By: Vaughn Bryant, Texas A&M

There is very little truth in honey labeling.

“Houston, we have a problem!” Those were words that echoed around the world on April 13, 1970, when Jack Swigert, pilot of Apollo 13 reported an explosion on his spacecraft that caused the loss of almost all of their reserve power and oxygen. Fortunately, the story had a happy ending because the astronauts were able to solve their problems as the World listened breathlessly to every hourly report of progress.

“Houston, we have a problem!” Those were words that echoed around the world on April 13, 1970, when Jack Swigert, pilot of Apollo 13 reported an explosion on his spacecraft that caused the loss of almost all of their reserve power and oxygen. Fortunately, the story had a happy ending because the astronauts were able to solve their problems as the World listened breathlessly to every hourly report of progress.

“Honey, we have a problem!” That statement may not be as earth-shaking but for us in the United States we do have some serious problems with the purchase and sale of honey. I know this because I have been analyzing honey samples for more than 40 years and I have been working on this problem for almost as long. The major problem is the identification and labeling of honey sold in North America. The federal laws that govern labeling honey are minimal and pertain only to the definition of “raw and natural” honey as being a product to which you cannot add anything else such as additional water or other ingredients including high fructose corn or rice syrup. The laws do allow a person to “remove” unwanted materials such as insect parts and other debris, including all of the pollen in honey. It is this last point that has created the biggest problem in terms of identifying the geographical origin and floral sources of a honey sample.

The January 16, 2017, issue of TIME MAGAZINE featured a story on health called “The growing fight against food fraud,” which focused on the misidentification of foods on US grocery shelves. Their testing showed that for some products what is stated on the label is not what is actually in the box or jar! One of the food items they discussed was honey. They noted their testing found Italian olive oil that was neither from Italy nor from olives, cumin spices consisting of ground-peanut powder, and “natural” honey that was laced with antibiotics. But this is just the tip of the iceberg! So why doesn’t the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) enforce truth in labeling? For the most part they argue that they are overworked and underfunded and that their primary concerns are investigating serious, life-threating outbreaks of bacteria and viruses that endanger people’s lives. Therefore, checking the accuracy of food labels is not one of their high priorities. After all, an incorrectly labeled honey sample probably isn’t going to kill you!

Incorrect labeling on a jar of honey might not kill you but should you pay a premium price for sourwood or buckwheat honey, tupelo or orange blossom honey, or even Manuka honey when what is in the jar is cheap junk and not the premium honey you think you are buying? I know about this problem because we have done a number of investigations to discover if labels on jars of honey match the contents.

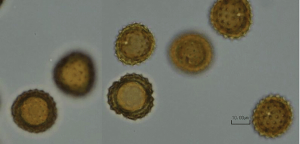

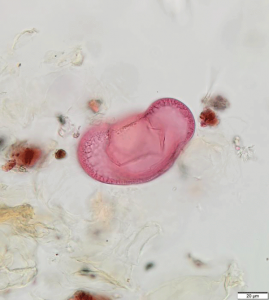

In 2011, Andrew Schneider (AKA, the Food Watchdog) and I teamed up to see just how accurate honey labeling might be in grocery stores throughout the U.S. We purchased more than 60 jars of honey on store shelves in 10 different states and Washington, DC. We then conducted pollen testing of each sample to determine the geographical origin and floral contents. We wanted to see if the actual contents matched what was written on the labels. What we discovered is that 76% of all the honey samples purchased in grocery stores had all the pollen removed from the honey. All of the varieties of honey sold at Walgreens, Rite-Aid, and CVS pharmacies contained no pollen. All of the small packets labeled as “honey” that were sold or used by Smucker, McDonald’s, and Kentucky Fried Chicken contained no pollen. Seventy-one percent of the honey samples we purchased that claimed they were organic and from Brazil, actually did match the labels; at least we could prove they were from Brazil but we could not prove they were organic. In other tests we purchased “local honey” from roadside stands and in local grocery stores and found that the majority of those samples were not “local” but actually came from distant locations, often from some place in the Great Plains of the Central United States. We also purchased honey at health food stores and from whole food stores that champion their organic and wholesome foods only to find that they also were selling mislabeled honey, which often surprised them.

