Extracting honey from cantankerous combs.

Odds and Ends – Dark socks and crystallized honey.

By: James E. Tew

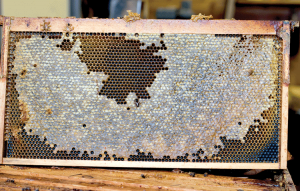

Extracting from cold, older combs

I am so, so sorry I started this topic. Last month I boldly said that I would finish my comments on late season (or out of season) honeycomb extraction this month. That was just a bit optimistic on my part. However, I have made progress.

In the last BC issue, I gave you my reasons for neglecting my bees and for missing my extracting window last year. I accumulated an unextracted honey crop that was one to three years old. This was more honey than my bees could ever use and increasingly, it was heavy and in the way of routine management procedures. My choices were to discard full honeycombs or extract them. Well, any beekeeper would extract these old, propolis-embedded combs rather than toss them – right? That was my decision, too. (Spoiler Alert – tossing these old combs now seems to be a much more appealing option.)

What follows in a normal aspect of honey extraction

Extracting honey is always a messy task – sweet, sticky, and messy. Bees, if at all possible, are always eager to help with the process. That assistance causes all kinds of confusion so honey extracting is done inside. I’ve extracted honey many times before. I know what to expect, but my expectations for processing old heavy honey were low. This is one of those beekeeping tasks that no one often discusses (akin to cleaning Winter “dead outs.”). True. It is satisfying to maintain the equipment and get it back into operation, but it is assuredly sticky work.

Some discussion points on honey extracting at any time

(In no order of priority)

(Especially applies to thick honey in heavy combs)

- Wear smooth-soled shoes. Running shoes or hiking shoes have classic traction treads. These treads become jammed with wet wax and propolis. Always an enjoyable task, these globs will need to be pried from shoe soles with knives or some other pointy object. Truthfully, I frequently take a short hike outside and scuff my shoe soles on the grass. Obviously, I am not extracting in my home.

- Put something down to protect the floor. Since I was expecting a heavy-duty mess, I used a blue plastic drop cloth. Many times, beekeepers use newsprint. Use whatever you want. Nothing works perfectly. Drop wet wax or propolis on anything – even the floor – and a tracking mess results. Expect the protective floor covering to stick to your shoes. “Anytime I drop something, I will pick it up.” No you won’t. You will be careful and neat for a while, but you will wear out. The droppings will start slowly and grow to a full-blown mess. What to do about this process? (That’s why we are working on this list.)

- In the extracting area, hot and cold water are nearly a necessity – at the very least, have cold water. While dealing with these troublesome combs, I rinsed my hands constantly. Wiping hands dry on your jeans is acceptable. You can only wear them once before washing – so use them as a towel. Otherwise, you will use rolls of paper towels. Yes, wearing a long apron helps. By washing hands frequently and scuffing my smooth shoe soles, I limit the “stickiness spread” as much as possible. This is as good a time as any to say that I hope there is a pressure washer somewhere in your life. Though this machine will give you a full-body wetting, it does a good job of cleaning floors and extracting equipment.

- Excess propolis is a challenge. In the case of combs that are a year+ old, propolis will likely have been extensively used to encase end bar lugs, edges – everything. Clearly, it will be difficult to remove frames; and when you do get these frames out, propolis chunks will drop everywhere. (Remember #2 above.) “Well, I will just scrape the propolis from the hive box before I extract.” Go for it. The box is crazy heavy. As you scrape and cut, propolis chunks are going to scatter everywhere and this tiresome process is going to take even longer. I used a heat gun to soften the bee glue, and I broke off any parts that were breakable. After I extracted the frames, I scraped them clean. The box and the frames will be much lighter. I also often ran my shop vacuum. It helped, but it’s just one more thing to do. (Now your shop vac is sticky, too.)

