Ettamarie Peterson

Up to a century and a half ago, overland shipment of bees to California was considered impossible – travel through the Great Basin and deserts of the Southwest was too arduous. A well-known botanist Christopher A. Shelton first breached that geographical barrier by bringing bees across the Isthmus of Panama on the backs of donkeys because the railroad had not been completed from Aspinwall, Panama to the West Coast. He then put them on a North-bound ship called The Isthmus to San Francisco. The Sacramento Daily Union published an article March 18, 1853 commenting on his saying he also brought with him a lot of gold and silver fish, and a collection of seeds of different kinds.” Shelton managed to get one of the colonies to the Robert F. Stockton Ranch, just north of San Jose, California, but only one colony survived. This colony had multiplied to three good ones by the end of that summer. Unfortunately, poor Mr. Shelton was killed in a horrible steamer disaster near San Francisco just a month after he put the bees on the ranch in San Jose. Two colonies of these German black bees were sold at an auction to settle his estate. One was sold for $105 and another for $110. Shelton’s bees’ arrival has been commemorated by a plaque at the Santa Jose Mineta International Airport outside Terminal C by the E Clampus Vitus organization (a group started during the Gold Rush to make fun of other more serious groups). The plaque states, “First Honey bees in California. Here, on the 1,939-acre Rancho Potero de Santa Clara, Christopher A. Shelton in early March 1853 introduced the honey bee to California. In Aspinwall, Panama, Shelton purchased 12 beehives from a New Yorker and transported them by rail, pack mule, and steamship to San Francisco. Only enough bees survived to fill one hive, but these quickly propagated, laying the foundation for California’s modern beekeeping industry. California Registered Historical Landmark No. 945.”