In one food store in Texas I purchased honey from a large five-gallon container labeled, “pure Texas Huisache honey.” That is a premium honey that comes from a native Texas bush called Acacia farnesiana. When I analyzed the sample I discovered that it was not Huisache honey; instead, it was a blend of honey from several different locations, one of which was Texas but there was no trace of Huisache in the sample. When the store manager was confronted with that information he replied that he didn’t realize the label was wrong because the person who sold him the honey said it was Huisache. When I suggested he might want to change the label he said he didn’t think so because, “after all, that is what his customers wanted: Huisache honey!” He added that probably most of those buying the honey didn’t care what it was anyway.

So, do consumers really care what they buy? Do they mind paying top dollar for mislabeled products that enable the sellers to reap huge profits by selling cheap alternatives instead? Unfortunately, many people who enjoy honey don’t seem to care what they buy so long as it is cheap. They will buy the cheapest honey product regardless of what it says on the label. However, there are others who are concerned. Those customers expect to get what they pay for. If they buy sourwood or some other premium honey and pay a premium price, they expect the honey to match the label.

Unfortunately, we can’t turn to the Federal Government for any type of help with this problem. According to federal laws, requested by the USDA and then passed by Congress, the United States has the following rules and definitions for honey produced locally or imported, and sold in the United States. This law is part of the FDA’s United States Standards for Grades of Extracted Honey that went into effect on May 23, 1985. One part of that law states: “Filtered honey is honey of any type defined in these standards that has been filtered to the extent that all or most of the fine particles, pollen grains, air bubbles, or other materials normally found in suspension, have been removed.” Therefore, it appears that the FDA does not have any problem with allowing honey to be highly filtered to remove all particles, including pollen grains.

Unfortunately, we can’t turn to the Federal Government for any type of help with this problem. According to federal laws, requested by the USDA and then passed by Congress, the United States has the following rules and definitions for honey produced locally or imported, and sold in the United States. This law is part of the FDA’s United States Standards for Grades of Extracted Honey that went into effect on May 23, 1985. One part of that law states: “Filtered honey is honey of any type defined in these standards that has been filtered to the extent that all or most of the fine particles, pollen grains, air bubbles, or other materials normally found in suspension, have been removed.” Therefore, it appears that the FDA does not have any problem with allowing honey to be highly filtered to remove all particles, including pollen grains.

Although legal, removing all of the pollen does have consequences. For example, there is no way to prevent commercial honey companies from buying, producing, or selling highly filtered honey where all the pollen has been removed. Unfortunately, by removing all the pollen some of the food value of the honey and the taste is altered from the original, pure, raw honey that is taken from the hive. In addition, this law makes it possible for any type of illegal honey to become part of “legal” honey sold commercially in the United States. For example studies show that in 2014, an estimated 91,000,000+ pounds of illegal honey was imported and then sold in the United States with the vast majority of it going undetected because it contained no pollen that could be used to confirm it was illegal.

Once all pollen traces are removed from honey produced in other countries, some of which carry high tariffs when imported into the U.S., and honey that has been illegally transshipped to other countries and then exported to the United States cannot be identified through traditional studies. Those illegal honey samples can sometimes be identified as to their actual floral and geographical sources though the examination of DNA, isotopes, or the protein contents found in honey. However, those procedures cannot be tested on honey produced in many regions of the world because we lack the needed reference databases to use for standard comparisons. In addition those techniques are time-consuming, require special equipment and trained personnel, and they are expensive to conduct.

