Apiary Hygiene!

Find me online!

www.twitter.com/tonibee

www.citybees.blogshop.com

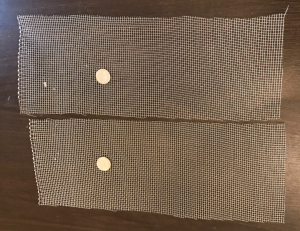

At this month’s club meeting, we handed out 6” by 16” rectangles of eight-to-the-inch hardware cloth to any member who wanted one, and offered a short demo on how to turn it into the world’s simplest robbing screen. Our club paid for the hardware cloth (and sacrificed about 10 minutes of keynote speaker time) to do this. But it was worth it to us: robbing screens could potentially help in the selection of better urban bees, if you squint a little and look to the side, perhaps.

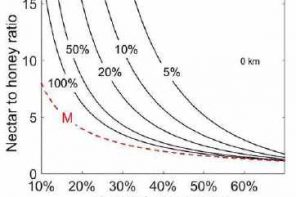

For background, a robbing screen is a device that attempts to separate the flight of robbing bees from colony residents. Using a mesh too fine for bees to pass through, the beekeeper makes a screen that allows the smell of hive resources to attract robbers to the front of a hive, while providing reduced, indirect entry to residents which instead follow the pheromone trails of fellow colony members in and out of the hive. I usually pair such a screen with a reduced entrance to make colonies more easily defended.

Sometimes, the comparisons between colonies of bees and communities of people are irresistible, though not always helpfully so. My story of urban beekeeping over the past 12 years sounds a bit like urbanization itself: you start off kind of on your own, exploiting lots of resources and with little exposure to the consequences of others’ experiences and actions. Flash forward a decade or more, and you are sharing habitat with hundreds of others, swapping individual organic material with gusto, and facing a higher risk of home invasion.

Yes, my friends, this article is about how the very well known, just about universal phenomenon of robbing is somehow different in the city. If you want to skip to the pictures, here’s the heart of it:

robbing is becoming part of the urban beekeeping furniture with densely packed colonies and wide differences in strength;

it creates another obstacle to colony survival, one which is not necessarily linked to the quality of the winner’s genes; and

it may not be hard to slow robbing down, if not stop it, in your own city apiary.

So why discuss robbing now? On March 8, Dr. Dewey Caron gave a terrific talk to the Northern Virginia Beekeepers Association that both inspired, and (as usual) kind of terrified me. Dr. Caron had much more to share than what I am misinterpreting here, but his words on sustainable beekeeping and breeding from survivors as a critical tool seemed like a hard prescription for urban beekeeping. It is clearly the only way that evolution and hybridization–the quest for the perfect bee–can work. Where I keep bees, however, the reasons your bees have died can range from standard issue beekeeper error to bad weather to mosquito spraying to having pseudo-beekeeper neighbors (among others). Therefore, even though I would like to believe that the survivors from which we might breed have thrived due to an internal quality that might also help others pull through, it might just be because they were spared living next to the Typhoid Mary of unmaintained downtown colonies.

Like anywhere else, city beekeepers can have bees die because they really should have: for instance, they were bred for Nebraska or Florida winters and you live in New Jersey; the queen was a bum (come on, she has one job, you know?); they were left to swarm over and over; Varroa mite levels spiked unaddressed, and so on. There are steps any of us could have taken in these cases: purchase or breed local queens, monitor colonies more closely when a new queen is introduced, have and execute a detailed IPM regimen, regularly test and (if necessary) treat for mites.

There are hive losses that just shouldn’t happen, however, if it is just about the quality of the genes. Bees killed by pesticides, unpredictable forage due to climate shifts, bees crossing paths and passing pathogens new and old more frequently, Varroa bombs rolling like waves across neighborhoods. In this town, we are starting to see a related harsh inevitability by midsummer: robbing creates and exacerbates hive losses, unrelated and unstopped by beneficial genetics that give us cool things like mite resistance, adaptation to local climate, wintering, and productivity. In other words, you could be breeding wonderful survivor bees, and lose them without knowing you had them, if robbing peaks across your neighborhood and blows through your yard.

The reason we hand out robbing screen materials in May is that robbing is a given for us in August. We always have dearth soon after our one and only big nectar flow. At that point, our colonies are at peak population, and then nature slams on the brakes. Beekeepers must do something about it, or lose at least some bees (and possibly create a public hazard).

Among my colonies, the Carniolan hybrids seem to look around during dearth, say “Winter is coming!” then start rolling back the brood rearing. They are clued-in to seasonal shifts. For my Italians, however, the party never stops. They want babies, they want them now and always, and they need that stuff that they smell in that super pronto. When my Carnies make the seasonally adapted shift to smaller colony size, they become vulnerable to genetics that come from a sunny ancestry where winter didn’t really come, or come for long.

In this case, I can have a colony of bees that are poorly adapted for my winters rob out a colony that has a much bigger clue. This is not a genetic step forward. Also, all that crazy brood rearing is like a hothouse for varroa mites. So robbing gives advantage to the wintering genes I would not choose, and passes around the greatest threat my bees face.

