Elizabeth Eliza Douglas

Elizabeth Eliza Douglas

Nina Bagley

Elizabeth “Lizzie” Eliza Douglas was born in Gorham Cumberland, Maine, in September 1844. Lizzie’s father, Freedom Douglas, and mother, Elizabeth Ann Knight Douglas, had nine children. Records show that Douglas’s relatives arrived in Gorham Cumberland, Maine sometime around 1790. Gorham Cumberland village during the 1800s consisted of several inns, blacksmiths, tanneries and shops. The local school was a one-room brick schoolhouse. The first train depot was built in 1850, connecting the rest of New England. I’m not sure how Lizzie met her husband Charles B. Cotton. They were married in 1862 in Portland, Maine. She was seventeen. Mr. Cotton was twenty-five years old. The 1800s census shows Charles B. Cotton’s occupations as a teacher, agriculture and farmer; he could read and write. Charles’s grandfather was the first tanner in Gorham. Records also showed his uncle John Cotton was accused of being insane because of his peculiar religious outbreaks during church services calling the pastor a liar.

Lizzie Cotton had eight children from 1863 to 1881. My curiosity about Lizzie started when I found her online book, The Controllable Bee Hive, in the University of Maine’s Library. (The Controllable Bee Hive and New System of Bee Management, 1887, Annual Circular, Lizzie E. Cotton. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu) As I was reading the book, which was a quick read, the information was interesting.

Chapters include: Swarming Controlled, Bees Wintered Safely, No Loss From The Bee Moth, Honey in Glass Boxes, Movable Comb Frames and No Stings. She was assertive and adamant about using her bee plan. She came across as very confident! She advertised her book and a controllable bee hive in the bee journals. Lizzie would make the sale but not ship the goods. Worst of all, the bee folk hardly received a refund! The swindled bee folk had no problem writing to Gleanings in Bee Culture, American Bee Journal and Prairie Farmer that Lizzie Cotton was a fraud! She was accused of honey adulteration, being a swindler and a fraud of the male gender. (“Naughty Lizzie Cotton.”)

My question was how could a homemaker have the time to write two books and swindle bee folk? Wives in the 1800’s typically gave birth about every other year from marriage until their childbearing ability ended. I wonder if it was her husband’s idea to write Controllable Bee Hive and use his wife to sell the book? Perhaps Charles B. Cotton inherited the sickness his uncle John Cotton had? I know he married Lizzie in 1862, so he was home and not fighting in the Civil War.

I couldn’t find any records of Charles serving in the Civil War. I’m speculating that some health issue might have prevented him from serving. I’m giving Lizzie Cotton the benefit of the doubt that she obeyed her husband and didn’t question him about business. I’m unsure what Lizzie’s education was; I couldn’t find much. I did find in the 1870s census she’s listed as a housewife and can read and write. I can only collect facts and go with my feelings and research in telling Lizzie Cottons’ story.

Lizzie wrote two books: in 1880, Beekeeping for Profit, and in 1883 The Controllable Bee Hive.

A. I. Root, Gleanings 1881: “The Controllable bee hive book was well done. The only fault was that the book cost a dollar and was only 128 pages and thin, whereas you could get other books with more pages for 50 cents. I know that not everybody agrees with me in pricing books according to size, but for Mrs. Cottons’ good and the book’s sales may increase. I would suggest that it be sold cheaper or added more to it.

People are in the habit of getting a pretty good-sized book for a dollar, and I feel they will be disappointed, I believe: Mrs. Cotton is an earnest, hard-working woman, and I wish to see her succeed. I’m willing to sell her book if she permits me. I’m satisfied that she has seen her mistakes and is ready to correct them.”

Lizzie Cotton’s recipe for Feed: according to A. I. Root, feeding the bees using her recipe, she claimed she got 350 pounds of honey from one bee hive, which she sold for 35 cents a pound using her so-called controllable hive, which A. I. Root said was similar to Jasper Hazen and Mr. Quinby’s controllable hives. Lizzie Cotton was being accused of honey adulteration, because she fed her bees sugar water.

Lizzie Cottons’ recipe that she sold for $10.00: “Two, eight pounds of coffee, crushed sugar, add two quarts of soft water, and whites of two eggs: bring to the boiling point over a stove fire, being very careful not to burn it. Skim off carefully all scum or sediment that rises so that the feed, when cool, will be clear, about the consistency of the new honey.”

Mr. A. I. Root: “I confess it is a little hard to see how one is trying to do right should charge $10.00 for such a recipe but at the same time, I do not know, but it is the best recipe I have ever found. You know how I have talked about selling recipes in these years past. Although this is an excellent bee-feed, whether you use the eggs to clarify it or not, I should hardly like to endorse the following, which we find in Mrs. C’s book.”

Lizzie Cotton was the most scorned woman beekeeper during the 1800s. It’s not sure how long she kept bees. In her book, she claims thirty years. Or was it Mr. Cotton who kept the bees and wrote the book? That would make more sense to me. After all, he was a teacher at one time.

American Bee Journal 1882: “Lizzie E. Cotton! Ah, Lizzie! You cruel siren that wishes to advertise her remarkable “New System” of Beekeeping in the Farmer. Well, Lizzie, you can’t do it. The bee folks say you are a fraud. Lizzie, they go so far as to say you are a confident man. She advertises a hive that is useless crap. When sent money, she usually sends nothing in return. Her “book” only exists in advertisement or imagination. Mr. A. I. Root sent her a dollar for the same book years ago and has her letter of acknowledgment, and a later one promising the book as soon as published, yet the book fails to appear.”

