By: Mark Winston

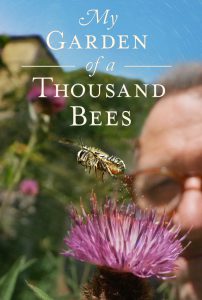

The video documentary My Garden of a Thousand Bees is, quite simply, a spectacular film, replete with jaw-dropping visuals depicting a microcosm of wild bee natural history found in an urban backyard in Bristol, England.

The video documentary My Garden of a Thousand Bees is, quite simply, a spectacular film, replete with jaw-dropping visuals depicting a microcosm of wild bee natural history found in an urban backyard in Bristol, England.

My Garden was filmed by Martin Dohrn, an experienced filmmaker with 30 years of nature documentaries under his belt. He found himself isolating at home when the British government implemented their March 2020 COVID-19 lockdown. Most of us in similar situations took up sourdough bread baking, musical instruments, paint-by-number canvases and elaborate jigsaw puzzles, in between binge-watching streaming television channels. Dohrn took a different path; he went outside to the unkempt, messy mix of meadow and hedges in the tiny yard outside his townhouse and began filming.

The result is astonishing, but don’t just take my word for it. My Garden has been highly rewarded with awards, winning four at the Wildscreen Panda Awards including the Golden Panda for best natural world storytelling. It’s also won two awards at the Jackson Wild for best onscreen personality (likely for Dohrn, who is quite engaging, but possibly for the bees themselves) and for cinematography, and been nominated for four Grierson Awards and an Emmy.

Filming bees is not a trivial task; they are small and fast, moving in and out of focus quickly and unpredictably. Dohrn had to devise game-changing techniques in low-light and macro filming, using a device he called the Frankencam that uses miniature lenses with micro-motion control to film small things in the wild. It took tremendous patience to sit absolutely still behind the camera to catch the fleeting but epic moments of bee life he eventually recorded. “Absolutely still” is no exaggeration; Dohrn recounts how even blinking could make the camera shake and images lose focus.

The results are stunning. I’ve been involved in making a number of films about bees, worked with some excellent videographers, and have probably viewed every documentary and movie made in the last 40 years with wild and managed bees as their stars, but My Garden reaches a whole new level of visual and storytelling brilliance.

Individual bees move quickly in and out of Dohrn’s visual field without blurring, yet somehow backgrounds and landscapes are sharp and distinct. The camera’s focus is precise, clear enough to see individual hairs on the bees’ bodies, and even single pollen grains dislodged as bees forage on flowers. Motion is often slowed, revealing behaviors too rapid to adequately appreciate with the naked eye. His minuscule cameras come equipped with tiny microphones providing excellent sound pickup, so bee movements are accompanied by audio that enhances our experience as we immerse ourselves in closeups of bee behaviors.

The visuals alone would be well worth viewing, but Dohrn is a consummate storyteller, using the amazing visuals to uncover some fascinating natural history stories about the wild bees we come to know in the film. Of the more than sixty species he finds over a Summer, we get to know yellow-faced (genus Hylaeus), sweat (Halictus), bumble (Bombus), honey (Apis), scissor (Chelostoma), hairy footed flower (Anthophora), nomad (Nomada), mason (Osmia), wool carder (Anthidium) and leaf cutter (Megachile) bees intimately.

Early on, we become acquainted with the hairy footed flower bee, both females and males. The females’ location was more predictable than most bees, because they create what Dohrn calls “perfumed bee highways” as they scent mark their route to find their way to productive flower patches and back home to their nests.

It’s the male hairy footed flower bees that are most remarkable, however. The males live in a world more chemical than visual, with hairy legs that are remarkably perceptive. We see males landing on wasps, flies and other bees, using their legs to taste and identify potential mates, quickly leaving if they’ve landed on something not a female hairy footed. When they do land on a female, Dohrn slows down the encounter so we can see the males sensually stroking the female’s antennae with his front legs. We watch as she visibly calms, presumably recognizing the interloper on her back by scent as a potential mate rather than a predator.

Like Dohrn, we soon became enamored of our male hairy-footed friend, but alas, he is to meet a tragic fate. A green-fanged spider awaits near a potential nesting hole for a female hairy-footed bee. When the male flies over to explore the hole, seeking a potential mate, the spider strikes at lightning speed, and the male hairy-footed flower bee becomes food.

The red-tailed mason bee is another remarkable subject of Dohrn’s camera. She nests in empty snail shells, a behavior that’s well-known but I doubt has ever been filmed with the exquisite detail revealed by Dohrn’s Frankencam. The bee first turns and turns the shell, digging it into the ground and positioning it so the entrance is obscured. She adds leaf pulp and mud, and then spends hours choosing hundreds of blades of dried grass to bring back to the shell, weaving them together to build a strong protective tent that disguises the nest from parasites.

