Click Here if you listened. We’re trying to gauge interest so only one question is required; however, there is a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

Dealing with Beekeeper Guilt

Dealing with Beekeeper Guilt

Caused by Reduced Beekeeping Practices

By: James E. Tew

This is not a negative article

While it may sound like it is, this is not a negative article; however, it is a realistic piece. Many articles in Bee Culture Magazine present beekeeping management information that help the evolving beekeeper manage their colonies perfectly. Yes, problems and challenges will always arise, but when they do, some of the published articles explain what procedures would be required to get colonies back to high standards. That’s always the goal – perfect colonies in a perfect yard. It’s a lofty aim.

A “beekeeper” is not a standard designation

The ability and energy of individual beekeepers are all over the page. Few things about us, as a group, are standardized. But to many of the population of this country, who do not keep bees and know nearly nothing about them, being a “beekeeper” is a unique designation. When viewed by this large group, all beekeepers are seen as being the same. Cookie-cutter as it were.

Yet, within our group, there are beekeepers who are on the job night and day, and their colonies normally show the positive results of their energy allocation. But there are also beekeepers who are not able, or inclined, to contribute large amounts of their life’s resources to managing their bees. The colonies of this group may, or may not, show the effects of their laissez-faire philosophy of bee colony management. It’s difficult not be judgmental, isn’t it? It would seem that every beekeeper should strive for perfection beekeeping. I sense that is never going to happen.

It’s not just beekeeping

For instance, as you drive down a suburban street, have a look at the variation of the home maintenance and landscape each house has. Some homes are perfectly manicured while others have not been given the same level of attention. Is one homeowner more deserving of respect than another?

It depends, doesn’t it? Are city ordinances being violated? Is clutter excessive? If homeowner basics are being met, do we not expect some homes to be better maintained than others? Common reasons for this variation are simply innumerable. It’s just the way of things. The same is true with beekeepers.

Figure 1. This dog is a perfect example of a pet.

Bees are not pets

Bees are not actually pets, but they have commonality with pets and other domestic livestock. Obviously, pets and livestock must be nurtured and maintained. In fact, they are protected in many legal and moral ways.

Due to challenges like varroa predation, honey bees are similar to pets and domestic animals. Without human assistance, managed honey bees do not normally thrive. Colony decline and death are the frequent outcomes. So, beekeepers, you need to take care of your bees. But the devil is in the details. Exactly how much care is necessary?

It really gets tricky at this point. Bees are wild animals and, as such, should be able to fend for themselves without human assistance. Yes, that’s true, but feral honey bees conduct their natural lives differently in several notable ways. In the wild, colonies do not normally grow nearly as large as managed colonies and they do not produce as much surplus honey. Plus, they swarm more often. A wild colony provides incidental pollination rather than directed pollination. For instance, you can’t move a feral colony to a commercial apple orchard. And finally – and importantly – they frequently die during the Winter.

At this point, enter the beekeeper and their artificial domiciles. For the bees in managed hives, many things change. Beekeeper care is required to help the colony thrive under these artificial conditions. But again, exactly how much care is necessary?

Figure 2. This animal is not a pet, but it is treated as one.

Everything changes

In life’s big picture, everything changes. As we age, many things about our lives change, too. When change comes our way, we adapt. We reallocate. We improvise. We refurbish ourselves. As life’s “things” morph, we do whatever it takes to embrace and incorporate the changes and push our lives forward. We really have no other choice.

Beekeepers and their relationship with their bees are no different. A dedicated beekeeper may not always be able to commit to all the demands that perfection beekeeping requires. Should they quit the craft? No, but they will need to adapt and reallocate the resources they still have.

Sloppy beekeeping

I am not condoning sloppy beekeeping. I feel that I need to write that again – in this article, I am not condoning sloppy beekeeping. But sometimes, try as we might, things change in our lives and our energy and commitment to our bees can seem to approach something that resembles “sloppy” beekeeping.

Job changes, health changes, monetary changes, marital changes or societal changes are examples that can cause a staid beekeeper to have to consider a restructured management level compared to the level they were previously maintaining. Sometimes these changes are temporary while in other instances, they are permanent.

Blended beekeeping

Is what I am naming “sloppy beekeeping” simply “blended beekeeping?” For instance, let’s say that things have changed and we are forced to back down our commitment and contribution to the bees’ way of hive life. If the bees can’t make up the difference, they will most likely die. In my view, this mix of feral schemes with managed schemes could be named blended beekeeping.

Things changed

Okay, it happened. Big changes have occurred. Let’s say the beekeeper retired and had experienced some health declines, but they still are devoted to beekeeping. What are some ways they can adapt and alter their beekeeping protocols?

Be a hobby beekeeper

Bluntly, if big changes are coming your way and you want to stay in beekeeping, you should most likely consider being a hobby beekeeper. Proficient sideline and commercial beekeepers are already being as cost and labor conscious as possible. They live in a different management world and are answering to different management mandates. It’s the hobby beekeeper who can reduce or alter their standards without serious retribution.

The apiary

There are no lawnmowers, string trimmers, and herbicides in the bees’ natural world. That’s all on us. In perfection beekeeping, the grass and weeds are kept mowed and trimmed. Yes, colonies with artificially low entrances will probably appreciate this work, but will uncut grass be the premier reason that a colony dies during the Winter? Probably not. Will the apiary look scruffy and not be photogenic? Definitely.

But if the weeds and brush are allowed to truly run rampant, the beekeeper will nearly be unable to walk to the colonies – much less remove honey or perform colony manipulations. Maybe the recommendation should be to “cut back” but don’t “cut out” weed maintenance.

Figure 3. Perfectly functional, but minimally maintained hive equipment.

