James E. Tew

Stay Connected

http://onetew.com

By: James Tew

Well, is it European Foulbrood or not?

Comb – much more than a hive product.

Odds and Ends – Adding wax to plastic foundation.

Well, is it European foulbrood or not?

As I was preparing to depart for the 2017 Heartland Apicultural Society (HAS) annual meeting in Evansville, IN, I took a quick last look at two colonies that I have temporarily put behind my shop. Just a day before I had transferred these two colonies from nuc boxes to full deeps. Queens that were purchased for $35 each headed these two units. I bought two queens from the same producer last year and found them to be absolutely great. I was expecting the same this year, but – no – I found that both of these colonies were filled with European foulbrood (EFB).

Beekeepers, I have not seen true EFB in decades. Indeed, in several previous articles, I have asked what happened to this old annoying, but manageable disease? Well, here it is, in two nucs headed by $70 worth of queens. This was a true surprise immediately followed by sentiments of both disappointment and annoyance. By now, these two should have been beautiful colonies.

Could anything more happen to these two units? Yes, it could. As I was looking and wondering about these afflicted colonies, I began to see clear signs of robbing behavior at the hive entrance of one of the beleaguered colonies.

Ironically, this destructive activity is not new to these two nucs. I made the nucleus colonies in my home yard, which is about 75 yards away. A day later, I was having a beeyard walkabout and discovered that these two nucs were under heavy attack from their unfriendly neighboring colonies.

Note to you and me both – if only a weak nectar flow is underway, be very careful when making up nucs in a yard that has other powerful colonies. Under dire conditions, any food resource is fair game to any bee colony. Robbing becomes probable. Small colonies are vulnerable first.

As reported above, I moved the two bullied nucs to a new location behind my shop and reduced the entrances. I essentially hid them in the foliage canopy of large day lilies. I thought I was being sneaky, but I suspect that the robbers knew exactly where these small colonies were relocated. I do not know how robber bees do this, but they seem to always know such things.

I put top feeders on each of them and gave them some pollen substitute. What a good beekeeper I am! I fed them regularly and gave them their space. Good queens. Good food. Protected location. Loving care. These nucs were going to be beautiful. I gave them undisturbed weeks to develop. Yet here they are presenting unexpected problems.

A question for you and me – Could this extreme pollen shortage have been the stress factor that allowed EFB to express itself?

An aside…

I could not ignore the robbing threat. I could have dead colonies and disease spread to boot. Both colonies had EFB and both were under attack. When I was rummaging around for something to serve as entrance reducers, I remembered that I had two new, unused entrance devices that prevented robbing behavior.

I am not endorsing nor promoting, but these devices have worked very well. They were quick and easy to install. I put them on the colonies that were under attack and, with little time left before departing for HAS, I wished both of them good luck.

Upon my return four days later, the robbing prevention devices had worked and all was quiet.

No pollen – at all

While I was wondering, tinkering, photographing and pontificating, I noticed that there was NO pollen stored anywhere in these two colonies or young larvae. There were only eggs, older larvae and some emerging adults. These colonies did have a lot of open cells and dead/dying larvae. I gave both colonies pollen substitute in an attempt to address this issue. I wonder how my large colonies are faring in my apiary about 75 yards farther back. Were they, too, pollen deprived?

Am I sure that this is this really European foulbrood?

Since I last saw an EFB infection many years ago, Bee Parasitic Mite Syndrome (BPMS) has become common. If Varroa infestations are not treated, the affected colony can abruptly collapse. Several years ago, I had that happen to one of my colonies. Initially, BPMS looks a lot like American foulbrood, a much more serious affliction that European foulbrood. It can also have attributes a bit like European foulbrood.

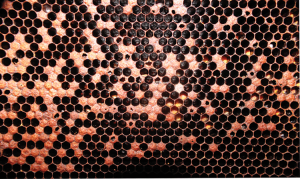

This looks like EFB to me, but I am only highly confident – not totally confident. My colonies have a sour odor, brownish twisted larva and a spotty brood pattern. There are a few punctured cappings, but nothing like the photo showing BPMS. There are some Varroa present. That is to be expected, but there is nothing like the number of visible Varroa present in a colony that is collapsing from BPMS.

So, send samples to the USDA for analysis – and then wait

I will, but I will not have my results for a while. Not wanting to just sit on my gloved hands, I would dearly like to do something while awaiting confirmation. Adding pollen substitute, preventing robbing, and possibly adding a frame or two of young open brood would possibly boost the sick colonies.

Even if I can get the colonies back to good health, the queens’ progeny were clearly susceptible to European foulbrood. How far should I go to save these expensive insects? EFB is said to be a “limiting” disease. It does not normally kill the colony, but keeps it weak and unproductive. However, I did pay a lot for these insect monarchs, and they are healthy looking in every way as they roam around their diseased brood nest.

This ongoing queen thing….

Not now, but in a future article, I will spill my frustrated comments about the current state of queen affairs – their expense, their unpredictable productivity, their difficult installation process, and the problem with quickly acquiring replacement queens. Buying, installing, and evaluating queens are not what it was a few decades ago. Queen replacement has always been considered major colony surgery, but now the queen replacement procedure is even more demanding with added significant consequences.

