By: Mark Winston

Wild Honey Bees

Review of Wild Honey Bees: An Intimate Portrait by Ingo Arndt and Jurgen Tautz, 2022, Princeton University Press

I have a particular fascination with feral honey bee colonies, wherever they may be found; in tree hollows, behind the walls of man-made structures, or in the case of African/Africanized honey bees simply hanging externally from tree branches.

My interest in wild colonies began in South America, where we were studying Africanized bees in the mid-1970’s to determine why they had been so successful since their introduction to Brazil in 1956. Chain saws, axes and hand saws to cut into wild nests; cameras, rulers and weigh scales to record and measure, we carried these tools of feral nest research through the savannas and jungles of French Guiana, Venezuela and Peru, removing and assessing about 40 wild nests. Later, while writing and finishing my doctoral studies at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, we took nests out of houses and barns and the occasional tree, partly for study but mostly because, well, it was challenging and just plain fun to explore the world of feral honey bees.

We recorded reams of data about nest size, number of bees, amount of brood and stores, age of comb and more from the South American and Kansas feral nests. We then transferred colonies into hive bodies, attaching the comb to frames with strapping tape, and kept the hived colonies for research or gave them to local farmers.

I was left with an appreciation for the variety of nest sites and configurations, each adapted to the cavity, external branch or overhang from which the comb hung. I was also left with muscle memory of how strenuous accessing wild nests can be, from tree climbing to cutting trees down to removing exterior walls from houses and barns.

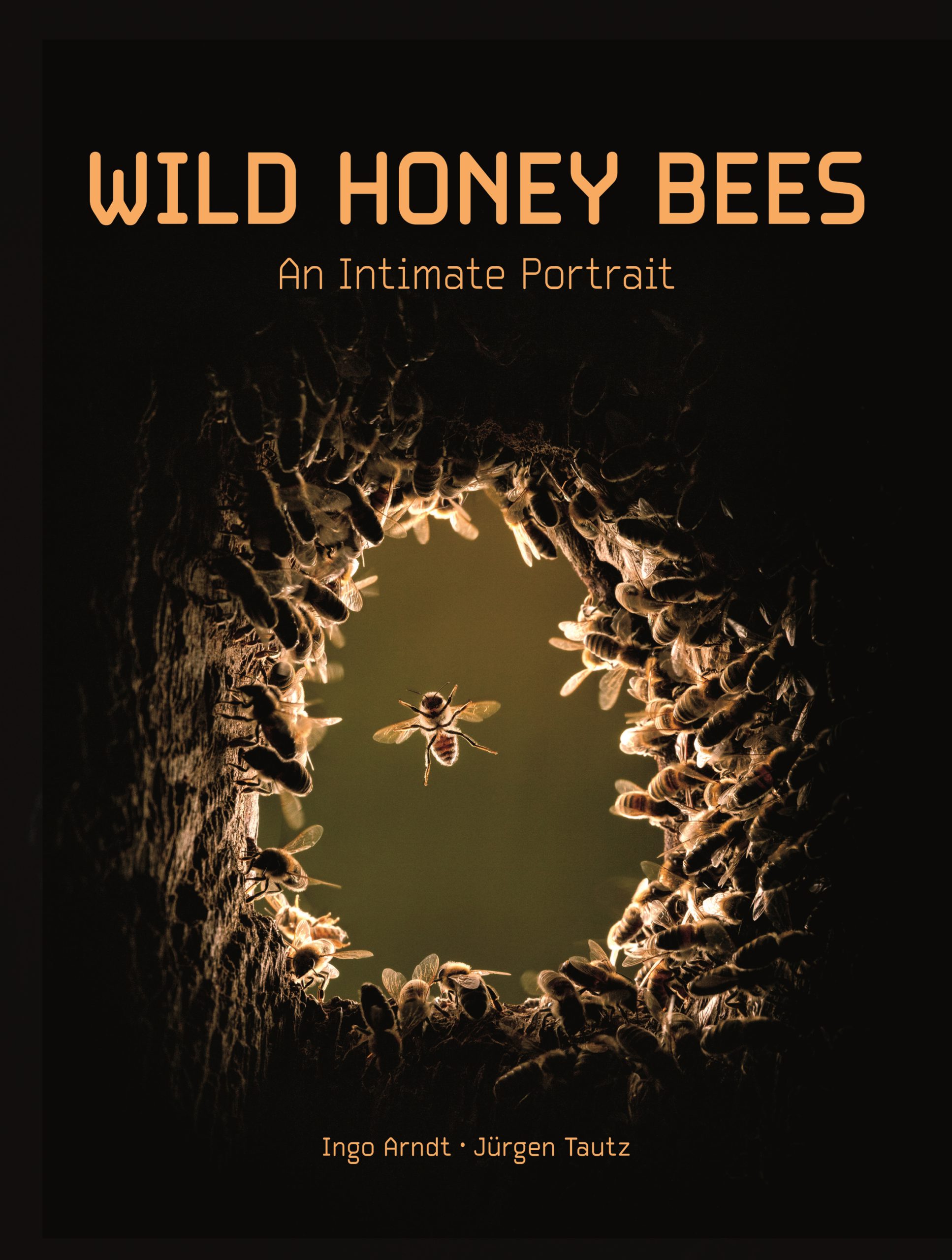

I was reminded of my interest in feral nests when I received a copy of Wild Honey Bees: An Intimate Portrait by photographer Ingo Arndt and biologist Jurgen Tautz (2022; Princeton University Press). This is a glorious book, the best collection of honey bee photographs I’ve ever seen, set in the evolutionary context of honey bee adaptations in wild nests.

