Find me online!

www.twitter.com/tonibee

www.citybees.blogshop.com

By: Toni Burnham

Marina Marchese

When she was born, Marina Marchese must have entered the world taste buds first, because that is the way in which she entered the world of bees and honey, and how she hopes to help you understand it, too.

Marina is an author (Honeybee: Lessons from An Accidental Beekeeper, and co-author with Kim Flottum of The Honey Connoisseur: Selecting, Tasting, and Pairing Honey), designer, trained expert in the sensory analysis of honey, and founder of the American Honey Tasting Society. Every year she trains beekeepers in tasting and evaluating their products, and to see the world of honey through a new lens. She is a honey sommelier, an expert in tastes and pairings and beautiful experiences only available through the shared work of human and bee.

“You have got celebrity chefs on TV in the news, going to farms. Picking out their own vegetables, visiting slaughterhouses, picking out organic grass-fed this and that, and they’ve got their favorite beekeeper! We’re in a food renaissance where the chef and the restaurants are king. Why wouldn’t beekeepers want to make that connection with the consumer and the foodie and the chef and be able to talk that language with the chef and say, ‘the honey is very light, it’s got a very fruity butterscotch nifty note?’ Why wouldn’t beekeepers want to make that connection? It is only to their benefit!”

“I have been a beekeeper for 17 years and I kind of straddle the line between beekeeping and food, and from what I see it is kind of a unique position”

“You’ve got all these really great beekeepers that are producing really excellent honeys, but I find that many really don’t know enough about honey as a food, as a flavor. That’s where I straddle the line in knowing about bees and about floral sources, but I’m a foodie at heart.”

“You’ve got all these really great beekeepers that are producing really excellent honeys, but I find that many really don’t know enough about honey as a food, as a flavor. That’s where I straddle the line in knowing about bees and about floral sources, but I’m a foodie at heart.”

“I went through all the steps of learning beekeeping: managing pests and diseases, splits and swarms, and so on. Coming from the arts, as well, I was of course really excited and interested in beeswax and in crafting skin care products and candles. But honey is truly what most intrigued me early on.”

“And then I couldn’t find any information about it! That search is what led to writing The Honey Connoisseur. In fact, however, that book was written before the first book I published, Honeybee: Lessons from and Accidental Beekeeper.”

“Back in 2003, I went to the National Honey Show in London seeking information, and was disappointed that beekeepers were passionate about honey as a food, and interested in being discoverers of flavors and matching flowers to flavors. It became my passion, and my mission to figure this out.”

“I wanted to come to some sort of understanding, to find a resource, a database, to answer the question of ‘Where’s that information?’ Well, it didn’t exist. After the honey show, I did extensive research on Eva Crane: she wrote a lot about honey and was probably the most prolific writer on the subject. But she never talked about flavor!”

“I turned to the research of Jonathan White of the FDA, who wrote hundreds of papers on honey in the 1950s and 1960s, but who again did not address this concept of flavors and flowers, and where to find them and what they taste like.”

“That’s what led me to Italy, where I stumbled upon a class that they were doing on honey. Early on, I saw that it paralleled the appreciation of wine. I’m a wine person, I’m Italian, I’m a foodie: I grow food, I cook food, this is where my head is. I was very excited. I thought, ‘Maybe this is a new road where I can see what’s happening.’”

“That’s what led me to Italy, where I stumbled upon a class that they were doing on honey. Early on, I saw that it paralleled the appreciation of wine. I’m a wine person, I’m Italian, I’m a foodie: I grow food, I cook food, this is where my head is. I was very excited. I thought, ‘Maybe this is a new road where I can see what’s happening.’”

“In these tiny local shops in these small medieval towns, they would sell honey alongside the olive oil and wine. That’s something that would never happen in the U.S. You would never go out to buy a bottle of wine in the United States, and ‘Oh! By the way, get some olive oil and honey.’ That just doesn’t happen here.”

Why not in the U.S.?