- Dead bees on (and in) the combs are a feature of this situation. Yep. Dead bees make this task just a bit even less pleasant. Some of the honey I extracted was from dead colonies that did not use it. I mean full deep frames. “Well, I would just give that back to bees and let them use it.” I have done that for several years. Over time, I have accumulated older honey that the bees have never used. I’m sick of moving it. Plus it makes Varroa treatments more difficult. Of course, all honey must be filtered. Dead bees in raw honey are not uncommon, but let’s keep that to ourselves.

That’s enough listing – it could go on and on

My theme in this piece is a discussion of extracting difficult frames – not the much easier extracting of nice white full combs. In many instances, there is overlap between extracting normal honey frames and extracting these older, more demanding frames. The list above presents some of that overlap between new honeycombs and much older honeycombs.

It was cold when I brought it in

The honey was cold (maybe 35°F) when I brought it in. This was all discussed last month. In preparation for extracting, I knew that simply warming it up to room temperature would be too good to be true. It was. At 70°F, the cappings were miserable to uncap. Even using a fire-hot uncapping knife, I had to hack and saw to get the cappings off. It appeared that this would take all Summer. It still may yet. I knew I needed heat – lots of heat.

Do not try this at home – indeed, you probably should not try it anywhere

I’m actually more than somewhat serious. I have snowmelt pads that are obviously used to keep Winter pathways open during snow season. Last Winter, I was surprised to learn that they were operating even when the temperature was well above freezing. I thought that they would thermostatically shut down when the temperature was above freezing. They were really warm. Hmmmm – what if . . . ?

If you try something like this, please, please do not start a fire or electrocute yourself. I don’t know how you could do either, but please do not try to discover a way. If you try using these devices for comb warming, know this: the manufacturer would not call or email me back when I described what I was planning to do. Clearly, they do not endorse it. Secondly, I have only used these mats a single time and I sat with the apparatus the entire time that it was hot. Why – because, I did not want to start a fire or electrocute myself. I am not recommending using such heating mats as a general procedure.

In fact, why have extractor manufacturers not already addressed this shortage. Any beekeeper with only modest experience knows that liquid honey flows better if slightly warmed. The regulated heating component should be thermostatically controlled and integrally paired with the extractor. All of you engineeringly experienced beekeepers, here is your chance.

The heated pads worked (mostly)

The pads worked – slowly – but they worked. It took about 40 minutes for the holding tank pad (pictured on the right) to warm the frames and honey to about 90°F+. I had the uncapping knife hot, and did the uncapping work with cappings and warm honey dripping all around me. These drippy frames went straight to the heated extractor. The supplemental heat made the combs considerably easier to uncap.

Not a fancy operation

I’m in a strange place in my beekeeping procedures and in my beekeeping life. While working for Ohio State, I had beautiful and complete extracting setups – from small to large. Now, I am a small producer with old or aging extracting equipment. Yes, I have downsized. In fact, the extractor that I have pictured on the right is a vintage A.I. Root 4-frame variable speed extractor. The hand-cranked extractor is one from Kelley that I am currently using for a heated tank. The extracting equipment worked okay – just okay. Lots of wobble upon starting the extractor, but this would happen with any extractor start up. Having a motorized extractor is nearly a necessity.

Several years ago, I used the small garden tractor referred to in the first article to pull the trailer into my shop. There I attached an extractor to the trailer bed. In the setup used here – there is no tractor. In the older setup, the tractor firmly held the lightweight trailer in place. But without the tractor ballast, the trailer/extractor was a bit bouncy. My idea was that the trailer springs would absorb some (ideally most) of the extractor vibrations. Without the tractor as an anchor, the trailer worked okay, but not well.

Ratchet hook binding with the nut on each side of the extractor. This upper attachment prevented the basket from striking the hook inside the extractor.

I cobbled up a quick system for attaching the extractor to the trailer. Two heavy ratchet straps around the trailer bed and two smaller ratchet straps attached to the top of the extractor and on the bottom end, attached to the lower, larger ratchet straps. You see all of this improvisation had to be quick, because I boldly told all of you that I would have this done this month. I was more than a bit optimistic.

