Annual U.S. Colony Losses Hit Record High Over Winter of 2024-2025

Ross Conrad

These words are being written at the end of February, but by the time you read this, chances are you have already come across alarming headlines of recent massive U.S. honey bee losses. Results from a Project Apis m (PAm) survey found that since June 2024, over 1 million colonies – an estimated 62% of commercially managed hives – have died. The losses of the last nine months eclipse all of last year’s losses that an Auburn University, Apiary Inspectors of America (AIA) and Oregon State University survey found to be just over 55%. This year’s Winter die off ranks among the highest level of honey bee loss since efforts to monitor annual hive deaths first began with the advent of CCD in 2007.

According to Danielle Downey, Executive Director of PAm, “…this year there were a lot of beekeepers that were surprised by the number of dead and dwindling colonies. And as they mounted the beekeepers started to call researchers and say ‘We need some help. We don’t now what’s going on. Something is definitely not right. Something happened and we’re hoping that you can help us and get some answers.’ So as that was happening, PAm was asked to put out a survey to determine if these things were widespread or regional; to see what the beekeepers were seeing and how bad it was; if there was anything obvious, a common factor; and what we would need to do to provide resources to help.”

Preliminary survey results

The breakdown of the over 700 beekeepers that have participated in the PAm survey so far, found that backyard beekeepers (1-49 hives) lost an average of 50%; sideliners (50-500 hives) lost an average of 54%; and commercial operations (over 500 hives) lost and average of 62%.

These results echoed last year’s colony loss survey that for the first time found that commercial beekeepers lost a higher percentage of their colonies than backyard beekeepers. Historically, part-time backyard beekeepers that typically have less experience, knowledge and resources compared to commercial operations that rely on their bees for their livelihoods, lose a higher percentage of bees annually. The conservative estimate of a 62% average loss among commercial operations is also above the estimated average number of hives lost during the height of CCD in 2006-2008.

Research community and industry mobilization

The alarming number of colony losses has galvanized the industry to uncover the cause. A team of over a dozen highly skilled and experienced scientists has mobilized to analyze the survey data and follow up with the testing of bees, wax and pollen samples. Says Downey, “…a lot of expertise from the USDA labs and from universities is looking at the regional data and geography, the mite treatments, the disease trends, nutrition and landscape impacts, economic damage estimates and also pesticide concerns.”

Additional support is being offered from all across the beekeeping industry from organizations such as the One Hive Foundation, the Honey Bee Health Coalition (HBHC), the American Beekeeping Federation (ABF), the American Honey Producers Association (AHPA), extension offices, the Apiary Inspectors or America (AIA), and even beekeeping clubs.

Scientists from the USDA bee research laboratory in Beltsville, Maryland responded swiftly to the crisis by traveling to California as colonies were being moved to pollinate almond orchards and collected samples for study. Samples were taken from dead hives as well as weak and dwindling colonies. Samples were also obtained from healthy colonies that will act as controls and can be used to compare results between the weak and dwindling hives and the strong hives.

Wide-ranging in-depth analysis underway

Downey went on to explain the comprehensive nature of the investigation to find the source of the problem. “We don’t have all the answers yet, but we’re feeling great about the team that we have. In addition to the survey, the samples that were collected in California will be the subject of an ongoing study and among the things that will be probed in those samples are pathogens, and this is known honey bee pathogens using molecular methods and previously unknown pathogens in bees that would be detected with metagenomic analysis.

“I’ve been questioned if this could be bird flu for example. If bird flu is in there, although there is no precedent for it being in there, the metagenomic analysis would pick that up.

“Of course, pesticides are a concern for beekeepers and so the pollen that was collected out of those colonies will be screened for pesticide residues and we’ll also be looking at pollen diversity. The pollen that they have in their bee bread is a snapshot of the landscape and nutritional forage that was available to those bees. So that’s another layer they’ll be looking at in these bee bread samples to see what the bees were foraging on.

“Also the micro-biome and host pathogen interactions will be studied in these samples. And we know there is a problem with Amitraz resistance and there’s a lot of concern that maybe this is the explanation, and these samples will be analyzed for the genetics of Amitraz resistance as well…”