Dohrn’s most intimate portrait is of a leaf cutter bee, Nicky, whom he could identify individually because she had a small nick at the end of one wing. We see Nicky cutting leaves she uses to line three tunnels in which she lays eggs, and out gathering pollen that she packs onto her abdomen for transport back to the nest. There’s drama as well; a crab spider grabs Nicky, but she manages to sting it and escape, which I imagine elicited a collective sigh of relief from the audience when My Garden was viewed in theaters. Like Dohrn, we’ve become fond of Nicky.

Changing our perceptions of fellow humans from general stereotypes to an individual with unique behaviors and history, someone we know as a unique person rather than “the other,” is a classic way to build empathy. Dohrn uses individualization to good advantage as he personalizes bees, building a case for preserving bees without ever having to lecture us about it. He surprises himself by his affection for Nicky, and for another bee, One-tenna, who has half of one antenna missing. Dohrn muses that “bees are not all identical;” by the end of the season his becoming involved with individual bees “changed my view of insects altogether, changed my view of the world altogether.”

Whether it’s caring for individuals, or the remarkable behaviors revealed by Dohrn’s breathtaking videography, he’s undergone a shift by the end of the film. He’s amazed “that so much diversity can exist in such a small space, as spectacular as anything I’ve ever seen before, transporting me to another universe, another dimension of existence.” We in the audience have accompanied Dohrn on his journey of discovery, with greater understanding and wonder for what goes on in a simple patch of flowers.

But will it be enough? Will the legacy of the film be action to save the bees, or will its impact be limited to a historical record of what we lost by not responding effectively to human-caused environmental tragedies?

The statistics are stark for the demise of both managed and wild bees, indeed for all insects. For honey bees, an average of 43% of all U.S. colonies have died each year for the last five years. A 2017 report from the Center for Biological Diversity noted that half of the wild bees in North America and Hawaii are in decline, with one in four wild bee species at risk of extinction. Globally, 40% of wild bee species are rated as threatened, and a 2021 report in the journal One Earth indicated that 25% of known wild bee species globally have not been seen since the 1990s, either having become rare or gone extinct. And the declines are not just for bees; a well-known 2017 German study published in PLOS ONE found that the biomass of all flying insects has declined 75% since 1992.

The causes of bee, and insect, decline are well-known, although the importance of each factor may differ between regions across the globe. Habitat destruction, largely due to agriculture and forestry, pesticide use, diseases (particularly viruses) and climate change are the four most-cited culprits, and there’s general agreement among scientists that these are the leading factors decreasing insect populations. Most also agree on the economic impacts, particularly for diminished bee populations whose diversity and abundance are so important for pollination, with crop losses estimated in the tens of billions of dollars annually.

Can we stabilize bee populations, or even better reverse the decline so that bees will prosper once again? The required actions are obvious but daunting, including a global overhaul of how we produce food and manage forests, transitioning to sustainable and/or organic systems without reducing productivity. And then there’s climate change, an earth-wide problem that is proving resistant to our dependence on fossil fuels and foot-dragging by governments in implementing the drastic actions necessary to reduce the carbon dioxide and other emissions that are causing climate perturbations.

Globally, our way forward may look grim, and perhaps we won’t dig ourselves out of the environmental mess we’re making of the world we depend on. Still, there must be a screw loose somewhere in my psyche, because, in spite of the evidence, I remain optimistic that we can and will do better, and that bees will rebound.

Perhaps a good place to start is to foster home gardens that insert awe into our daily lives, changing lawns into meadows and hedgerows blooming with a profusion of flowers from early Spring through late Fall. Perhaps, as Dohrn did, we could all spend some time each day noticing the minuscule, appreciating the wondrous anatomies and behaviors of the many bees whipping in and out of our vision, reveling in the interdependent relationships between plants and bees that model how we, too, might better understand our reliance on healthy ecosystems.

Backyard by backyard, that’s how to begin the fight to reclaim our planet as a place where wild bees, and we humans, can thrive. Dohrn has done us a great service by offering a glimpse into his own backyard, a space that “just lets some of the wild back in,” tiny in area but immense in what we can learn by dwelling in its glory.

The film can be streamed for free in the U.S. on PBS, is available for rental or purchase at Amazon.com, and for purchase at https://shop.bbc.com/products/my-garden-of-a-thousand-bees-23480.

Mark L. Winston is a Professor Emeritus and Senior Fellow at Simon Fraser University’s Centre for Dialogue. His most recent books have won numerous awards, including a Governor General’s Literary Award for Bee Time: Lessons from the Hive, and an Independent Publisher’s Gold Medal for Listening to the Bees, co-authored with poet Renee Sarojini Saklikar.