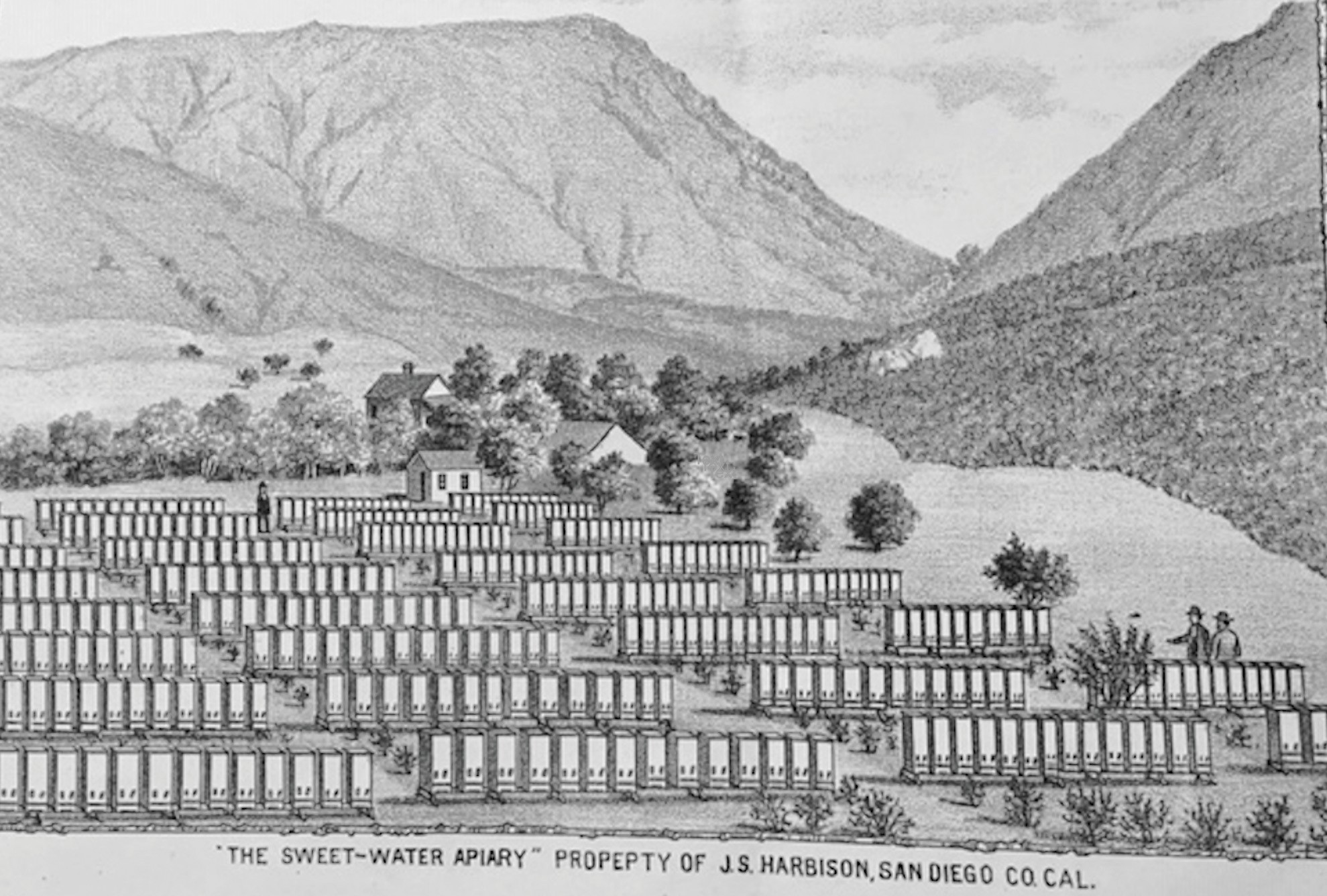

Other shipments followed, imported by John Harbison and others during the mid-1850s. Harbison had abandoned gold mining to start the first nursery of fruit and ornamental trees in the Sacramento Valley but soon turned to his prior skills of beekeeping on a large scale. He designed the best shipping boxes to get the bees to California in good shape from his home state of Pennsylvania. His first shipment was made in 1857 and arrived in San Francisco in November. They were then put on a river boat to the City of Sacramento. The journey was made easier by the completion of the Aspinwall Railroad’s 47 miles of train track at the end of January of 1855. Harbison’s brother was still in Pennsylvania and followed his instructions to prepare the hives for the journey. He also knew what time of the year was best to start the westward journey. He was not the only one to transport bees, but his methods proved to be the most successful. He became known as the “Bee King of California.” (San Diego County has named a canyon after him.) He invented the “California Bee Hive” patented January 4, 1859 and published The Beekeeper’s Directory or the Theory and Practice of Bee Culture, in all its departments, The Result of Eighteen Years Personal Study of Their Habits and Instincts in 1861 in San Francisco by H.H. Bancroft and Company.

Honey bees were dispersed throughout California. By 1860 a thousand colonies were already present in San Jose. His hive was designed to make comb honey in nice, easy-to-ship comb honey boxes. That was a very smart choice as he became at one time the largest producer of honey in the world selling his honey across the nation and across the Atlantic. The invention of the honey extractor made the Langstroth hive the more favorable hive a few years later.

The Transactions of California State Agricultural Society for the year 1859 stated:

“We would next report in reference to Mr. Harbison’s Hive. This Hive is a California invention, and combines the great requisites necessary to the successful raising of Bees, namely: having perfect control of the combs, by means of the sectional frame, which is so adjusted that it is firmly held at proper fixed distances, and can be removed without the least jar; it also has the inclined bottom, and there are no useless parts to form a harbor for worms, or accumulation of filth, to facilitate their increase.

While the Hive is constructed on natural principles, giving proper depth of comb, enabling the Bees to concentrate the animal heat to the best advantage, thereby insuring a large increase of Bees, and consequently of honey, the ventilation is on a new principle, so arranged as to admit air without light, when required, and be reduced or increased easily.