“Remember, we are talking about local, small batch beekeeper honey. We are not talking about commercial honey, which is completely different. I think you can, though education, change beekeepers’ approach because what they are producing is gold! Though many complain that they can’t compete with $3 Chinese honey in the plastic teddy bear, all you have to do is put yours side by side.”

“You don’t have to be an expert to taste the difference between beekeeper honey and commercial honey. And you know, beekeepers need to be able to talk about honey and to explain the floral sources and the seasonality of it to the consumer, and just let them taste it side by side. If that person doesn’t want to spend $10 or $12 dollars on your honey, they aren’t your customer. You have to go to where the people are foodies, people that are interested in quality.”

In cities, yes, or online?

“That may be part of it, I think. Beekeepers that are not in affluent areas may not think that they can get that premium. Beekeepers may have to think outside of the box, be innovative and put up a web site. To learn how to market and sell their honey, to package and ship it. To reach out to chefs and to gourmet shops in their area. If you want to get in the trade of selling honey, you will have to learn some of the business side. I understand that many beekeepers see themselves primarily as farmers or hobbyists, not business managers, so it can be a decision about whether you are in it for fun or also for money.”

“All of this is based upon the training that I had in Italy. It is mind boggling what they have done: they have picked apart honey in the manner that we have used to talk about coffee, tea, or chocolate. They are 30 years ahead of us in evaluating honey, taking it to the point where you can look at a honey and taste it blindly and be able to identify it.”

“I don’t think here in the US that people yet understand the depth and the breadth of the evaluation process for honey. You need to sit in a class, or sit yourself down and learn this stuff. I offered this just recently at EAS in Delaware (2017). We had 20 people signed up, and then they asked for a second talk. There was a waiting list for the first one, and then a waiting list again, but we were out of time and could not do anymore!”

“[During the classes,] People sit in and find it incredible to see just how much there is to know about honey that has either been lost or not developed here. We have a lot of work to do. Beekeepers can learn a lot to create a better product and market it, and to connect consumers in a more intelligent way.”

Honey judging is not honey tasting

I know that there is a honey judging culture in the US, and I did go to the University of Georgia to take the beginning of the Honey Judging Class. I was a little bit disappointed because I came from a place of food, and there is not a lot of emphasis on flavor. The judging tends to be much more about preparation for the bench. You know, you can’t have fingerprints on your jar…”

“I was to judge the Black Jar Contest at EAS. You don’t have to be trained judge (though I am a trained judge in Italy–they do it very differently). I tasted about 30 honeys, and some were really good and some were not. We took notes. I felt like the honeys in which I was able to taste a defect–like those that were overheated or had rust or grit in them – perhaps my tasting notes were really going nowhere unless I could actually help the beekeeper? Like there were a couple of samples where I said, ‘I would like to sit down with the beekeeper and talk to them, to help them to make a better product for next year.’”

“Next to me some other judges were evaluating a frame of honey comb, and it was a poor-quality sample. They took their notes, they critiqued it, but the only way that that beekeeper is going to learn is if the educated, trained judge can sit down with them and say, ‘this is what we look for, this is what you need to do, this is what went wrong, this is what the bees did not do, and next time it should look like this.’”

“The judging protocol in the US is established, extending back to Roger Morse in the 1940s, but in the future, we, as a country and a culture, could go more deeply into this food renaissance: honey has got to catch up! . . . Now, honey is judged light, medium, and dark. But in the “Light” category, for example, you are going to have things like a Black Locust or a clover honey, which are different. In my mind, and as I was trained in Italy, you are judging apples against oranges. How can you do that? They are both going to be light honeys, but they have different flavor. They don’t belong in the same category.”

“Talking about the dark categories: if you are submitting honey in the category of the dark ambers, you are going to have things like buckwheat and avocado, maybe Tulip Poplar, maybe bamboo. If you have got those four very different dark honeys, you can bet your bottom dollar that buckwheat is going to lose, because that honey is going to split the room! Some love it, some hate it. Then you have avocado, which is very dark, and a very bitter honey. On the other hand, everybody is going to love Tulip Poplar and red bamboo honey, which are also dark. It doesn’t make sense–in my brain – how we can judge honey by color. You should be judging by floral source or flavor.”

