By: Ryan McDearmont

With their striking coloration and intricate hive aesthetics, it’s no wonder that honey bees have become a favorite subject of filmmakers across the world.

The unmistakable iconography of the bee has been utilized time and time again in no shortage of movies, often for differing effect. The 1973 Spanish drama film The Spirit of the Beehive uses bees as symbolism for an organized ideology, whereas the 2007 comedy Bee Movie structures no end of puns and visual gags based on audience conceptions and stereotypes of the honey bee. Although documentary programs and films such as More than Honey (2012) and Vanishing of the Bees (2009) provide a more fact-based approach to the world of bees and beekeeping, it’s important to note that movie audiences across the world are likely most familiar with apiculture through the fictional films which both appreciate and demonize the common bee.

As such, it’s important to look at notable bee-featuring movies throughout the years – not only to understand how bees are used and featured in film narrative, but to get a sense of how these titles affect those outside the world of beekeeping. What, if anything, do these pieces of media have to say about bees? Are bees represented in a positive or negative light, and what assumptions does this representation form in the mind of an audience? While an unassuming viewer might walk out of the aforementioned Vanishing of the Bees more attuned to the grave reality of colony collapse disorder, what thoughts will they take with them from a movie titled Killer Bees (1974), or perhaps The Savage Bees (1976)?

Although these luridly-titled “natural horror” titles have largely fallen out of favor (cheap goofs such as Sharknado aside), it’s undeniable that such movies were once Hollywood’s primary vehicle for the world of apiculture. From 1966 to 1978 alone, there were no less than six major films featuring bees as the sole, ticket-selling terror. These bee exploitation films, or “beesploitation,” for simplicity’s sake, place the humble honey bees as unavoidable, world-ending boogeymen sprung from mother nature.

Whether altered by the hand of a mad scientist or a cosmic fluke, the amped-up Apis of common beesploitation films prey on regular moviegoers’ unfamiliarity with the truth of bees. In these movies, deadly stings are a way of life when killer bees reign judge, jury, and passionless executioner over mankind. The yellow and black drones belong to a hive, an “otherness” that no human can hope to understand, and thus, the heinous insects must be destroyed.

This appropriation of the more complex and “fearful” aspect of honey bees is the crux of most beesploitation films: the terror of being hurt, even by a sting, and the terror of a “hivemind” outside of our control make bees easy bumps in the night for those not familiar with the truths of beekeeping. To understand this general fear, it’s best to examine two different beesploitation films from two parts of the world.

First, the cheesy 1966 British “horror-thriller” film The Deadly Bees, arguably the first ever proper installment in the beesploitation “genre.” Second, 1978’s The Swarm, a massive, terrible Warner Bros. production that’s perhaps the biggest and most infamous of all bee-centered horror films. By diving into these two ridiculous titles, we can start to understand why bees are still so feared to this day . . . and maybe laugh a bit at some B movies, too.

First, the cheesy 1966 British “horror-thriller” film The Deadly Bees, arguably the first ever proper installment in the beesploitation “genre.” Second, 1978’s The Swarm, a massive, terrible Warner Bros. production that’s perhaps the biggest and most infamous of all bee-centered horror films. By diving into these two ridiculous titles, we can start to understand why bees are still so feared to this day . . . and maybe laugh a bit at some B movies, too.

A loose adaptation of H.F. Heard’s 1941 mystery novel A Taste for Honey, The Deadly Bees originally featured a script by Psycho (1959) author Robert Bloch. With writing by a certified thriller veteran, and plans to star horror powerhouses Christopher Lee and Boris Karloff as competing beekeepers, The Deadly Bees looked ready to deliver. However, Lee and Karloff were unavailable, and Bloch’s script received last-minute “improvements” from the film’s director, Freddie Francis. What resulted, then, was not a tense white-knuckler in the vein of Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963), but rather, a cheap, stiff, and unintentionally humorous potboiler with a lot of plastic bees glued on faces.

