by Sarah Gabric

The Latvian people are passionate about honey bees and beekeeping.

Latvia sits nestled between Estonia to the north, Lithuania to the south, Russia to the east, Belarus to the southeast and the Baltic Sea to the west. About half the geographic size of Ohio, Latvia has a current population of approximately two million people, about 25% of whom are Russian.

My husband and I traveled to Latvia early this year to visit friends and while there did some exploring of local apiculture. We stayed in the capitol city Riga, which is, latitudinally speaking, about as far north as Juno, Alaska. While there we visited three shops dedicated solely to the sale of bee related products. We encountered, at every market stand, pharmacy, souvenir shop, and corner store, bee-inspired toys, decorations, and images, as well as honey and products that utilize honey, pollen, propolis, etc. in their ingredients.

The Latvian people prize the honey bee and seem deeply invested in the health and medicinal benefits derived from apiculture. They consume honey, pollen, propolis (good for toothaches), bee bread (helps the body heal after illnesses), and royal jelly directly as well as using the above in both food products and creams, suppositories, balms, cosmetics, and tinctures. Additionally, some Latvians practice apitherapy (also known as bee venom therapy or sting therapy).

A month or two prior to our visit, we began communicating with Juris Steiselis, Chairman of the Latvian Beekeepers’ Association, and beekeeping ambassador extraordinaire. We met-up with him on our second day in Riga at Medus Veikals, a local beekeeping emporium. Who knew one could fit so many honey bee-related items into a room no bigger than 20ft x 30ft? Medus Veikals (medus means honey), is owned and operated by Janis Malcenieks a third generation beekeeper, and supplies its customers with everything from the practical; smokers, hive tools, wax foundation and colorful jackets and veils, to the whimsical; candles in every imaginable shape and size. Medus

Veikals did a brisk and steady business during the 30 minutes we were there. Most customers did not browse but seemed to be coming in for the specific reason of purchasing a product they were familiar with but maybe had run out of, as though their stop at the honey shop were merely an errand tucked in among a list of others.

After spending half an hour talking with Juris, Janis (the proprietor), and Janis Snikvalds (a beekeeper and export manager of the Latvian Beekeepers’ Association) we headed for the countryside in Juris’ car. Janis, pronounced Yan-ees, is a very popular name in Latvia, meaning God is Gracious. We encountered the name, which translates to John in English, countless times. In the remainder of this article when I mention Janis I am referring to Janis Snikvalds.

As we left downtown Riga, the oldest section of which dates back over 1,000 years, a city of grand, palatial architecture, magnificent, ancient cathedrals, and countless cafes, bakeries, and restaurants we jostled over cobblestone streets inlaid with tram tracks and pavement. Our car wove in and out of traffic patterns either too complex or erratic for me to follow in a jolting but unhurried fashion. From the city proper we passed through more modest neighborhoods and on into an area of monotonous, hulking, concrete apartment buildings, one after the other, in a seemingly endless succession. These structures are remnants of the Soviet era and are said to be as identical on the interior as they are without.

As we continue on the landscape begins to soften, less manmade geometry and more of the natural world with its gentle curves and tangle. The colors here are familiar to me, as they are similar to the colors of Maine, the neutral nivian colors of winter; lichen-grey, aspen-silver, dusty-dun, amber-rust, deep spruce-green, the stunning white of snow and birch bark set against the dark black of soil. The air is heavy and thick with moisture. The temperature a steady 33°F.

At this time of year, early Spring, the Latvian people tap the maple and birch trees and drink the sap. The saps, berzu sulas and klavu sulas respectively, are sold in the grocery stores and as well as being refreshing with the slightest hint of sweetness are considered a spring tonic, cleansing and invigorating.

After about 40 minutes of driving through forests and fields interspersed with small villages we arrived at the home of Lolita Rudzite in the town of Lielvarde. In her front yard, in a neat row stand 18 colorful hives. Latvian hives are larger versions of the more familiar (to Americans) Langstroth hive.

Latvian hives came into being in the late 1920s as a result of the work of the man known today as both the Latvian Langstroth and/or The Father of Latvian Beekeeping, Professor Peteris Rizga (1883-1955). In 1908 Rizga emigrated to America and worked in quarries with his brother to earn enough money to purchase two farms. This they succeeded in doing. On one farm they raised poultry, on the other bees. During this time Rizga earned both a bachelor’s and master’s degree from Boston University. Rizga returned to Latvia in 1922 (Latvia had won sovereign independence from Russia in 1918) and began working at the University of Agriculture. At that time there were no national standard hives and most hives were bulky and unwieldy. In response to this situation and after having kept honey bees in Langstroth hives in America, Rizga created three new types of hives, the surviving hive design, described below, remains today as the national Latvian standard.

