Jim Tew

http://www.onetew.com

By: James Tew

Talking and writing about bees – modern beekeeping minefields, and comments on dealing with old frames.

Talking and writing about bees – cursed either way

Every month, I get several beekeeping magazines. Sometimes these publications accumulate after only being quickly reviewed. At other times, I read every word. I always enjoy the read and have enjoyed it for many years. Bee publications literally litter my life. But, regardless of the amount of attention that I devote to a particular monthly magazine, I usually get a pained, slightly uncomfortable feeling as I put the publication aside.

“Wow – great article with great graphics!” “Well . . . I had not thought of that – and I should have.” “Why do my photos never look this good?” “I wish I could voice an opinion that cleanly.” Even when I pick up new information or new techniques, I still have a small, distant darkish feeling that I should be doing more, learning more, and staying more updated.

Yet, it is even a bit worse. For all of us senior citizen “white hairs” who spout, “Well, when I was a young bee boy about 107 years ago, that is not how we did it. You should have been keeping bees then!” This sage beekeeping attitude will not always carry the day. Beekeeping should not be trapped in the past.

Many of the new writers that I read today are intelligent, well read, and usually brimming with confidence and opinion. I envy them. In my defense, many years ago, it was much easier to professionally communicate about bees (or maybe I was just brimming with confidence and opinion). The old/wise card plays out very quickly.

Today’s audience, either live or virtual, has access to a vast, vast amount of information on all aspects of beekeeping and the philosophy of life. New beekeepers are not the clean slate that they were decades ago. It is very easy for any professional bee communicator to get tripped up when addressing eclectic modern beekeeping groups.

For example

Several years ago, a knowledgeable beekeeper wrote me after having read a piece I did on smokers and smoker fuels. Within the article, I commented that, “I wished someone could develop a better system than just primitively smoking a bee colony” (and everything else surrounding the colony).

I went on to mention that pine needles (pine straw for those in the Southeastern U.S.) is a common fuel. It ignites easily, puts out a cool white smoke, and is readily available. It also burns fast and requires frequent recharging. I commented that such smoke residue clings to everything. The beekeeper, the vehicle, the storage shed – all smell of pine smoke. Actually, nearly any other smoker fuel leaves such an odor.

The writer explained, in a concise chemical way, that pine needles contained several resinous byproducts that are inhaled when we burn it in our smokers. As a smoke alternative, other (apparently) safer fuels, such as wheat straw, were suggested by the writer.

At the 2017 Winter New Jersey Beekeepers’ Association meeting, I said that oxalic acid sublimated fumes should not be inhaled (this is true), but neither should bee smoker smoke be casually inhaled (this is true). I went on to say that due to its resinous components; pine needle smoke should especially not be used as smoker fuel (to an extent, this is true, too). It was an uneventful moment, and I moved on.

Later in the day, as I strolled by the equipment vendors, I noticed that one of the vendors had bags of pine needles for sale at their equipment table. (Drat!). I had stepped on a small bee mine. To that NJ vendor, let me add this caveat. Through all the bee years, untold amounts of pine needles have been burned as smoker fuel. Obviously, the diagnosis of “death due to pine needle smoke” from a bee smoker is non-existent. Was I suggesting that while standing on mats of readily available fuel, beekeepers in pine-growing areas should search for another fuel? Not at all. Essentially no smoke fumes are good for us or our bees, particularly pine smoke. But for most of us, the exposure is (apparently) slight, and we should simply use the least amount possible. I was correct, but it was a small correct assertion.

To the vendor in NJ, I apologize. My assertion was too powerful, and if I use it again, I will soften it.

For Example (#2)

At a recent meeting, I extemporaneously said that beekeepers had changed in recent decades. I colorfully said that they no longer come to bee meetings wearing bib overalls and driving a tractor. Of course, I later noticed that an accomplished and educated beekeeper, whom I have known for many years, was sitting right there with bib overalls sans tractor. (Drat!). I meant that as a colorful analogy and was not even aware of what the beekeeper was wearing. To that beekeeper, I apologize. I hope it was patently obvious that I was not referring to him in that context.

For Example (#3)

A couple of years ago, I was an eager bird feeder. I enticed a host of interesting bird species and about 9,000 house sparrows. Then the squirrels came. Then the skunks and raccoons started the night shift at my feeder buffet. It became a veritable wild kingdom. All I had wanted was some yellow finches, some Rose-Breasted Grosbeaks, and rarely, a few Pine Siskins. Yet, here I had this menagerie of wildlife.

The skunks particularly went wild. At one time, I had six to eight skunks living under my small storage shed. Of course, they found my hives. I had a real imbroglio ongoing. I had skunks running wild, but not very wild, for they were not really fearful of me. Later while trying to relocate a raccoon that had been harassing my colonies, I got a skunk instead.

At a subsequent meeting a week later, I (humorously, I thought) said that, “If you have a skunk in a live trap, you have no friends – anywhere!” Immediately, an individual in the audience stood to reprimand me for “skunk mistreatment.” She said the skunks were there first, and I moved in on top of them when my house was built. She was forceful in her beliefs (Drat!). I had a notion that this woman did not have six to eight skunks within 50 feet of her back door with six grandkids, two dogs, and a cat.