The plot leading to the reveal of these shoddy pollinator props is fairly simple: exhausted by the popstar lifestyle, singer Vicki Robbins is sent to recuperate at a bed and breakfast on the remote “Seagull Island.” Two rival beekeepers, Mr. Hargrove and Mr. Manfred, call the isle home, and it’s clear they hide more than a few secrets. Vicki quickly uncovers a plot involving genetically altered killer bees, and the other characters fall victim to deadly swarms – one of the beekeepers is responsible, but which?

Featuring shaky acting, ‘60s hairstyles (look out for the beehive!), and a man who keeps an apiary in the walls of his home, The Deadly Bees is weird, silly, and immediately dated. Lines such as “I was able to hypnotize the deadly killer bees!” aren’t revelations, but punchlines. By the time Vicki is thrashing in her bed, experiencing buzzing, bee-based nightmares, it’s hard not to have let a few chuckles loose. In fact, The Deadly Bees is so ripe for joking jabs that it was featured on the ninth season of movie mocking program Mystery Science Theater 3000.

Despite these moments that make for easy teasing, however, it’s clear to see why The Deadly Bees might put viewers off honey for a while. When Hargrove’s wife is inevitably set upon by the eponymous killers, the film shows actual footage of bee stings, even depicting the tearing of the stinger as the bees pull away. By using this graphic visual display to magnify the pain of a bee sting in audiences’ minds, it’s not surprising as to why the average viewer might duck away from a harmless honey bee upon leaving the theater.

This trepidation surely isn’t helped by the film’s general depiction of beekeeping, which presents the practice as esoteric, and beyond the protagonist’s comprehension. “It’s dangerous to involve yourself in matters you don’t understand,” says Mr. Hargrove once Vicki dives into the island’s mysterious apicultural world. Bees are kept in squalid, foreboding spaces, or (literally) behind closed doors. When we see intercut footage of a professional handling a hive, the camera moves in close on their methodical movements, and the music strikes a sinister sting.

The Deadly Bees frames the routine of beekeeping as evil; a simple interaction likened to a killer sharpening their knife. It’s through this manner of presentation that apiculture is demonized in the average beesploitation movie. With a touch of horror-film flavor, the common actions of beekeeping are made menacing in the eyes of audience members; a dread only magnified by lack of understanding. With the mundane truth obscured behind filmmaking flair, little sympathy remains for beekeepers.

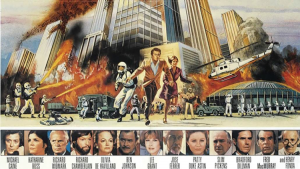

At least The Deadly Bees keeps apiculture more or less grounded in reality – the same can’t be said for The Swarm; an absurd, bombastic Hollywood film which effectively killed the beesploitation boom that The Deadly Bees began. The Swarm, featuring Michael Caine between critical hits A Bridge Too Far (1977) and Educating Rita (1983), posits bees as weapons of mass destruction; a natural force so far outside of human control that the only method of taming is through bombs, chemicals, and scorched earth warfare.

Again, the story is easy: mutant Africanized killer bees with stings deadlier than jellyfish make landfall in the United States, decimating a Texas military base in the process. As the ravaging insects raze their way towards Houston, Michael Caine’s entomologist character must work with the government to neutralize the bees before it’s too late. This, of course, is an excuse for scenes of death, destruction, and decimation, all apparently at the hands (or claws) of the honey bees. Featuring between 15 and 22 million bees handled by 100 people, The Swarm went all-in on its depiction of an apicultural apocalypse.

The excesses of The Swarm make The Deadly Bees seem like a genteel drama in comparison. Endless slow-motion death-by-bee scenes accompany train crashes, mass fires, and a segment in which the bees cause a power plant to explode and wipe out an entire town of over 36,000 people. It’s a classic American disaster movie in the truest sense: an unforgettable, over-the-top production with a huge budget, but a silly concept and unintentionally funny script. The film’s penultimate sequence sees the military fighting off bees with flamethrowers when the swarm descends upon Houston – as buildings burn, General Slater (Richard Widmark) observes in dismay and remarks: “Houston on fire . . . will history blame me, or the bees?”