The hive equipment

Even in reduced labor and energy situations, hive equipment should be assembled correctly. When filled with bees or honey, equipment will surely be stressed as it is moved and manipulated. If you are having strength and health issues, heavy hive equipment will sometimes be handled roughly – even dropped.

Either don’t paint or only paint once and forget it. (That comment is a pain for me to write. My Dad had a paint supply business. I spent my early life dealing with all things paint. Now, I am suggesting that you cut out painting.) Yes, thorough paint applications will help wooden equipment 1Plastic hive equipment, made of expanded plastic foam, should be painted. Otherwise, it’s useful life is shortened.) last a bit longer and it will certainly look better. But really? How much longer will it actually last, or is looking good the primary goal? Maybe the recommendation should be to assemble the equipment soundly but, if necessary, skimp on the protective coatings. Distasteful, isn’t it?

Colony manipulations

Colony opening events can be significantly reduced if labor and energy are to be lessened. After a new beekeeper has acquired the necessary basic skills, whimsically opening a colony is not often necessary. Much can be determined by simply being aware of the season of the year and reading entrance detritus evidence – but make no mistake here. Reducing colony manipulations will limit the beekeeper’s ability to stay intimately aware of the colony’s condition. But the question re-arises at this point – how many colony manipulations are necessary to meet the minimal? That’s an unanswered question. How much are you willing to give up?

Lost swarms

All beekeepers, at all levels, will lose the occasional swarm. Alternatively, sometimes all beekeepers will acquire a swarm that moves into empty equipment or they will acquire a free swarm that they hive. Either way, swarms happen. They come and they go. But reduced colony manipulations will require the beekeeper to be more tolerant of lost swarms.

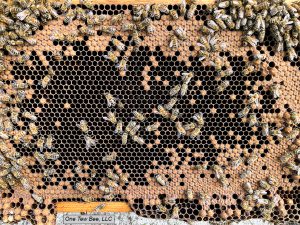

Figure 4. A good brood frame. When I view this photo in my photo processor, there are visible eggs in the center of comb. I do not need to find the actual queen.

Queen productivity

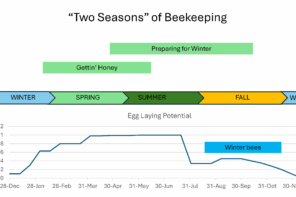

The more committed a beekeeper is to their colonies’ management, in general, the more anxious they are about the queen stock heading their colonies. Again, being aware of the season, a beekeeper, who has elected to implement “blended beekeeping” concepts should know what a suitable brood pattern would look like during that season. In this way, the investigative beekeeper evaluates the seasonal brood and brood pattern rather than the actual queen. In many instances, no effort, at all, is made to see the queen. Just seeing eggs or seeing the queen’s brood pattern is normally enough for a quick inspection.

I don’t sense a strong argument for the minimalist beekeeper heavily investing in high quality replacement queens. Escaped swarms will most likely be an issue, and they will take costly replacement queens with them. If one is not making splits or is not suppressing swarming and has only a casual interest in surplus honey production, naturally produced queens will meet most needs. For all beekeepers, marked queens are a good idea.

Yes, reducing queen management will greatly reduce time and economic demands. But at the same time, that management pathway will reduce overall colony productivity. Can you – or should you – live with that fact?

Mite management

Like swarm suppression or queen management, Varroa mite control requires time, labor and money. This is a serious aspect of honey bee management. If the beekeeper does not implement a conscientious mite control program, most likely that colony will die and will produce mites that will invade surrounding colonies not yet dead.

Managing mites is one of those instances when the colony should be opened for treatment. There are few ways to cut corners on this issue. If the beekeeper does not implement mite repression programs, then next Spring, to replace dead outs, the beekeeper will be required to purchase bees (packages or splits) from beekeepers who did implement such programs. I can’t see that much money or labor was saved by taking this tact.

Honey processing

Surplus honey removal and processing is a huge labor and energy drain. In past articles, in this magazine, I have written that honey processing is not beekeeping. Indeed, I know a few specialists who only process honey and have few colonies of their own. They contract-process honey for other beekeepers.

In the bright light of reality, capped honey can be taken off at nearly any time of the year – even in the dead of Winter. I don’t know why you would do that since it only makes for a miserably, cold job, but neither do I know your exact situation.

Before extracting, frigid honey would need to be allowed to warm up, but not held too long. Without bees to protect it, that warming interlude gives an opportunity for Small Hive Beetles and Wax Moths to begin damaging the combs. Other than producing comb honey, I cannot think of a way to easily short-circuit the cumbersome process of setting up an extractor and dealing with the folderol that comes from honey processing. I suppose that contract processing would be an alternative.

Dramatically, one could simply leave the surplus honey on the wintering colony. Even for the reduced labor beekeeper, in cold climates, I would suggest wintering the colony in one or two deeps and moving the capped honey supers above the inner cover. In this way, theoretically, the colony could better manage its wintering environment. Honey, held like this, could be used the next Spring as supplemental food for initiating replacement colonies or for giving food to other needy colonies in the apiary.

My point

My point in this piece is there are beekeepers who, for whatever reason, cannot or do not commit to maximally managing their colonies. Representatives from this group are rarely asked to give presentations on their management procedures. There are no articles published in bee magazines for this group, and these beekeepers rarely speak out at meetings. They quietly hang on.

We all have our reasons and procedures that allow us to continue to co-exist with our bees. As I wrote before, “The ability and energy of individual beekeepers are all over the page.” There is no standard beekeeper.

Thank you for reading this piece.

Dr. James E. Tew

Emeritus Faculty, Entomology

The Ohio State Universitytewbee2@gmail.com

Co-Host, Honey Bee Obscura Podcast

www.honeybeeobscura.com