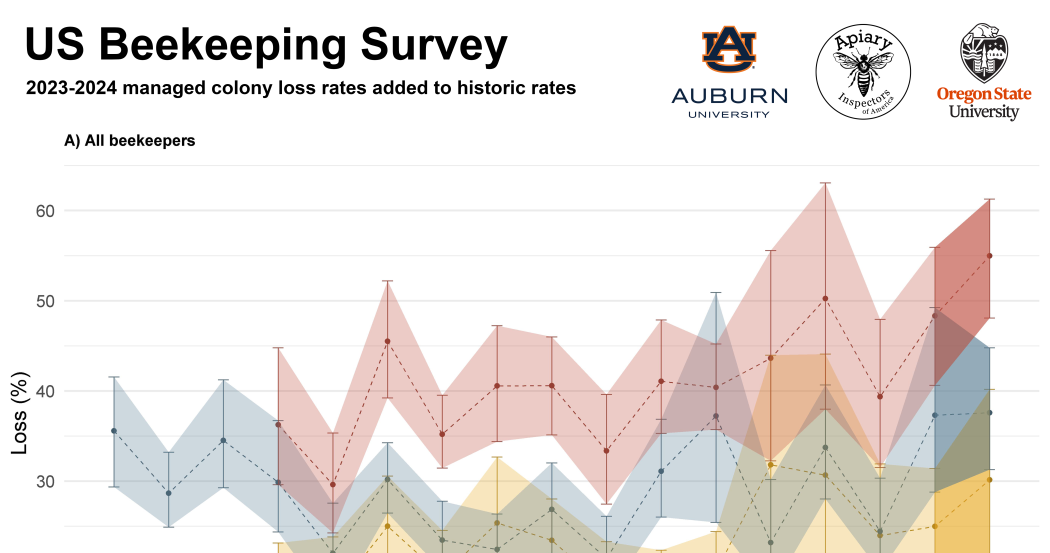

“Colony loss data gleaned from surveys of beekeepers and broken down by time of year and size of beekeeping operation. In general colony losses have been trending higher across all operations and times of year over the last decade and a half.”

No smoking gun so far

At the time of this writing the survey data available does not appear to implicate beekeeper management decisions as the cause of the extensive losses. For example, the data indicates slightly higher losses among beekeepers that wintered their bees outside compared to those that wintered inside a climate-controlled environment. While wintering in buildings appears to have some advantage, the survey does not appear to reveal the kind of difference that one would expect to see if outdoor wintering was the primary cause of the bee losses.

The survey inquired about beekeepers that replaced queens and those that didn’t to see if there was an obvious correlation there. While commercial operations that replaced over 50% of their queens experienced a slightly higher loss rate, it was not a large enough difference to explain the heavy losses across the board.

While there were slight differences in survival among beekeepers that fed and those that didn’t, there was also no clear pattern among beekeepers that fed supplementary sugar and protein, sugar only, protein only or didn’t feed at all.

Mites are constantly being blamed for high colony losses and the survey data reveals a wide diversity in how the nation’s beekeepers approach the varroa issue. Some beekeepers monitor for mites regularly and some not at all. Of those that monitor, colonies went into Winter with mite loads that ranged between zero and about 5 mites per 100 bees. Initial reviews of the data however do not appear to implicate mites as the cause of the extraordinary losses beekeepers are experiencing.

Challenging work environment

What makes the current effort to uncover the cause of this Winter’s dramatic colony losses even more remarkable is that it is going on during an incredibly difficult time for USDA labs and universities around the United States right now. Many are short staffed and have been prevented from hiring additional help by a Presidential executive order. Some labs have lost grant funding and had to let staff go. At the same time many have lost additional staff due to the exuberance with which the government shakeup that is purported to be about cutting federal spending is firing civil servants and employees across all areas of government, sparing only law enforcement officers and agencies working on immigration and border protection.

While beekeepers who are experiencing catastrophic losses are being encouraged to apply for relief through the Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honeybees, and Farm Raised Fish Program (ELAP), things are changing so quickly with federal programs between the budget cutbacks, grant cancellations, and staffing reductions that it is hard to known how well ELAP applications are going.

More information is better

We all have busy lives but any time a beekeeping survey is released, we all would do well to take the time to fill it out. The greater the number of beekeepers that participate in such surveys, the more complete the data available to researchers will be and the better they can help our industry find the answers we need.

A silver lining

If there is any silver lining to be found in this situation, it is that like the super organisms we all know and love, the beekeeping industry finally appears to be putting aside its petty differences and coming together to speak with one voice and act with a unified purpose. Meanwhile beekeepers will continue to do what they have always done which is to pick themselves up and dust themselves off the best they can while they use their surviving colonies (if they have any) to rebuild their apiaries and operations.

While there are lots of theories, we will have to be patient while researchers do the painstaking work of trying to figure out what exactly is afflicting our nation’s beloved pollinators. Until we do, as Director Downey says, “…we don’t really know what’s going on and a catastrophic loss could happen again.”

Editor’s Note: PAm Executive Director Downey’s quotes were lightly edited for clarity and length.