The authors are both distinguished in their fields. Arndt is internationally prominent as a nature photographer, his career replete with awards, honors and photographs in major magazines and newspapers. Tautz is a German bee researcher and science communicator, author of a number of popular books about bees.

How Arndt captured bees in photographs is itself a story. As he wrote in the book, “Working with honey bees requires a certain capacity for suffering.” By “suffering” he doesn’t mean only stinging, although he does provide a photo of himself with one eye swollen after a sting. The shoot was physically demanding, requiring climbing trees and positioning himself for many hours outside wild nests. He built an observation lodge high up a tree through which to extensively photograph one wild nest profiled in the book, tolerating oven-like conditions during hot Summer days.

Patience and painstaking attention to details also characterized the eight months and two Summers he spent capturing bees and their forest habitat on film. The project required countless hours to take over 74,000 pictures to choose from in composing the visual story of honey bees in the forest. Arndt also notes the technical measures required for many of the photographs, including use of a high-resolution 50-megapixel single lens reflex camera, and macro and magnifying lenses to create images that could print out clearly on a full page.

I can not find enough superlatives to describe the photographs in Wild Honey Bees. “Spectacular,” “Gorgeous,” “Stellar,” “Stunning,” are only a start. The close-ups of individual bees are detailed in a way that bring home the complexity of honey bee anatomy, with each hair, eye lens, mandible and sting standing out in sharp delineation.

The images also provide insights into the behavioral adaptations that have made honey bees favorites of insect aficionados for thousands of years. Among my personal favorites are a crisp photo of the queen laying an egg, surrounded by her attendants; water collectors with tongues extended, slurping up liquid; two worker bees guarding the nest’s entrance, mandibles open to attack invaders; and a ball of worker bees surrounding and killing a wasp attempting to pillage the colony.

All of the photos were taken in and near feral nests in Eastern European forests. The framework for the images is delineated in the text, loosely organized into chapters about social behavior, other organisms that live in wild colonies, defense, forest habitat, and honey bee orientation. The final chapters include a series in which a swarm colonizes a former woodpecker nest, and a short bit about traditional forest beekeeping in which colonies are left intact but villagers living nearby regularly remove a few combs of honey.

Wild Honey Bees should become a part of every beekeeper’s library, as a visual reminder of the feral origins of our managed insects, and of their stellar beauty and elegance. The text and photographs remind us that forests were the original habitat for European honey bee subspecies, and the authors call for conservation of what remains of these unique habitats. Arndt and Tautz also ask us to notice that honey bees in the wild are threatened in many parts of the world, including European forests.

The authors chose not to engage with the context of beekeeping today, or to provide a comprehensive discussion about the biology of feral honey bees, maintaining the book’s focus on the photographic images. Perhaps the old adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” applies here. Still, more depth in the text would have been welcome; readers interested in a deeper dive into what we can learn from wild nests about honey bee biology and the future of beekeeping might obtain Tom Seeley’s most recent book The Lives of Bees, also published by Princeton Press.

I was astounded at the book’s low price, considering the excellence of the photographs and the book’s high production qualities. This is a hefty coffee table book that you would be proud to display in your living room, but priced at only $23.00 to $29.00 dollars, depending on where you purchase it. Similar books are usually two to three times the cost, so I can only assume the authors and publisher are keeping the cost low as a public service rather than to generate a profit.

I particularly enjoyed Wild Honey Bees because my relationship with wild nests has become vicarious since I moved to SFU and coastal British Columbia, Canada 42 years ago. I had expected a wealth of wild colonies to remove from trees and houses, as the Vancouver area where I live experiences a much milder climate than the rest of Canada. I thought I’d find many opportunities to immerse myself and my students in feral nests.

Not so; I’ve yet to find or be told of a single wild honey bee nest. I learned the reason early on; while our winter temperatures are mild, rarely dipping below freezing, there is a floral dearth in May and early June. Earlier in the season, colonies thrive on Spring nectar sources such as maple and dandelion, and grow well, perhaps swarm, but then crash in late Spring as there’s not enough nectar in the field to sustain colonies or the swarms they issue. Managed colonies must be fed to get them through this dearth period, but feral colonies have no such options.

Whatever your role in beekeeping, or if you’re a civilian outside the beekeeping sphere, Wild Honey Bees will enhance your pleasure and interest in these most fascinating of creatures. And perhaps, just perhaps, readers will be inspired to do whatever they can to preserve wild honey bees, myriad other wild bee species, and the healthy habitats so critical if both wild and managed bees are to survive and thrive.

Mark L. Winston is a Professor and Senior Fellow at Simon Fraser University’s Centre for Dialogue. His most recent books have won numerous awards, including a Governor General’s Literary Award for Bee Time: Lessons from the Hive, and an Independent Publisher’s Gold Medal for Listening to the Bees, co-authored with poet Renee Sarojini Saklikar.