Honey bee Images

The imaginal stage of honey bees is the adult, sexually mature, stage. Somewhere in my entomological training, I thought I was told that an imago was a new adult – brand new – but the word is simply another term for the adult stage. While I was photographing the various EFB pictures, workers would emerge from their incubation cells. I suppose it could be sappily said that these bees were “baby” adults. In fact, they do have a distinctive look and recognizable behavior.

The big difference is hair, lots and lots of it. It causes their eyes to have a strange black-dot-look rather than distinctive eyes. In the larger format of the pic that I have here, I can see that the head hair and the eye hair cover much of the compound eyes as to make them only half visible. The three ocelli (eye spots) that are on top of the bee’s head, centered between the two compound eyes, are totally covered by soft curly plumose hair.

A new adult bee’s color is washed out – nearly translucent – even bland. These bees are feeble, but clumsily active. They are hungry and will immediately begin to check cells. I suppose they are looking for food. I have read that such young bees must learn to solicit food from other workers, and until they have the begging technique down, they don’t get fed. Seems harsh.

Capturing micro photos takes a remarkable amount of time. This means that, while setting up and releasing shutters, I have the opportunity to watch various comb behaviors in real time. As I have watched these baby adults, might I offer a radical suggestion?

Comment to you from me – While taking macro shots of bees and combs, I have begun to notice small details that are missed by a simple perusal of the combs. The macro shot stops the action and gives plenty of time for close – even very close – looks at various activities. I love it when these surprises turn up.

Cell cleaning is cited as the first task a bee performs1. I would suggest that the “immature adult” stage is the first adult stage. To be more dramatic and to include a technical tone, maybe I would suggest “immature imago” but I’m just kidding you with that suggestion.

Seriously, these immature adults cannot fly. They are clumsy but mobile. They have much (so much) hair on all their eyes and ocelli that limit their acuity. They lack chitin or the hard outer body covering. They could be compared to soft-shell crabs. They are essentially unable to sting, and I suspect that most of their glands are only beginning to function. They can barely feed themselves. Looks like a bona fide stage to me. Their first assignment is to grow up.

Royalty Crown Work Box2

The Royalty Crown Work Box opened showing the queen port open, as well as the ventilation hole. The upper entrance is the cube shown in the lower right of the photo.

I recently began to use a device that is positioned atop the hive. I make the usual statement: I am not making a general endorsement, but simply telling you what I am using, and how it is working.

It is a multipurpose box that provides creative space for several tasks. Some of the reported uses are: releasing or storing queens and providing a top entrance/exit. It has a removable section that allows the beekeeper to see the top frames without having to open the colony. The device comes with a small, plastic feeder, and there is an entrance (a large hole) near the center that can be used to give the bees access to the interior of the box. Alternatively, it can be closed.

Queen storage and introduction

Though the box can used to feed pollen substitute, I particularly like the potential for storing and introducing queens. Frames of open brood will need to be directly below the queen cage.

While I only have a single box and cannot make broad judgments, the colony that I have the box on has been agreeable and calm as I opened the colony. Normally, I do not use smoke and gloves are not needed. Please note that this calmness may only be a characteristic of this colony or to an ongoing nectar flow.

Opening the Royalty Box floor

Using the hive tool to pry against the two screws (one is shown in the photo) allows the floorboard to be easily and quietly removed. It also goes back in quietly and easily. This feature gives some access to the colony without having to disturb it, or it provides significant space for queen storage.

Was this a commercial?

The most useful general feature this unit provides is an extra clever working space in an otherwise chock-a-block full structure – a common beehive. There is essentially no space in a hive for a queen cage or even a pollen patty. This box helps with that issue. Also know that this equipment primarily helps beekeepers with a few colonies. It probably would not be practical for more commercially minded beekeepers with greater numbers of hives.

Nothing is perfect. The plastic feeder is smallish and requires frequent filling, and as can be seen in the photo, bees propolize all cracks and crevices. I don’t know how this gluing behavior will affect the operation of the unit in years to come.

Please know that I only have one of these Royalty boxes, and I like that one. That’s all I’m saying. You should form your own opinion. My comments here are like me telling you that I like my Ford F150 pickup. I’m not a truck salesman and – no – this was not a commercial.

Odds and Ends

Pete F. was emphatic. He saves all burr combs and wax scrapings. He then melts this and other wax. He adds an additional coating to his foundation inserts. He feels that this extra wax makes his bees a bit more eager to work with the insert and to construct combs. I suspect that he is correct. There is really not much wax on the plastic inserts that we are now using.

Thanks for reading this piece. For those who have written and I’ve not responded, please know that I try to get to all of you. Thanks for the comments. I read every one – even if I can’t always respond.

1Winston, Mark L. 1987. The Biology of the Honey Bee. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. Winston lists the tasks as: Cell cleaning, capping brood, tending brood, attending queen, receiving nectar, cleaning debris, packing pollen, comb building, Ventilating, guarding, first foraging

2http://www.royaltyhives.com/crown-work-box/

Dr. James E. Tew, State Specialist, Beekeeping, The Alabama Cooperative Extension System, Auburn University; Emeritus Faculty, The Ohio State University. Tewbee2@gmail.com; http://www.onetew.com; One Tew Bee RSS Feed (www.onetew.com/feed/); http://www.facebook.com/tewbee2; @onetewbee Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/user/onetewbee/videos