Jessica Louque

I’ve seen a lot of unfortunate misidentifications of bees lately. It could be because I work with honey bees on a daily basis, so I am always on the lookout for bees, or maybe it’s because bees are so popular right now. Either way, I can’t tell you the times there was a picture of a “bee” and it was a hover fly or a leafcutter bee or a wasp. Even at my own state beekeeper meeting had a syrphid (hover fly) picture greeting all those checking in to the meeting! The bee exhibit at the zoo is also depressing. The place that is supposed to teach the public about bees has approximately half their display photos incorrect – how embarrassing! Does anyone fact check anymore?

Speaking of embarrassing, we had an incident where our youngest kid didn’t know the difference between a honey bee and a yellow jacket, although it was stressful circumstances. We went hiking for the weekend, and decided to take an advanced trail (gluttons for punishment at this point, camping with four kids) and ended up stomping through a yellow jacket nest. Poor George had them stuck in his clothes and chasing him, and was screaming at the meanie bees. I later explained to him that yellow jackets were not bees, but they were wasps and meanies who eat bee babies. When we came home from the trip, we fire bombed a nest in our backyard as retribution.

Since we needed a family education on different types of bees and wasps and flies, and we currently have a family vendetta against yellow jackets, we’ve been doing a little research on wasps and bees. Hopefully everyone has learned something about them besides how much the stings hurt!

Yellow jackets have several names, and a lot of them can be used for totally different insects. The actual yellow jackets (here at least) are the Vespula squamosa species, which are the Southern Yellow Jacket. Sometimes they are called ground hornets since they can nest underground. Another common name for them is meat bees. I particularly enjoy this one. It is one of the biggest differences between bees and wasps. Bees are not carnivorous, and get their protein exclusively from pollen sources. Wasps and yellow jackets both feed their babies meat.

A yellow jacket queen is the only part of a colony that overwinters. In the Spring, she raises her first batch of babies by herself. The newly emerged workers will take over the household duties, including taking care of their siblings. Only the larvae eat meat, so the workers go out and hunt down other insects, like caterpillars. Technically, yellow jackets are beneficial insects because they prey on pest insects. They will pick up the chubby little caterpillars, chew them up, and then feed them to the hungry children. Later in the Summer, the hive builds up, anywhere from several hundred to several thousand adult yellow jackets. This is when the queens for next year and the drones are being made. The colony will take care of them until Autumn when they leave to mate and find a place to overwinter. In the meantime, their usual food, caterpillers, has disappeared, and they still have children to feed. It’s during this time that they really become a nuisance to people. They start foraging in trash, eating from tables, following people around – come to think of it, they sound a lot like dogs. I’ve never been stung by my dog, but she does have pretty vicious farts. I guess at this point they’re both desperate for food and don’t realize they are being annoying.

Aggression is a common trait among the wasp families, although the yellow jacket is considered one of the most aggressive. This is likely due to the underground nesting habits of the local populations. If a nest is in the air, there’s a lot less of a chance that you’re going to disturb them. However, if you’re walking around, or in our case, hiking (stomping) through the woods like a pack of ungainly elephants, you’re going to be getting some incredibly unhappy visitors quickly. Yellow jackets are super awesome because not only can they sting multiple times, but they also will mark you with a scent so that all their friends know to hunt you down. It’s really sweet of them, like giving you a present that had a lot of thought behind it. I have a friend who did some grad school work with yellow jackets and he informed me that if he was ever marked, he had to wash his clothes several times to remove the odor. It smells a little similar to the angry honey bee smell, which to me is like an artificial banana smell – not an actual banana smell, but if you rolled yourself in banana runts candy. Of course, if you can smell the marking, it’s probably time to run away (if you’re not already).

One of the more important (for me) aspects of life with yellow jackets is: how do I get rid of them? I am not normally an “ew kill it!” type of gal, but in the case of yellow jackets I feel that it’s more of a preventative measure, or a revenge prequel, to kill a nest. These rank up in the line of hate with mosquitoes, ticks, and roaches. They’re not cute, cuddly-ish (like a baby bee that just emerged from it’s cap and looks like a teddy bear – awww), or remotely friendly. As I said earlier, we had an unwelcome residency in our backyard, which we literally stumbled over earlier in the Summer. It mostly became overlooked for the year until the hiking incident, when it became the focus of the revenge plot. We’ve had a rough time with yellow jackets at the house because of the honey bees. It seems like having hives of bees around is like a McDonald’s to the local predatory insect population. We have hordes of robber flies, wheel bugs, spiders, and of course, yellow jackets. They all pick off bees or larvae like it’s a drive-thru window.