Observations on the extracting process

Honey extracting is a typical beekeeping process – regardless of the comb age. The extracted frames always come from the extractor in wet condition. When extracting low moisture honey, the honey tends to sling out in heavy droplets that cling to the side of the extractor wall. The heat pad on the extractor greatly helped the thick honey move down the side of the extractor. But it took time. Extracting thick honey from old combs takes more time, and more honey is left in the extracted combs.

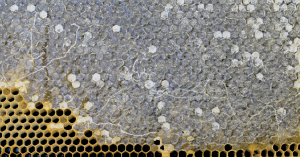

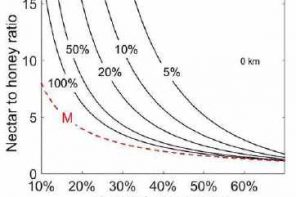

Another issue is that older honeycombs contain a significant amount of granulated honey. Initially, I hoped that the added heat, given ample time, would liquefy some of the sugared honey. It may have, but not very much. Beeswax melts at 149°F. That number could be as low as 143°F depending on other factors. The wax is soft at 100°F. Ironically 104°F is a common heat level for liquefying honey. It would be tricky to deal with sugared honey using my crude heat systems. It will be easier to address crystallization issues after the honey has been extracted.

Another oddity

At a recent meeting, the bee louse (Braula caeca) was a brief topic. There was mostly agreement that Varroa control chemicals had also killed the bee louse1. Well, in older honey in my apiary, the bee louse is alive and well. I wonder if the undisturbed honeycombs allowed more development time. I don’t have a good answer. Actually, I don’t have any answer at all.

Great odor – that helped a bit

One of the few enjoyable aspects of this task was the delectable smell that filled the air in the shop. Once all the heating was underway and all three devices were hot, the shop smelled as though I was the best cook in the state. At least this job does not small bad like the putridness of cleaning dead colonies.

Summary

If at all possible, extract nice white combs as soon as possible. Processing thicker honey in stronger combs having abundant propolis, will require supplemental heat to uncap and to extract. Contain the stickiness as much as possible and have a plan for the clean up. I wish you would not set the wet supers outside, “for the bees to clean up.” That always turns into a wild situation.

Now my obligation to you is over. I want to finish this work and get this contraption out of my shop. Have any of you developed a practical method for securing your extractor – to something (pallet, trailer, bolted to cement floor, what?)?

Odds and Ends

A good friend wrote me describing a procedure he used to liquefy his honey when it crystalizes. Now, mind you, this man is not a beekeeper, but is a consistent honey consumer. He lives in southern Alabama where the weather is nearly always warm/hot.

His method is to use two black socks to encase the honey jar. Loosen the cap a bit. Set the arrangement in the hot sun. Monitor and stir occasionally. Liquid honey can be derived from the sun and dark socks. For flavor’s sake, don’t overheat. This is a new process for me.

Other hot climate beekeepers told me that that when re-liquefying cases of honey, they loosen lids and simply put it in the trunk of their car. Close the lid and go about their business. Okay. I can see how this would work. There would not be much control on the amount of heat, but the heat would be free.

Good times

Hey, Wyoming Bee School and Palm Beach County Beekeepers, thanks for a great time. My wife and I learned a lot, saw a lot, and came home pleasantly tired. Both were nicely organize meetings in interesting areas. Good memories.

Thanks for reading

Thanks for reading. When this extracting project is finished, I want to continue to revamp my apiary. I have invited some virtual visitors to my apiary in May and now I must clean up for the event. There’s never a slack moment in the beekeeper’s world.

1The bee louse is an apparently inconsequential colony resident. It is a wingless fly. The larval stages of this fly tunnels beneath honey cappings. Presently, it is thought that other than this cosmetic damage, no other harm is done.