I had no idea that there were skunk-loving people and groups within this country. I stopped feeding birds. Now I have very few skunks, raccoons or birds.

It may not be what’s said or written, but rather what is NOT said or written

In this bold, restructured bee world, it is not always what is said during a presentation or written in a published article – its what you didn’t say.

I recently returned from a nine-day “bee talking” trip. I presented nine times so I can’t recall the particular meeting where a beekeeper came to me and directly asked the question, “Why do you never write about top bar hives?” Did I sense that he could have been braced for an argument?

I am not opposed to TBHs in any way, but I have not used them in many years. I built three many years ago and stocked them here in OH. As they died out (something not unique to TBHs), I did not replace them.

My main experience was with East African transitional top bar hives in Uganda and Kenya. Then later, I worked with Africans who were part of my program. At this point, I don’t have a strong interest in them – so I have not written much about them. I have every intention of restocking them one day.

My point?

I could go on, but hope that I have made myself clear. Nothing is wrong with today’s beekeeping informational systems. Indeed, the mechanisms keep beekeeping diversified and evolving. As a presenter or writer, one has to take greater care when speaking casually or professionally than speakers did many years ago. The average beekeeper is now much better informed and has frequently formed solid opinions based on the available information – sometimes even before becoming a beekeeper. Be prepared to discuss all points and recommendations in depth.

What do you do with old frames?

Is this what you do with old frames? This one was tossed onto the woodpile. I only had one that was in dire need and at the moment, I was engrossed in beehive work. Maybe later in the season, but “later” has yet to come.

It would be easy to hate these failed things. They take up space, they require tedious labor to repair, and they attract mice and insects in storage. Many are still wooden, but increasingly, many of these needy frames are made of plastic. Essentially, each of these frames signifies a failed effort on both my and my bees’ part. Maybe that is why the task is distasteful.

Unless you are of a personality who enjoys the frame repair process, I would (reluctantly) recommend using plastic sheet foundation (inserts) for repairing wooden frames – even those that had been wired. Much like a wheat penny, wired frames are yielding to newer types of frame and frame assembly. Most wired frames would be very old frames. Common sense dictates if the antique is even worth repairing.

I did not look at every supply catalogs, but I found it surprisingly easy to find all the necessary replacement parts to completely rebuild a traditionally wired frame or even assemble new wired frames. I would have thought that these assembly products would be fading away. I’m happy they are still here. Could I ask if any of you still nail, wire, and embed wax foundation in wooden frames? And if you do, would you tell me why you still do that? Obviously, there is absolutely nothing wrong that that option. I refer to this process as traditional frame construction.

Whatever it takes

In articles past, I have tediously described how to partially disassemble a failed wooden frame in preparation for reassembly. I’ll not go through that again. If you have an interest in repairing a wooden frame, you already have a pretty good idea of what the task will require. Use a heat gun to melt residual wax and propolis. Have cutter pliers handy. A light hammer, frame nails, and a fresh bottle of wood glue are required. A table saw is great for cutting new wedges for the top bar. Alternatively, if not destroyed or rotted, just use the broken wedge and nail/glue back into place.

A common challenge

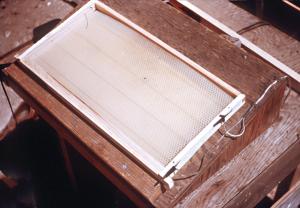

A frame with foundation with wiring about to be embedded. Note that the foundation is in a frame having both top and bottom pieces without grooves. The foundation is held in place only by the wiring.

You, the frame repairer, can count on challenges when retrofitting a different style of foundation into a frame that was not originally intended for that foundation type. Improvise, but I hope you don’t get sloppy. Use snips to cut plastic inserts to fit. If replacement foundation is too small, tack it in place with frame nails or whatever else you can contrive. Once the bees have the refurbished frame and are on a good nectar flow, they will generally cover over all your improvised repaired areas.

A new common challenge

Plastic frames require more repair finesse. Forget gluing various hurt parts and spots. The propolis and wax will make glue use impossible. If the frame lugs are broken, repair parts are available that will replace them. This small metal piece was developed for wooden frames, but I suspect it could be screwed to a broken plastic frame that needs a lug repair.

Jimmy C., an AL beekeeper, says he takes unusable plastic frames, puts them in a large container and waits for the wax moths to find them. After they have broken down as much comb as possible, Jimmy uses a pressure washer to clear as much of the remaining debris as possible. After drying, he lightly coats the (mostly) cleared frame with bees wax and reuses the frame. I can see where that would work. I have used a pressure washer to refurbish wooden frames. You will need to solidly clamp the frame to something or it will be blown to the next county. Additionally, the repair person should expect to be wet from the ears down – but the frame will be clean.

End note . . .

I very incorrectly assumed that wired foundation was rapidly being replaced by anything plastic. So – I should make a video of the process before it is lost to beekeepers everywhere. I took a look at the video storage sites just to be sure. I’m glad I did, it would appear that, in fact, most beekeepers must have made a video on how to wire frames and embed the wiring.

I have essentially moved to plastic and can readily say that there are traditional issues with both plastic frames and plastic inserts – but they are so fast to put together. For the second time, I would like to ask you how many of you are still using wooden, wired frames, and why? I know this frame is stouter and more stable, but do you have other reasons.

Thanks for reading . . . Jim