Populations build up fast for all these predators, who also have plenty of non-bee food sources as well. I like to watch most of these, but the yellow jackets are always concerning. Last year, I had to kill a nest at my neighbor’s house to keep them from coming here (the yellow jackets, not the neighbors) and also to keep the neighbor from getting attacked while he was doing some yard work.

At our house, we like to do ordinary tasks with pizazz. We thought about lighting fireworks on top of the hive, but we figured we’d just blow through a window in the house and catch the roof on fire. We also don’t really use any pesticides here unless it’s a biopesticide (something like Bt), so we were trying not to spray Hot Shot or Raid or a comparable bug killer. We compromised the fireworks display with gasoline and fire. I was not amused with pouring gasoline in the ground, but we tried a little bit of lighter fluid the night before and burned it for a good 10 minutes. The next day, we went to check on the hole, and about six inches over, they had razed an area of grass and dug an even larger hole. At this point, I think we (Bobby) might have poured in a cup or so of gasoline and lit it on fire like a torch from the hole with a paper towel. It worked really well like a candlewick or an oil lamp. There were a few stragglers the next day, but it didn’t appear that there was a new hole anywhere. Thus, we declared success over our enemies.

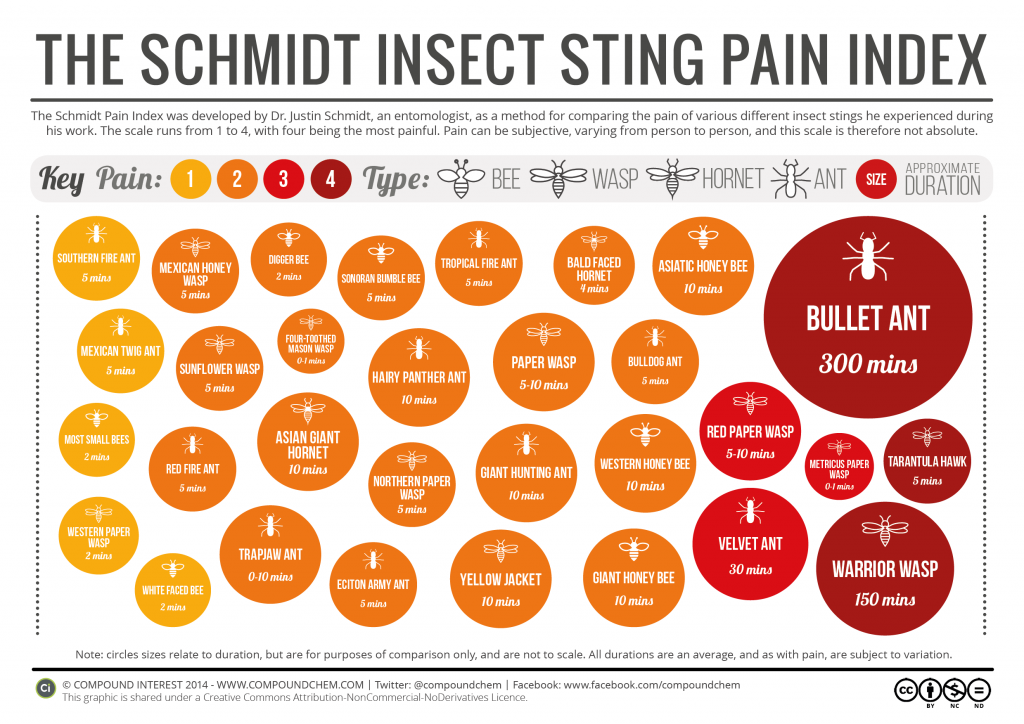

Fortunately for everyone, yellow jacket stings are not going to kill you or anything like that, unless you are one of the very few people who are allergic to venom in a way that stops your breathing (as opposed to what everyone else considers “allergic” where it hurts a lot and it swells and some people get all whiney). On the Schmidt Insect Sting Pain Index, honey bees and yellow jackets score the same Level 2 on a scale of 0-4, with 0 being the stinger doesn’t break the skin, and 4 being a bullet ant. If you were wondering, bullet ants are so aptly named because it feels like being shot. Now, in my personal opinion, bee stings hurt a lot, yes, but a yellow jacket is a much more burning, intense pain that stings for days. I don’t show any signs of being stung at all after about 10 minutes, but if something touches me in the general vicinity of a sting, I get all crabby (Bobby is the same way, including the crabby). The kids get these big blotchy red patches that swell up and last for a week or two. I guess the venom from thousands of honey bee stings works a little bit on yellow jackets. Too bad it doesn’t reduce the amount of pain too!

I hope everybody has picked up a few interesting things about yellow jackets. I know in our family, George in particular, has taken a keen interest on his newly forged arch-nemesis rivalry. Maybe one day we can all coexist in peace and harmony – but until then, keep the gasoline and the blow torch handy!

Jessica Louque and her family are living off the land in North Carolina.