The surplus honey-box is made in sections, so that while the largest yield of honey is obtained, it is yet separated in small parcels, in a beautiful shape for the table.”

In 1860 people were definitely getting the bee fever. One beekeeper wrote an article to the Farmer that was quoted in the Sacramento Daily Union in December 1860 declaring: “Three years ago I began with five swarms of bees, for which I paid $500, and was my entire capital, except a team worth $400. I used the common chamber hive the first season, and my increase of stocks was less than three to one. At the beginning of the second season I introduced and practiced, in an imperfect manner, the Langstroth system, and at the close of that season I sold 103 stocks for $10,300, having fifty stocks left. During the third, which is the present season, I have practiced the same system in a more perfect manner, and the result of the fifty stocks has been about 600, which contain full forty pounds of honey each, or 24,000 pounds in the aggregate. I am selling them now at $50 a stock, and I believe that they will be worth twice that money to those who buy them. For the last two seasons I have employed one assistant, who has made most of the hives. My hives cost me less than two dollars each. From these facts and figures, it will be seen that the five swarms, with three years’ labor have paid me a considerable over $30,000.”

This was the same time the Italian bees were starting to arrive from New York. The California Farmer and Journal of Useful Sciences announced the Italian bees’ California arrival in their December 14, 1860 edition. The first Italian bees to arrive, the article said, came from an apiary in Northern Italy. These Italian bees were highly praised, and the author of the article predicted their success. The last sentences of the article said, “Much expense has been incurred in introducing these Italian bees here. We are informed the Italian queens will be propagated as fast as possible during the coming Spring at Sacramento and Stockton and furnished to those wishing them on very reasonable terms.” At this time there was some foul brood showing up in the German Black bees and the thought among beekeepers was that the Italian bees would be better survivors. The beekeeper A. J. Biglow that brought the Italian bees said he sold some to Harbison.

Twelve years later Harbison took 308 hives of Italian bees from his apiary just south of Sacramento to one of his five apiaries he had established in San Diego County beginning in 1869 with beehives he moved at that time by ship. The high mountains of 2,000 feet to 3,000 feet altitude near San Diego had plentiful rain which produced excellent bee forage for a long period of time.

In 1871 Harbison shipped a railroad car load of Italian hives to work in Utah. That was so successful that the following year he had an order for another car load he sent around the first of March. In 1873 Harbison shipped the first car loads of his comb honey to Chicago. Later he would ship his comb honey further East.

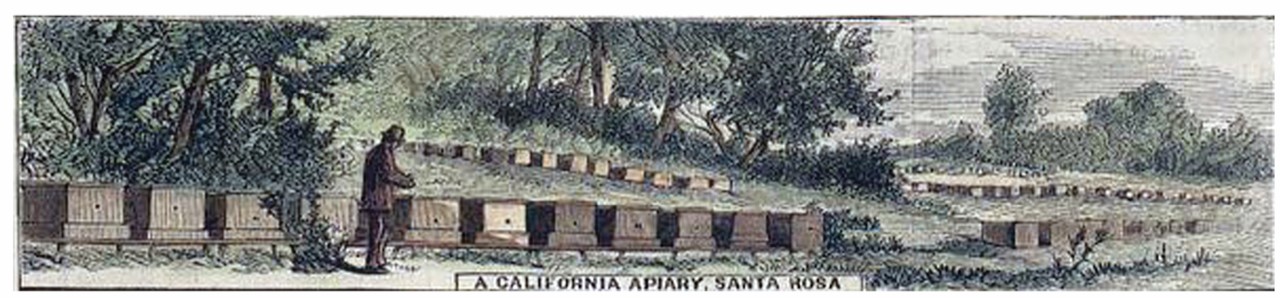

In 1875, the Press Democrat published a story about two young lady school teachers from Oakland, California that went down to Los Angeles in 1872 and formed a co-partnership in bee farming. By the time of the article, they had used their scant teacher saving to get possession of bee pasture, kept on teaching and extended their business. They had 2000 pounds of white sage honey for the market and another thousand pounds coming. The authors of the article didn’t think beekeeping would be as profitable in Sonoma County as in Los Angeles so were encouraging the ladies here to make a profit in raising poultry and eggs.