“I want to repeat: I am not criticizing, just a little confused. It doesn’t make sense in my head to judge by color or even by region. Here in New England, we have like five different honeys, and they go from very very light to very, very dark. Many variations of medium! If you are going to judge honey by this region, you are going to have Black Locust, which is extremely light, compared to buckwheat, which is really really dark. There will be medium, middle, super floral with earthy malty tones, all in the same category. We have such a diversity of flavors AND colors, so it is really going to be a personal opinion if you are going to judge honey by region.”

“We have also not done the work here on how honey conforms to particular floral sources – meaning, nobody has done the complete pollen and chemical analysis of enough samples of any particular honey to be able to definitively say ‘This is goldenrod honey’ or ‘this is orange blossom honey.’ In Italy, we were trained on almost 50 different honeys. Once you have that training you know what this floral source honey should taste like. You have a database in your mind and in your nose that you can take to other honeys.”

I am doing classes about twice a year…but we also do like a newsletter and we reach out to the mead people and the food industry. We’ve had people come from all over the country, and we’ve had people come to our classes from Canada and Mexico.”

What happens in class?

When we talk about tasting honey, we start even before actually tasting it. We talk about how we taste: how to use your nose, and your tongue. We teach them the psychology and the physiology of tasting: ‘What is the difference between taste and flavor?’ And there is a difference!”

“Without going into a million details, we also teach the psychology of tasting: how your body reacts to smells and flavors. There are tasting exercises, some smelling exercises. Then we present the group with 12 honeys from known floral sources. We teach them the methods of evaluation: visually, then we do aroma, then flavor, then texture. We walk through a method for sort of a schedule, a process of how to evaluate honey.”

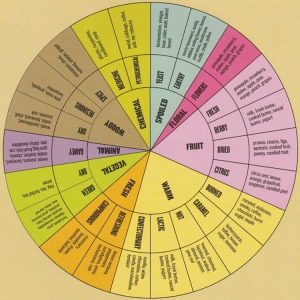

Like the Tasting Wheel that breaks out a wider vocabulary and set of concepts for tasting and comparing honeys!

I search online for samples to use for my classes, and I come across some very interesting floral sources. Then when I try to get a description, the beekeepers just say things like “it is delicious” or “it is surprising.” They have no vocabulary, and that is where the honey wheel comes in, to teach them how to talk other than saying ‘It’s good.’ Or ‘sweet.’ Or ‘delicious.’”

I search online for samples to use for my classes, and I come across some very interesting floral sources. Then when I try to get a description, the beekeepers just say things like “it is delicious” or “it is surprising.” They have no vocabulary, and that is where the honey wheel comes in, to teach them how to talk other than saying ‘It’s good.’ Or ‘sweet.’ Or ‘delicious.’”

“I’ve had the opportunity to taste some honeys that literally taste like licking an ash tray, or the most sweet-fruitiest-lightest. For me, every honey has a story, every honey has a value, every floral source has a story about that region, the flower itself, even the beekeeper comes into play as part of the story of the honey”

“But you know, honey still needs to get a little bit more respect in the culinary world. Honey is more complex to produce than wine and olive oil.”

If we don’t respect it, they don’t respect it.

“Exactly. As more people get interested in a protocol for sensory evaluation of honey, we are going to get more respect. You meet people who say, ‘I don’t like honey’ and the first question I have is ‘what kind of honey did you have?’ ‘Oh, I had the teddy bear in the grocery store.’ You must immediately be able to whip out a bottle of honey, no matter where it is from, and let them taste it. Most of the time they say, ‘Hah! I do like honey!’”

“People just need to know about good honey. They just need to know.”

Toni Burnham lives and keeps her bees on roof tops in Washington, DC. She is one of Bee Culture’s regular contributors.