The grave performances, rendered humorous in hindsight, don’t do much legwork in framing honey bees as a credible threat. No, that job is done by playing upon the real-life paranoia surrounding the expansion of the Africanized bee. Likely already feared by audiences at the time, The Swarm exacerbates such terror and misunderstanding by presenting the species as stone-cold killers, years before they made landfall in Texas. It’s because of misrepresentation such as The Swarm that fear of the Africanized bee, and by extension, bees as whole, thrived and continues to proliferate to this day.

However, the bee itself isn’t the only fear lurking in The Swarm. Beneath the chitin lies the same insular, us-versus-them terror found throughout American science-fiction monster movies dating back to the 1950s. Preying on Cold War fears of (literal) foreign elements and the horror of an enemy lurking at home, The Swarm takes aim at lingering dread of a nuclear arms race. The military base ravaged by the bees is a ICBM launch site, a neutralization which Gen. Slater remarks has never been accomplished by enemy spies. Once the bees have annihilated the small town of Marysville, it’s mentioned that perhaps this “invasion has been here sometime . . . breeding; increasing.” In The Swarm, once benign ally shows its true colors as a sinister, alien force, and for failing to curtail it, America pays the price.

However, the bee itself isn’t the only fear lurking in The Swarm. Beneath the chitin lies the same insular, us-versus-them terror found throughout American science-fiction monster movies dating back to the 1950s. Preying on Cold War fears of (literal) foreign elements and the horror of an enemy lurking at home, The Swarm takes aim at lingering dread of a nuclear arms race. The military base ravaged by the bees is a ICBM launch site, a neutralization which Gen. Slater remarks has never been accomplished by enemy spies. Once the bees have annihilated the small town of Marysville, it’s mentioned that perhaps this “invasion has been here sometime . . . breeding; increasing.” In The Swarm, once benign ally shows its true colors as a sinister, alien force, and for failing to curtail it, America pays the price.

Political insinuations aside, The Swarm ultimately fails at being scary, at least by today’s standards. The cheesy script, poor performances, and hilariously over-the-top disaster sequences are hampered even further by a bloated two hour and 36 minutes “restored” runtime, which film fans might recognize as being three minutes longer than Coppola’s Vietnam epic, Apocalypse Now (1979). It makes sense, then, that The Swarm barely scraped together $7.6 million box office on an $11.5-22 million budget, currently touts a 13% (out of 100%) on review aggregate Rotten Tomatoes, and was called “the worst film ever made” by The Sunday Times. Despite this failure, there are rumors the American Bee Association acted against The Swarm for “defaming the American honey bee,” but no one knows if a lawsuit was ever filed.

In the end, it likely wouldn’t have made a difference. Even though the end credits of The Swarm feature a disclaimer that the “killer” bees featured in the film bear no resemblance to real, crop-pollinating honey bees, the damage is done. If movies such as The Deadly Bees and The Swarm do their jobs, audiences leave the theater terrified of bees, petrified that every innocent, bumbling bee will attack on sight. Existing anxieties about insects are cemented, and common misunderstandings about honey bees become concrete convictions. It’s a deadly sort of presentation that, for bees at least, has thankfully phased out of public demand in recent years.

Compelling documentaries have since replaced sensationalist shockers as the primary mode of representation for apiculture in the media. Apocalyptic aesthetics give way to appreciation for the natural beauty of the bee, and tales of terror subside into engaging education. Bees have come a long way in the media since the salad days of beesploitation and the legend of killer swarms, but the effects of such movies still resonate to this day. When someone ducks away from a lone honey bee, or shudders at the concept of keeping hives, it’s the breed of misinformation perpetuated by The Deadly Bees and The Swarm that fuels the fire. These movies are in the past, but unfortunately, the struggle for truthful representation is not. When we get that truth, however, it’ll taste sweet as honey.