Once all pollen traces are removed from honey produced in other countries, some of which carry high tariffs when imported into the U.S., and honey that has been illegally transshipped to other countries and then exported to the United States cannot be identified through traditional studies. Those illegal honey samples can sometimes be identified as to their actual floral and geographical sources though the examination of DNA, isotopes, or the protein contents found in honey. However, those procedures cannot be tested on honey produced in many regions of the world because we lack the needed reference databases to use for standard comparisons. In addition those techniques are time-consuming, require special equipment and trained personnel, and they are expensive to conduct.

If the federal government isn’t going to police truth in labeling for honey sold in the U.S., then what can any other state legislature or agency do; unfortunately, not much. California, Wisconsin, and Florida all passed state laws that prohibit the removal of pollen from honey and also imposed truth in labeling laws for honey. However, none of those states could enforce their laws because the Federal Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (NLEA) states that no State or any political subdivision of a State may directly or indirectly establish under any authority any requirement for the labeling of food that is not identical to the requirement of such section by the NLEA. In other words, since the NLEA enforces the guidelines for foods that are established by the FDA, and since the FDA does not require truth in labeling for honey, then no State or agency in the US can require that honey be labeled accurately. California legislators, who were upset by the rulings against their truth in labeling laws for honey sold in California, tried another tactic. The legislature then passed a law saying that any honey, which has had all of its pollen removed, must state that on the label of the jar. Unfortunately, California lost that case as well because companies, such as Sioux Honey pointed out successfully that there were no federal laws that would require such action.

After these court defeats the North Carolina Beekeepers decided to try a new approach, which could not be enforced by legal authorities, but could be used to convince consumers what honey products could be trusted to be authentic. North Carolina honey producers pride themselves on producing excellent sourwood honey, which will command a premium market price. Because of this, the NC beekeepers began to find that a number of suspicious honey samples were appearing throughout the state and were being sold as sourwood, when in fact many doubted they were authentic. The solution was to agree among themselves that they would only sell authentic sourwood honey and also agreed that their sourwood samples would be tested to prove they were indeed sourwood. Authentic sourwood honey that had been tested could state that on the label with the hope that consumers would learn to look for the seal before purchasing sourwood honey. Beekeepers also purchased suspicious samples that were being sold and had them tested. If proven not to be sourwood then those selling the non-sourwood honey were asked to remove it for sale. How successful this program will become and whether other beekeeping organizations might try similar techniques remains to be seen. This type of testing can also be used to identify true “local honey” from non-authentic honey claiming to be locally produced.

There are others who are also trying to change the way honey is being labeled inaccurately. Lawyers in a Northeastern law firm have been engaged by conscientious groups who are trying a new approach to ensure truth in labeling for honey products. The law firm has selected several dozen commercial honey samples, that are produced by well-known companies, that claim their labels accurately reflect the contents in their jars of honey. This law firm then has the honey samples tested to determine the country of origin and the nectar contents in order to check the statements on the product’s labels. When the contents of the honey products do not match what is written on the label then those companies are sent a copy of the test results and asked to amend what is written on the labels of their honey products. Whether or not this will change the way some companies label their honey products remains to be seen, but the effort is certainly admirable.

We have identified the problem and recognize that there are no current legal methods to ensure truth in labeling for honey products sold in the United States. There is no penalty for those unscrupulous individuals or companies who seek to earn high profits by selling products labeled as premium types of honey when in fact the contents are common canola or clover honey. Federal laws prohibit the adding of anything to honey that is labeled as being honey, but those same federal laws permit the removal of all sorts of particles including all of the pollen.

We need to petition our senators and legislators asking them to pass new laws regarding truth in labeling for many food products, including honey. Unfortunately, to date those types of attempts by individuals and even attempts by the American Beekeeping Federation have fallen on deaf ears. I have often said that the unfortunate reality is that the FDA will probably do nothing about truth in labeling until some type of tainted honey causes the death of individual consumers.

Vaughn Bryant is Professor and Director of the Palynology Lab at Texas A&M, College Station, Texas. He is a frequent contributor to these pages.