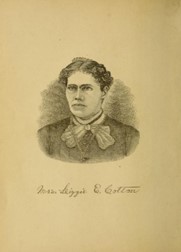

American Bee Journal 1882: “A beekeeper in this neighborhood called on the lady soon after her purchase. She ascertained that the queen was worthless and advised her to send immediately for another queen, which Mrs. Cotton promised should be shipped about the 25th of July, but it has not made its appearance. Now that the bees have died, the poor woman has nothing left for her $23.52 but one “controllable beehive” and Mrs. C’s famous book on bee culture, with her photograph on the first flyleaf. What a boon!” (The lady referred to is Miss Lovina Ewing, West Berkshire, VT.)

The Western Rural says: “Lizzie Cotton is advertising his bee knowledge in some agricultural papers. Lizzie is a fraud of the male gender and newspaper office that does not know it holds a great deal of stupidity.”

An advertisement about practical beekeeping by Lizzie Cotton appeared in Farm and Fireside Springfield, Ohio, 1879. Mr. A. I. Root read it. He contacted the newspaper, stating, “Mrs. Cotton has the disagreeable habit of making no return for money sent her, though she often makes fair promises.”

Mr. A. I. Root advised the newspaper “that Lizzie Cotton had a habit of not paying her bills, and the newspapers should shun her.” Mr. A. I. Root trusted Mrs. Cotton because she was a woman. After all, she represented herself as a woman and would write so handsomely and feminine when sending her advertisements to the newspapers: but her handwriting looked masculine when it came time to pay the bills.” It gets conflicting to me! Did Mr. Cotton persuade her to write to the newspapers? We need to remember women had no rights during the 1800s. They were considered helpmates, so perhaps she kept silent because the repercussions could be worse for her and the children. The temperance movement was going on in the 1800s. Maybe Charles Cotton drank; who knows. It appears from A. I. Root’s accounts the masculine handwriting probably was Mr. Cotton.

February Gleanings 1881, A. I. Root: “An excellent picture of Mrs. Cotton given as the frontispiece of the book; and if one takes a good look at the face of the author (which by the way is by no means an unprepossessing one), it is with a feeling of sadness that the bee folk spent so much energy at least in part, in a mistaken direction.”

The bee folk were very harsh and judgmental towards Lizzie Cotton. A few of Mrs. Cottons’ friends came to her defense, but that doesn’t mean they weren’t aware of what was happening. Mrs. Cotton had me perplexed and convinced that Mr. Cotton might be behind the swindling. I put myself in her shoes. It wasn’t uncommon for women to marry men they weren’t in love with, and arranged marriages were ordinary. Women were to take care of the home, cook, clean, have children and obey their husbands. In 1886, Mrs. Cotton’s daughter Carrie died from a tumor, and her parents died the same year. The heartbreak and grief she must have felt. How could one focus on the business of bees?

Thinking I finished Lizzie Cotton’s story, I came across this article for the American Bee Journal: Mrs. Cotton’s Transactions by A. P Fletcher.

Mr. Fletcher wrote an article in the American Bee Journal on Lizzie Cotton’s frauds. He remained in the northern part of the state for the Winter and did not have the American Bee Journal so he couldn’t read the responses to his article on Lizzie Cotton’s actions until he returned home. “Regarding Mr. R. E. Holmes offer to pay $5 to you or anyone who will furnish proof of Mrs. Cotton’s swindling, I would like to know what he means. Have not you, and has he not ample evidence from many sources, that she practices swindling right along?” He continues to say his friend sent for the “so-called sample controllable hive. It was a roughly made basswood thing only six inches deep and six by 10 inches inside. What is this but fraud? I can cite several.” He says that A. I. Root can furnish ample proof, and the lady in Berkshire received returns for her $20 refund in the sum of a hive and handful of bees on five frames. “Mr. Holmes needs to take my word for it. Hundreds of others have received the same doubt. I think Mr. Holmes ought not to uphold Mrs. Cotton’s fraudulent transactions in the eyes of so many of her defrauded customers all over the land.” So it looks like A. P. Fletcher was calling Mr. Holmes out. “For conscience’s sake, how many more instances does he ask you to prove before he is ready to come down with his $5?” Now Mr. Holmes pretended to know all about Mrs. Cotton. When asked about her, Mr. Fletcher found that Mr. Holmes had never seen her or even been at her place.

“Mr. Holmes said she did not send me that little beehive to swindle me, but she did it because she did not know any better; that she was as ignorant as a “horse-block” and that the “old man” had been through bankruptcy and didn’t amount to anything.”

After reading the article Mr. Fletcher wrote, I felt he answered some of the questions I had about Mrs. Cotton. Maybe she was as dumb as horse block, and perhaps she wasn’t. Maybe Mr. Fletcher was right; Lizzie Cotton swindled right along. I would hate to think that’s the case.

Lizzie Cotton in 1910, at age 64, was living in West Brook City Ward 1, 4, 5, Cumberland, Maine. She ran a boarding house for the last twenty years of her life in Westbrook while her husband lived at the family farm in Gorham; it appears they were separated. Lizzie Cotton had eight boarders, including her three sons. Charles Cotton died in an asylum in Portland, Maine in 1915 from senility.

I’m going with my intuition on this; after all, Mrs. Cotton did say her husband didn’t amount to much, so maybe the right hand didn’t know what the left hand was doing, or perhaps it did! Mrs. Cotton died in 1917 from kidney complications. I’m guessing she had Bright’s disease, which could be why her eyes looked dark and sunken. I’m going to say when she said she was ignorant as a horse block, it’s because she married Charles B. Cotton.

Nina M. Bagley

Columbus, Ohio