Mark Winston

Mark Winston

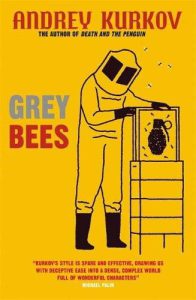

The recent full-on Russian invasion has focused and heightened attention on Ukraine and distinctive aspects of its culture, among other things bringing Ukranian writers to wider attention. Grey Bees, by Ukranian author Andrey Kurkov, is one recent Ukranian novel that has been working its way up the bestseller lists, in part because of the invasion, but also because it’s quite a good read.

Grey Bees was first published in 2018, with an English translation by Boris Dralkyuk published in May 2022. It was written after Russian troops invaded Crimea in February 2014, which then declared its independence from Ukraine, while pro-Russian separatist forces in Donbas, a region in eastern Ukraine, continued to battle with the Ukranian military. The separatists were and continue to be supported by Russia.

The book opens in the grey zone, the contested area in Donbas between separatist and Ukranian forces, a few years before the current country-wide invasion. The main character of the novel, beekeeper Sergeyich, is one of the last remaining inhabitants in a small and mostly abandoned grey zone village, from which most of the residents had fled. To be clear, this isn’t a book primarily about bees or beekeeping, but rather uses bees as a plot element to get Sergeyich moving across the regions, and as a thematic element upon which to hang the book’s exploration of the impact the war has had on its human victims.

Grey Bees follows Sergeyich and his six honey bee colonies from his village through the grey zone border into Ukraine, then across the Russian border into Crimea. He’s moving his bees so they can forage in a more peaceful location.

Beekeeping, and attitudes about bees, feel quite different in Grey Bees than the North American norm. For one thing, Sergeyich only has six hives, yet his most prominent personal identity is firmly as a beekeeper. The honey his bees produce is more valuable than North American honey, in part because banks and the post office are non-functional in the grey zone, and cash is hard to come by, so Sergeyich uses his honey to barter for food and petrol.

Sergeyich trades some jars of honey for food at a local grocery store after he moves his bees into Ukraine. The store owner invents a unique value-added marketing strategy, adding stinging nettles to the honey. She then sells it as an anti-alcohol treatment to help customers sober up, and jacks up the price. Based on the copious drinking of vodka represented in the book, I suspect that honey jumped off the shelves.

Honey bees are instilled with personalized and therapeutic qualities in Grey Bees, and beekeeping inbued with folk traditions. One ongoing motif in the book is Sergeyich grouping his colonies and placing a board covered with a thin mattress across the hives so that he and others can sleep on the bees.

Before the war, customers would come from all over the region and pay Sergeyich for the opportunity to nap on his hives, believing sleeping on top of the bees was relaxing as well as curative for countless ailments. Sergeyich himself wakes up one morning with no feeling in his left arm, and rather than go to the hospital for medical attention he spends the next night sleeping on his bees, waking up cured.

Kurkov addresses the dimensions of why we keep bees, and how, which in North America tends more towards the utilitarian and productive than the spiritual. He writes of Sergeyich’s light-touch management philosophy:

He wasn’t merely the owner of an apiary – he was the representative of the legitimate interests of its bees. The bees, of course, had just one interest: gathering nectar and pollen. Sergeyich regarded the internal rules of their life (relations between the worker bees and the drones, all that petty, everyday nonsense) to be their personal business, the same as with people… They never asked his advice on what to do or how to do it. They didn’t need his advice, or his permission.

The title “Grey Bees” is a double entendre, referring in part to Sergeyich’s home apiary being in the grey zone, but also to the grey, or mountain, bee, a honey bee type found in the Carpathian Mountains, ranging through central and eastern Europe, including Ukraine.

Beekeeping in Ukraine has a long and storied history, including the notable Petro Prokopovych, generally credited with inventing the first movable frame hive in 1814, as well as the queen excluder. Today Ukraine is one of the top five honey producing countries in the world, and reports 400,000 beekeepers out of its total population of 46 million people.

There doesn’t seem to be a scientific consensus about whether the Carpathian honey bee is a separate subspecies, Apis mellifera carpatica, or a variety of carniolan, Apis mellifera carnica var. carpatica. However the taxonomists dice and slice it, the Carpathian and carniolan bees have similar characteristics, including a dusky greyish colour. Both types are reported to Winter well in cold climates in small clusters, with brood rearing and adult populations expanding rapidly in the Spring. They are also reputed to be hygienic, resistant to pathogens and gentle.

North Americans tend to be less obsessive about the subspecific purity of queens than European (including Russia and Ukraine), British and Irish beekeepers. I have heard passionate arguments when visiting those countries concerning if and how to maintain honey bees with local genotypes; if you want to hear the Irish at their most voluble, just mention the Irish Black Bee among beekeepers at the pub, and duck.

American and Canadian beekeepers generally are less excitable about honey bee genetics, perhaps because honey bees are not native to North America, and our bees are mixed lineages. Still, some pure lines are maintained by North American breeders, with carniolans being of particular interest.

The Carpathian honey bee has recently attracted some attention in Canada, which has a cold climate and short Summer season similar to the Carpathian Mountains. Canada imports queens under permits from only a few countries, including the United States, Malta, New Zealand, Chile, Australia, Italy and Ukraine. A Canadian beekeeping operation, Niagara Beeway, has been importing Carpathian queens the last few years, in the hopes of servicing the market for queens and package bees in the coldest Canadian beekeeping regions, particularly those with short growing seasons. They also sell to queen breeders, who have been experimenting with various hybrid combinations of Carpathian, Carniolan and Italian bees.

The Russian invasion prevented most importations in the Spring of 2022, although a few queens made it out of Ukraine into western Canada. This past Spring the Carpathian Valley, where Niagara Beeway’s queens were reared, has been the scene of intense hostilities, and two of the drivers for the Ukranian apiaries who were returning from the airport with donated medical equipment were shot.

According to George Scott, head of Niagara Beeway, the Russians have been specifically targeting any Ukranian business with income from abroad, and it’s simply been too dangerous to make the seven-hour drive from the Carpathian Valley to the airport where the queens are usually shipped. However, the war in the west has now shifted to the eastern Donbas region, and Scott is hopeful there will be a queen shipment to Canada this July.

The toll the war in Ukraine has taken on beekeeping is but a sliver of the daily tragedies represented in Grey Bees. Still, Kurkov’s Sergeyich finds some solace in his bees, their behavior making more sense to him than that of the people around him.

There are some lovely passages in the book imbuing bees with their own clarity of purpose, contrasting with human behavior. Let’s give Sergeyich the last word:

Bees don’t understand what war is. Bees can’t switch from peace to war and back again, as people do. They must be allowed to perform their main task – the only task in their power – to which they were appointed by nature and by God: collecting and spreading pollen. That’s why he had to go, to drive them out to where it was quiet, where the air was gradually filling with the sweetness of blossoming herbs, where the choir of these herbs would soon be supported by the choir of flowering cherry, apple, apricot and acacia trees.

Mark L. Winston is a Professor and Senior Fellow at Simon Fraser University’s Centre for Dialogue. His recent books have won numerous awards, including a Governor General’s Literary Award for Bee Time: Lessons from the Hive, and an Independent Publisher’s Gold Medal for Listening to the Bees, co-authored with poet Renee Sarojini Saklikar.