By 1876 there was an organization of beekeepers that met in Los Angeles. At their June 17th meeting a paper was read ridiculing the notion of many persons about the profits to be realized in the bee business with little or no labor and expense. Another beekeeper spoke of hives melting down and the best way of preventing it. Harbison told the society the best way to obtain adequate returns for their products. He said, “The present prospect for the sale of honey was gloomy, because at this time of the year but little honey is consumed.” He advised beekeepers to keep their honey until September, October and November when honey would be in better demand for actual consumption. In regard to the business in San Diego County he said there would be little sage honey this year. The principal harvest would be from sumac and buckwheat greasewood.

In July of 1876 it was proposed to organize a State beekeepers’ association. The person proposing it said such organizations exist in most of the States. The California State Beekeepers’ Association came into existence in 1889.

In early 1878 a beekeepers’ meeting was held in Southern California. At that meeting a resolution written and adopted stating, “Resolved, That we urge upon beekeepers throughout the State of California to petition Congress to so amend the postal laws so as to include queen bees as mailable matter. Resolved, That the Secretary be instructed to forward a copy of this resolution to our member of Congress.”

Queen rearing was usually done in bee hives. J.S. Harbison published a small book called “An Improved System of Propagating the Honey Bee”. He was granted patent number 26,431 dated December 13, 1859 for his use of what he called “The Vertical Queen Nursery.”

It was fun for me to discover that an electric incubator made here in my town of Petaluma, California, to hatch chicks was used in 1915 to hatch queens. The people at Garden City Apiaries in Chico sent the Petaluma Electric Incubator company a letter telling them, “Last Spring we purchased a small Petaluma Electric Incubator to use in hatching embryo queens. As soon as the cells are capped, they are put into the incubator in small cages and left there until hatched. All our queens are hatched in Petaluma Electric Incubators. We were the first to use electricity for developing embryo queens. We control 5000 acres for the production of honey and the rearing of queens.”

Dr. John E. Eckert reported in the American Bee Journal in November 1962 that commercial beekeeping in California was “definitely on a migratory basis which involve the use of good equipment and long hours of hard work, day and night. The growing season is long, but the blooming period of each crop is generally short so that bees have to be moved from three to five times a year in order to provide adequate pollen and nectar sources and to ‘follow the crops’ for pollination services.” He described the use of mechanized hive loaders and the newest trend to put four to six hives on a pallet. Dr. Eckert also stated it was important for beekeepers to be able to move hives quickly “to avoid disastrous losses from the application of pesticides. California has more millions of acres devoted to an intensive type of agriculture and uses more millions of pounds of pesticides than any other state. In 1958, aircraft sprayed or dusted 5,308, 542 acres using 1,389 planes belonging to 221 firms. Other millions of acres were treated by land rigs.” He said pesticides continue to be one of the greatest hazards of beekeeping in California. These concerns are still being addressed but progress has been made with pesticide application laws and the new hive registration program with the local county agricultural commissioners. For more information and details of this go to www.cdpr.ca.gov/doc/enforce/pollinators/apiary_brochure.pdf.

