Part 1: It Has Always Been

James E. Tew

English is my only language.

I have always envied those of you who are multi-linguistic and acquired multiple languages as a child. Not me. As a graduate student, I sweated through Introductory German and Spanish and learned just enough to meet my required language obligations – and not a single palabra more. Those of you who learned other languages – painlessly – as children were fortunate.

I accidentally learned computer use

My wife typed my required academic papers on a Smith-Corona portable typewriter. Hardly ten years later, she was teaching high school students to use Tandy Radio Shack computers with primitive TRS-80 Scriptsit1 software. She taught herself the mechanics of computer use. My career-long job at Ohio State required me to learn various computer functions and to regularly use them. I never had a plan to grow in my computer literacy, it just happened as I met my routine job requirements. Now, while I am no electronic whiz, for my age, I am a reasonably proficient computer user. My wife and I were lucky. We learned slowly and we learned over a long time. It wasn’t painful. In fact, my computer has become one of my best electronic friends.

I stumbled into beekeeping

I never had a plan to become a beekeeper. My initial plan was that I would become an entomologist, but while pursuing that goal, I fell into beekeeping. I am a lifelong woodworker. When I was first exposed to beekeeping, one of my first thoughts was, “I can build all of this stuff.” For years, I did just that. Ironically, of the hundreds of boxes I built, none remain – not one. In the late ‘70s, beekeeping was simple and practical. I was lucky to have started when it was so much simpler. You really could build your own equipment, and you didn’t need a lot of money.

I admire today’s New Beekeeper

If I had to start beekeeping today, I don’t know that I would. It’s daunting. It’s expensive. If I had to begin learning computer use today, I don’t know that I would – or could. If I decided to become a woodworker today, I doubt that I would. I am certainly not going to seriously study other languages at my age.

So, I admire today’s new beekeeper. Modern beekeeping is complex – indeed, I would say that it is needlessly complex. While mite control and queen management equipment needs are complicated and necessary, a good number of the listings in bee supply catalogs are not truly required. These apicultural appliances are listed because I want them, but not because I must have to them to keep my colonies productive. Today’s catalogs are beautiful, full color publications filled with bee baubles that fire me off and make me want to spend money. But I confess, that at times, I must stop and study the catalog item to understand what a particular piece of equipment is used for and exactly why I want it.

In life, if you stop, it will pass you by. Beekeeping is no different. Beekeeping is in transition. It has always been in transition. The beekeeping I started in the early 1970s is not the beekeeping of today. Not better. Not worse. Just different.

We never used skeps in the US

Seeley, in his book, The Lives of Bees2, postulated that, when searching for nest cavities, swarming bees could have come to human homesites and found unused baskets and containers that the homeless swarm could claim as their nest abode. Of course, humans, desiring sweet honey, took notice of this hypothetical scenario and began to fashion baskets just for bees ergo – skeps. It was so much better to have the colonies right on the homesite rather than having to beeline them all over the surrounding environs.

In this country, especially on the eastern and southern sides, old growth forests were abundant – standing in the way of progress (as it were). US beekeepers rarely used skeps to house bees. Lumber was plentiful, so (apparently) we built boxes for our bees and called them box hives. A technical concept – right?

The hive design epoch was a glorious time in beekeeping development. Beekeeping has a complex history of tried and discarded bee hive designs. We have worked from the very earliest days of bee colony management up to this very moment trying to develop the absolute best “box” for our colonies. But to quote lyrics from the musical group – U2, I still haven’t found what I’m looking for.” With great gusto, modern-day beekeepers continue to design and redesign beehive styles. There’s no end in sight. Nothing wrong with that.

Beekeeping is in transition. It always has been evolving.

In my earliest beekeeping years, box hives were still occasionally used by older beekeepers. These crude hives were not coveted and, being difficult to inspect for diseases, were commonly considered illegal by state regulatory authorities. These crude boxes represented old-styled, unimproved beekeeping. Ironically, these simple box hives represent the last hive design that completely allowed the bees to lay out the interior combs in the style that they wanted. No frames and no foundation – box hives were the last natural bee hive. Beekeepers just supplied the cavity. The bees supplied the internal appliances.

One of the greatest lamentations of my bee life was that my brother and I did not document one of the last box hives apiaries in our home town before he and I converted all the irregular boxes to “modern” hives. So eager was I to make these hives better, I snapped not a single photo of the old rustic boxes as we transferred them to “modern” Langstroth hive designs.

There were USDA (1918) pamphlets describing how box hives were to be converted to Langstroth equipment. The old way was dying, and I was there for a bit of the departure and did not document the passing. This was a major transition through which beekeeping passed. You probably missed it.

Bee Lining, an old-time procedure that has transitioned into obsolesce.

Box hives are not the only beekeeping concept to pass into oblivion. There is an entire beelining technology that is now gone except for the few who still perform the procedures for enjoyment and natural satisfaction. Is bee lining now like modern-day Geocaching (https://www.geocaching.com/play)? Today, finding bees by lining them seems to be only kept alive by a dedicated few.

