the colony to “inform” them of the presence or absence of their queen, and they behave accordingly.

Get out the shotgun. Overstocking occurs when too many hives are placed in a given location. Trouble brews when a beekeeper sets many colonies directly on the same location already occupied by another. An example of limited acreage are the fields of lavender in Oregon and Washington, or maybe fields of buckwheat in Pennsylvania. There is nothing finer than delectable, delicious, lavender honey. But should some beekeeper set up hives when others already have been in place in these cultivated acreages, the original tenant beekeeper would rightfully be upset. The 1940 edition of The ABC and XYZ of Bee Culture, Root (1) stated: “Mr. Newcomer should not attempt to crowd in, for he may find some one (sic) beekeeper who will get ‘sore’ and resort to the shotgun argument.” In that edition under Enemies of Bees it is stated “…in large queen rearing yards there is quite likely to be a loss of young queens if birds are allowed to go unmolested – the owner of a queen-yard would do well to use his shotgun until everything in the way of bee-killing birds is destroyed.” This recommendation – killing birds – was repeated verbatim in the 1972 edition. The Rev. Langstroth (6) wisely spoke against killing birds: “. . . I have never yet been willing to destroy a bird because of its fondness for bees; and I advise all lovers of bees to have nothing to do with such foolish practices.” A further word to the wise: it is illegal to kill song birds.

An extravagant claim. Colin G. Butler (10) in 1954 wrote, “It has been stated by a number of writers that worker honey bees can fly at what seems to be quite fantastic speeds; some of the most extravagant estimates exceed one hundred miles an hour.” One might wonder how this was actually measured. What are the parameters of typical flight speeds? O.W. Park (11) stated the normal flight speed to be 10 to 15 mph with a maximum flight speed approximating 25.5 miles per hour, recorded for both outgoing and incoming bees.

How far will bees fly to reach nectar sources? It is remarkable that in 1927-1930 J.E. Eckert (12) recorded bees flying eight to 8.5 miles to reach flora and weight gains were recorded for bees flying five miles to forage areas. Cook (8) reported that marked bees flew 2½ miles, unloaded and returned in 30 minutes. Prevailing winds can effect the speed and duration of flights. Typically, bees range no further than necessary and flights of two or 2½ miles, or further, are probably made because nearby sources are poor or unavailable. This can be good news for those beekeepers surrounded by intensive agriculture. If a town is two miles distant from their beehives the bees can forage among the numerous and varied city grown flowers and trees.

In the 1800s, many beekeepers placed rye or wheat flour in trays outside the hives which the bees would collect until natural pollen became available. Because the bees seemed eager to collect the flour it was assumed that it was good for them. In fact, Langstroth actually poured flour into empty combs to save the bees the time and energy from gathering it. It was not known at the time that flour didn’t provide the varied and necessary proteins and amino acids for larval development. Moreover, during a dearth of natural pollen, bees will collect all sorts of fine particles, such as coal dust, sawdust, fine particles of cement, powdered chicken and horse feed, and even dry, black earth. No doubt, they would eventually clean house of this worthless ruble, including flour.

Mad Honey. This dark, reddish honey is called “mad’ because it can produce hallucinations when eaten. Bees gather the nectar from Rhododendron species ponticum and luteum which contain a neurotoxin called grayonotoxin. This evergreen shrub grows on the mountain sides of the Black Sea region of Turkey. Mad honey is also known by the locals as “deli bal” which they consume for its medicinal benefits, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus and some stomach diseases as well as its “value” of producing psychedelic optical illusions. When tasted, it produces a burning sensation in the throat, and eating more than a teaspoon can produce low blood pressure, irregular heartbeats, numbness, blurred vision, fainting, nausea, but rarely death. It was used by Roman and Greek warriors centuries ago as a weapon of war, making it available to their enemies as food (Xenophon 1). Today, mountain people in Nepal, using long poles and baskets, rob what they call Red Honey or Crazy Honey from the cliff dwelling honey bee Apis dorsata. They eat this honey for its hallucination effect. This honey is also derived from Rhododendron species.

This is no exaggeration: Edible honey was discovered in the sepulcher of Egyptian King Tutankhamen, aka King Tut’s tomb, after having been buried there for 3,300 years. It seems that as long as stored honey is sealed and strictly kept from absorbing moisture in the air, it can be preserved indefinitely. Burying the deceased nobility with the embalming properties of honey was a common practice at that time. The Egyptians also placed bees and honey in tombs as an offering to the spirits and the dead (Root 1).

Apiarian science today continues to unravel the mysteries of the honey bee, and disproves, one by one, the myriad of homespun “theories” and fanciful tales of this most fascinating insect. The quest for unravelling the ever changing dynamics of this living organism, with its ever emerging questions and problems, goes on and on.

References

Root, A.I. 1972. The ABC and XYZ of bee culture. The A.I. Root Co. Medina, OH.

Maeterlinck, Maurice. 1901. The life of the bee. Dodd, Mead and Co. Cambridge. MA.

Langstroth, L .L. 1853. The hive and the honeybee. Greenfield, MA.

Swammerdam, J. 1737. Biblia naturae. Leyden, South Holland, Netherlands.

Rusden, M. 1679. A further discussion of bees. London.

Reaumur, R.A. 1740. Memoires pour servie a l’histoire des insects.

Huish, R. 1815. A treatise on the nature, economy and practical management of bees. London.

Cook, A.J. 1902. Beekeepers guide: manual of the apiary. George W. York Co. Chicago, Ill.

Huber, F. 1814. Nouvelles observations sur les abeilles 1 & 2, translation 1926. Dadant, C.P. Hamilton, Ill.

Butler, Colin G. 1954. The world of the honeybee. London.11 Park, O.W. 1923. American bee journal: 63-71. Hamilton, Ill.

Park, O.W. 1923. American bee journal: 63-71. Hamilton, Ill.

Eckert, J. E. 1933. Journal of agricultural research.

I wish to thank Janine Weast Searcy for proofreading the text.