In 2018 ¾ of the nation’s colonies, 1.5 million, were brought into California to pollinate the almonds grown up and down the Central valleys. California is the only state in the U.S.A. that grows them. Almonds are not a new crop to the state but in the early days all the advice given to the growers was about using various varieties to insure good cross pollination. I found no mention of using honey bees for almonds and other crops until an article in the Pacific Rural Press on May 15, 1915 mentioned an almond grower in the Sacramento area credited his bees for pollinating his trees and said they do it “with a right good hum.” Later I found in the Cal Aggie paper published by the University of California at Davis on January 11, 1918 an article promoting honey bees as pollinators. The title of the article was “Pollination of Orchard Fruits Basis of Test Keeping Bees as Pollen Carriers in Orchard Proves Profitable to Fruit Growers” by Warren P. Tufts. In the article he gives the “common honey bee” credit for being the best carrier of pollen and states it will pay the grower to keep bees even though he might not care to go into the honey business. Interestingly, years before J. S. Harbison said in a letter from his home apiary in San Diego printed in The American Bee Journal’s October 5, 1889 edition, “Fruit-growers generally are clamoring for the removal or destruction of all apiaries in reach of their orchards or vineyards. Their requests are generally being complied with, or the incendiary torch does the work if it is not. I have ‘killed’ and ‘broken up’ over 700 hives of bees within one year, and had about 350 hives set on fire (probably on purpose) within the same period.” He went on to state, “The introduction of bee-keeping in this county in a great measure destroyed the sheep and cattle business, and now in turn the fruit and vineyard industries have destroyed bee-keeping, over a large extent of the county.”

In February 1923 the Sonoma County farm advisor said that it was “evident that bees will supply what has been needed for some time. Orchardists of the county are rapidly realizing that bees are of great value in pollination and with the assistance of the farm bureau, orchardists of the Occidental-Sebastopol section have already contracted for 1,009 colonies to be shipped here from the south.” He advised the fruit men to get their orders for bees in right away. He knew of only 500 more hives that could be secured. The price was $2.50 for the blooming season and the hive owner reserved the right to the honey and would be on hand to care for the colonies while they were in use in the orchards.

In 1947 Dr. Harry H. Laidlaw came to the University of California at Davis. He was a pioneer in the modern technique of artificial insemination of queens. He is considered the “father of honey bee genetics”. His work is being carried on to this day in the Laidlaw facility that was founded in 1969. This bee biology laboratory was renamed in his honor in 2001. It is the largest and most comprehensive state-supported apiculture facility in North America and the only one in California. It provides leading cutting-edge research that focuses on basic bee biology and genetics, addressing international concerns of bee health and meets the needs of California’s multibillion-dollar agricultural industry.

East of the facility is the Häagen-Dazs Honey Bee Haven, a half-acre bee friendly garden that was opened to the public on Oct. 16, 2009. It provides bees with a year-around food source, raising public awareness about the plight of honey bees and encouraging visitors to plant bee-friendly gardens of their own. My favorite thing about it besides the extensive plant knowledge the garden provides is all the art in the garden. The art department worked with the bee laboratory people to make all the works of art biologically accurate. For example, the huge bee in the center is many times bigger than a real bee but in perfect scale.

Research used in writing this article included several historical newspaper articles found at the website www.cdnc.ucr.edu, the Bee Biology website www.beebiology.ucdavis.edu, The Bee-Keeper’s Directory by J. S. Harbison, and American Bee Journal, Nov. 1962, article “Beekeeping in California” by Dr. John E. Eckert, and American Bee Journal, Oct. 5, 1889 page 628 Letter to the Editor.

For a peek into California’s bee forage in 1894 through the eyes of the famous naturalist John Muir go to http://yosemite.ca.us/john_muir_writings/the_mountains_of_california/chapter_16.html.

Ettamarie Peterson, a fifth generation Californian, has been keeping bees on her small farm in Petaluma for the last 29 years. She is currently, and has been for many years, the editor for the Sonoma County Beekeepers’ Association monthly newsletter. She is continuing many years as the Beekeeping Project leader for Liberty 4-H and for the 2020-2021 school year had 15 young beekeepers in the project.

Ettamarie Peterson has recently put together a PowerPoint presentation with more information and is available to share it with associates with Zoom. Contact her at Ettamarie@petersonsfarm.com to schedule one.