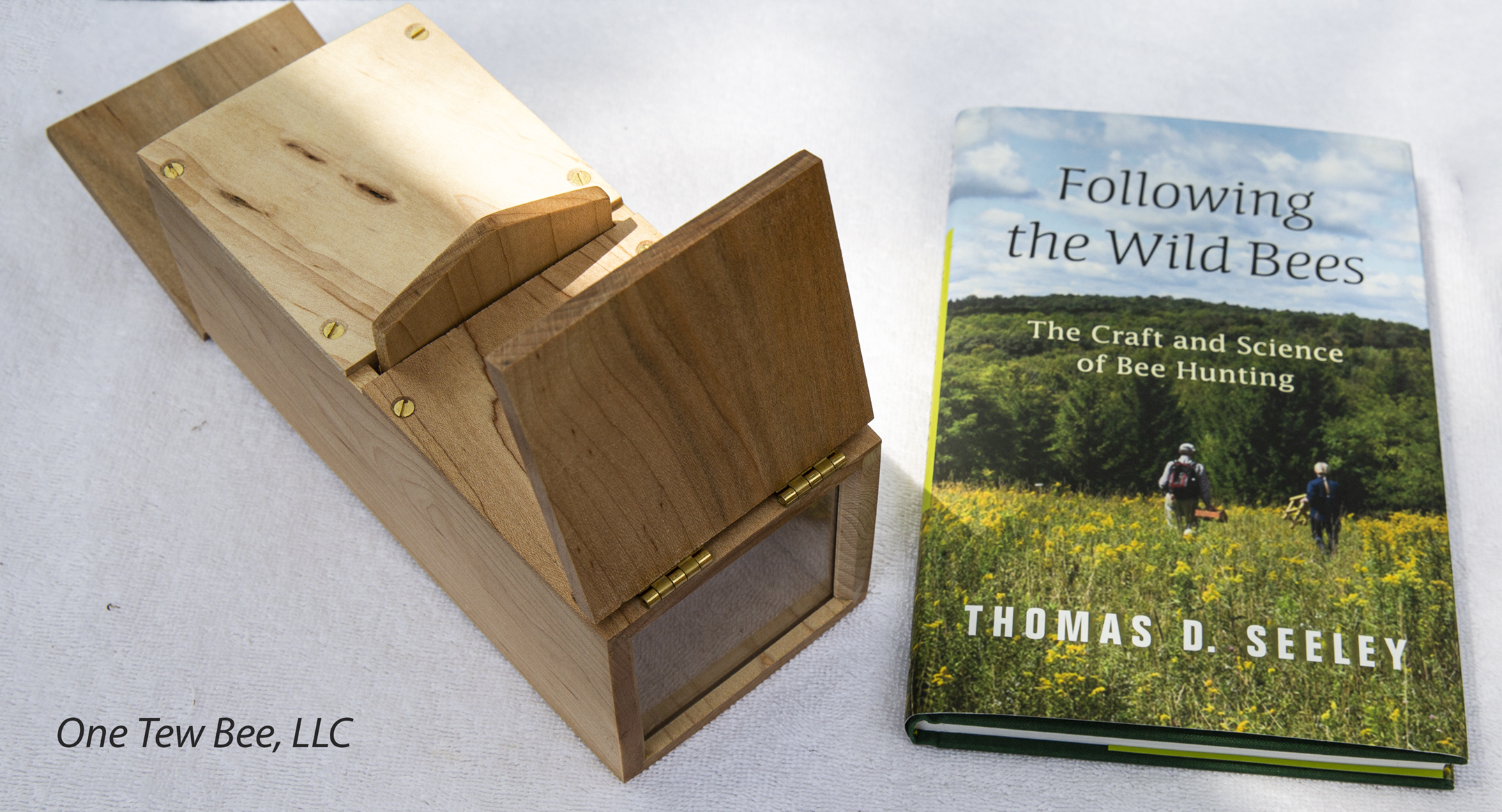

The technique required a small, improvised box4 to capture a few foragers at water or food sources. While confined within the lining box, bees were dusted with some kind of powder – maybe powdered sugar – and then, when individually released, their flight path was visually followed as the freed forager flew back toward her nest site. Of course, this process is not as easy as it sounds and took time and commitment and multiple dusted foragers. Success was never guaranteed. Recently, Seeley5 wrote a book on this subject and generated renewed interest in an old bee management procedure.

On this bee lining subject, I have been saving a story for more than a year that is an old, old memory recited by a beekeeper who lined bees as a child. I will not use his name here, but E.T., if you’re reading this, you know who you are, and you know it’s your story. I had thought that a proper moment would come along within an article for this memory, but due to the unique features of this story, an opportunity has not yet arisen. Happily, it fits well enough here. So, for the first time in print….a old time personal memory of beelining.

Children lining bees

It was a simple procedure. No lining box was used – just six kids of varying ages. Flour was sprinkled on several bees at a watering source or at a food source. As the disturbed forager took flight, a sharp-eyed kid would run after the marked bee until the bee was lost. The kid would then wait, at that spot, until another flour-marked bee flew by. Then run again. The kids worked in relays, dusting, running, yelling, and pointing. E.T. said that they wanted dusted bees to stay near ground. The flour dust made the bees heavier, thus keeping them nearer the ground and marking them as well. Bees flying higher, against the sky, were harder to see. If possible, dusting bees near an open field was preferable because bees would fly lower across an open field.