It’s not that the Italians do not have traits I want to keep: I love the gentleness, the productivity, the reluctance to swarm (compared to Carnies). What if I just made it harder for my bees to rob each other? What if my neighbors did that, too? What if we made it easier to keep the good stuff, hold off the bad, and end up with a much better idea of what killed the colonies that died and confidence that the ones from which we breed deserve to be carrying the torch forward?

Since robbing can get exponential once it starts, wouldn’t even small barriers and delays help? Here’s one way to make cheap and easy robbing screens. They are not as failsafe as some of the store bought or more complex ones, but will probably help robbing not start as easily or as soon. Screens for most other hives can be cut down from the measurements below.

To make a simple robbing screen for a 10-frame Langstroth hive

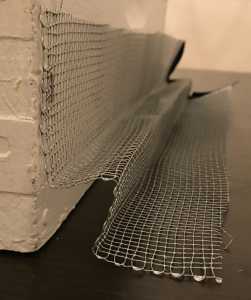

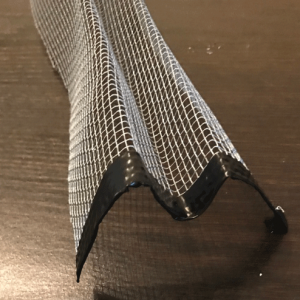

This is not beautiful or guaranteed to prevent robbing, but it is cheap and quick. This asks for #8 hardware cloth, but you can use metal window screening. One British beekeeper worried about the sharp edges demonstrated how to wrap the edges in tape for their protection (see final photo).

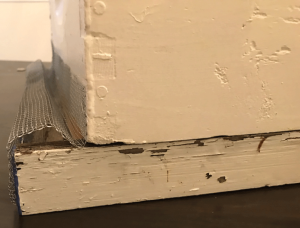

Determine whether your bottom board has one of the two profiles:

- Side bars that extend to the end of the landing board; or

- Side bars that end flush to the face of the hive body with the landing board extending forward

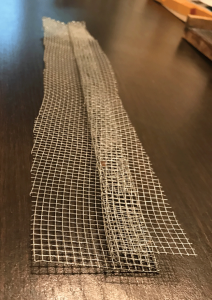

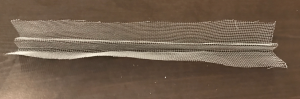

Using good quality tin snips, cut a roughly 16” by 6” rectangle of #8 (8 squares to the inch) hardware cloth – more info at the always wonderful HoneyBeeSuite. https://honeybeesuite.com/what-size-hardware-cloth-is-best-for-beehives/

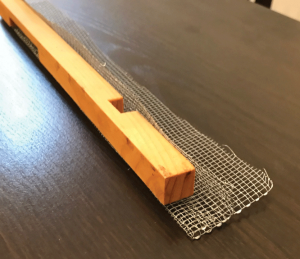

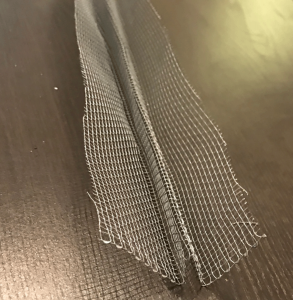

If you have a wooden entrance reducer, you can use it during the following steps to help fold straight lines and determine passage size.

Using the entrance reducer lined up with the folded edge, make another 90° fold. The entrance reducer ensures that you are leaving enough space for bees to pass through.

After this, there are two alternatives.

Bottom Board A Instructions:

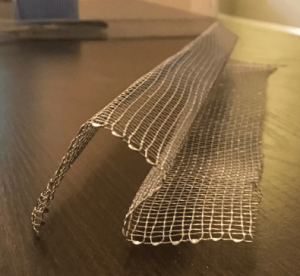

If your bottom board has arms that extend to the edge of the landing board (A), fold the other side over the fold you just made. Then spread it out.

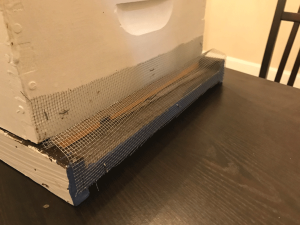

To install:

Place the entrance reducer first: I use the larger opening if no robbing has occurred yet, the smaller opening if there have been reports.

Have either a staple gun or tacks available to secure the screen.

The “P” basically goes in upside down. The leg of the P will be flat on the face of the bottom box. The next fold will make a tent over the side bars, the final fold will go over the front of the bottom board. Place a staple or a tack in the center and at both ends of both the top and bottom of the screen.

Bottom Board B Instructions:

If your bottom board arms that support the boxes end at the front of the box (B), flip the hardware cloth which has been folded in half and then folded again over. Fold the second side to match the first.

I call this the W fold.

Spread this out some, then align one of the bottoms of the V to the edge above the entrance reducer, and attach with either staples or tacks. Extend the other V-fold so that the middle fold makes a right angle. Attach the remaining flap of hardware cloth to the landing board.

Toni Burnham lives and keeps her bees on rooftops in Washington, DC.