Using nothing more than a bit of flour, six kids, and a lot of energy, these kids would spend the afternoon – in game like fashion – chasing after white-dusted honey bees. After successes and failures, a nest site would frequently be found. These beelining events were happening from about 1946-1950.

The discovered nest was nearly always in a tree cavity – some nests openings were high while others were lower. During those times all those years ago, land boundaries were more of a suggestion than a restriction. In my own experiences from those times, a kid could just roam the world. It was yours. Don’t let a few fence rows hold you back. Once found, E.T.’s dad would contact the land owner for permission to get the tree, which was subsequently cut down and torn open. A tree was never taken without permission.

They did not always line the bees. Sometimes, the kids would just wander through swamps and forests looking and listening for wild colonies. Also, hunters would tell his dad about bee trees that they noticed. Bees were plentiful and common. No thought was given to their individual survival concerns.

Amazingly, while the nest was being destroyed, no typical protective gear was worn. E.T. did not even own bee gloves or veils. He said that the bees were crazy defensive at first but calmed down and began to engorge on honey6. Yes, they were all stung – multiple times. The bees were dark, small bees – probably some kind of German variety.

His Dad was not a beekeeper and essentially had no interest in becoming one. The most hives E.T.’s family ever had was a single box hive – just one. They had no concern for the bees. They never made any effort to save anything but honey. Bees, brood, and wax were simply discarded. In no way were these kids beekeepers. They were accomplished “honey hunters.” But that was not all they hunted.

In a way, E.T.’s family also lined turkeys. One of the kids would stealthily follow a turkey hen – but not too close. If the hen spooked, the kid would move from view into a nearby hiding spot. (JTew guess – the kids were probably following a partially domesticated turkey hen hiding a nest in the wild.) The kids would begin to formulate an idea where the hen was going. Over time, a trail would start to emerge. One of the kids would hide, out of sight, near the trail the hen turkey was taking. Different kids would be hiding in different places. The turkey hen was smart and would not take the same pathway and would abandon the trip if disturbed. The kids were pretty clever, too.

Once the nest was found, the kids would use a long-handled wooden spoon to rob some of the eggs – but not all. If all the eggs were taken, the turkey would abandon the nest. The nest could not be touched in any human way. The pilfered turkey eggs were put underneath a brooding chicken hen. During one specific summer, the kids successfully raised something like 20 turkeys from these eggs robbed from various turkey nests and incubated beneath chicken hens.

My friend, E.T., said that after he matured and became a committed beekeeper, he was pained at how much damage he and his siblings caused the bees. Disregarding the season, they took the honey any time they could find a nest. He said that they did not know to have concern for the condition in which they were leaving ravaged colony. For both bees and turkeys, the only equipment really used was six kids watching and working in relays and an adult to take down the tree. I have never heard such a story as this one.

It was a different time

It was a different time. In this particular phase of transitional beekeeping, destroying box hives and robbing bee trees was not anything unusual. Today, clearly things have changed. Beekeeping continues to be in constant transition.

Part 2, next month

Dear reader, thank you for staying with me to this point. Next month, I would like to continue this discussion as beekeeping continues to evolve. Exactly what is medium brood foundation and why do I want it? How many section scraping knives should I own? How many Hoffman frames do I need? Why are there sometimes hooks on my foundation sheets? And comb honey, oh my stars, the herculean efforts earlier beekeepers expended to get the delectable comb product. Plastic. Chemicals. Mites. Pesticides. We have been very busy changing and adapting. That’s a lot of transition. Until next month, thank you so kindly for reading.

Dr. James E. Tew

Emeritus Faculty, Entomology

The Ohio State University and

One Tew Bee, LLC

tewbee2@gmail.com

http://www.onetew.com

https://youtu.be/ewYYqTXXVOs

Follow our Bee Talk podcast at: https://www.honeybeeobscura.com

1Scriptsit is Latin that roughly translates to “wrote”

2Seeley, Thomas D. 2019. The Lives of Bees, The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the Wild. Princeton University Press. Princeton and Oxford. 353pp.

3Colonies that were being transferred were frequently “drummed” but that is yet another old process that is now obsolete.

4At antique dealers today, these lining boxes are highly collectible. They are always simple and always expensive.

5Seeley, Thomas D. 2016. Following the Wild Bees, The Craft and Science of Bee Hunting. Princeton University Press. 164pp

6To me, this is a very interesting comment. At some point, does a colony under attack relinquish the defensive mode and shift to saving enough honey stores to make a start at another location? Remember, the nest cavity has been destroyed. Would that destruction not make more survival sense than fighting to the death at the home nest location for an obliterated cavity? Could the queen fly – at all? And consider the average wild nest size. Most likely, the population was small compared to our big, managed colonies of this time. Not as many defenders to sting beekeepers. Let’s both think about this some more.