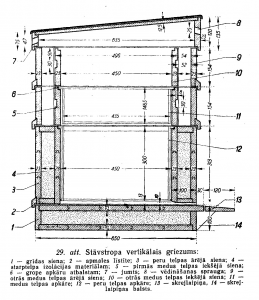

The Latvijas stavstrops or Latvian standing hives (referring to the fact that the hive stands vertically as opposed to laying horizontally as traditional log hive sometimes did), the standardized hive created by Prof. Rizga is composed of one brood box measuring 25 inches in length X 25 inches in width X 12 inches in height. The interior volume of the brood box, which holds 15 frames (171⁄8 inches in length by 11¾ inches in height), is equal in capacity to two deep 10 frame Langstroth hive boxes. The brood box is double walled in the front and back. The foundation used in both the brood boxes and honey supers are almost exclusively wax (as opposed to plastic). The honey supers are almost exactly half the size of the brood box. Over a strong season most beekeepers hope and expect their colonies will fill three or more honey supers, each super containing up to 55 lbs. of honey

As it was still early Spring when we visited, Lolita’s hives were

condensed, her colonies occupying eight to 12 frames within the brood boxes. The bees were covered with newspaper and cloth and topped with a pillow which served both to insulate and ventilate the hive. Additional insulation was provided by newspaper covered frames filling the spaces just beyond the brood frames facing the side hive walls. Topping the stack was the familiar (though dimensionally larger) telescoping cover.

Lolita keeps Buckfast (Apis mellifera linguistica) and Carniolan (Apis mellifera carnica) honey bees. Both are dark colored bees, originating from cooler climates, and seem well suited to Latvia’s

climate. This partially evidenced, by the fact that Lolita, like most other Latvian beekeepers, experiences less than 10% winter loss. This year she has only lost 2.5 % of her colonies!

I am told that the honey bee races most favored in Latvia are Buckfast, Carniolan, what they call Finnish Italians (owing to the fact that these particular Apis mellifera linguistica are imported from Finnland and are thus adapted to the Nordic climate). The German black bee also called European dark bee, Norwegian brown bee and Russian black bee, (Apis mellifera mellifera) was considered, 20 years ago, Latvia’s aboriginal bee. This race of bees is not currently popular in Latvia owing to its aggressiveness.

Lolita demonstrates the gentleness of her bees by lifting the insulating cloth beneath the pillow and lightly tapping the backs of the hundreds of bees who have come to the surface of the hive, into the brisk air and have struck the intimidating posture of heads down, abdomen raised, sting out, wings fanning. Janis breathes deeply as we peer into the hive exalting in the smell of venom. I try but can’t catch a whiff of what to him is a sweet, distinctive and familiar odor. Lolita, of course does not get stung, (none of us do) and the bees, though full of apparent sound and fury, are mostly disinterested in our doings.

Lolita has been keeping honey bees for 41 years. She, at this point, keeps 200 hives, though before her husband (also a beekeeper) passed away they had as many as 300 colonies. She keeps perhaps 10 in her front yard, the rest are in out-yards, apiaries whose location is, if not secret, information closely kept.

Lolita says that her bees rarely swarm as a result of preventative practices. She, as is customary here, feeds only in the Fall. Additionally, she treats for mites only in Autumn. Varroa mites first arrived in Latvia in 1977. Initially beekeepers were required by law to burn hives infested with Varroa. Today they are mainly treated using formic and oxalic acid. There are no tracheal mites reported to exist in Latvia nor has the small hive beetle made its way that far north, though the beekeepers we spoke with were well aware of their existence and the potential encroachment. Juris said that the percentage of hives affected by American and/or European Foulbrood was around 4%.

The Latvian people appreciate varietal honeys. When we visited honey shops there were a few amalgam honeys; Spring, Wildflower, and Forest Blossom. The rest were specifically labeled and every honey vendor practically insisted you sample the array of varieties. These included Canola, Heather, Linden, Hogweed and Wild Raspberry.

The bees are said to generally take their first cleansing flights March 23-25, weather permitting. The major nectar flows in Latvia begin in April with tree blossoms, maple, willow and orchard trees. This time of year can be tricky for bees and beekeepers alike in that April and the first half of May tend to rainy and cold. The next major flow commences with the blooming of the rape or canola seed (Brassica napus). At this time of year, late spring, some people take their hives to the forests to capture the flowering of wild raspberry canes (Rubus sp.). Some bee keepers also encourage their bees to forage on Hogweed (Heracleum sosnoskyi) which was introduced during the Soviet Era, has become invasive and produces a honey with a distinctive odor and flavor similar to daffodils. Linden, also known as Basswood and Lime (Tilia sp.) bloom in mid-June. The next major flow comes in July with buckwheat (Fagopyrum asculentum). Some beekeepers take their hives to heather (Calluna vulgaris) fields from July 25- September 10th. Around the year 2000 goldenrod (Solidago canadensis.) which had been kept as a decorative garden plant since the 1950s ‘escaped’ and its true nature, that of an invasive, opportunistic propagator began to flourish. It has now taken hold, filling fallow fields and waste areas such as ditches and wind breaks, providing the honey bees with an addition floral source for nectar and pollen from July through September.

In Latvia the honey bees begin to go into the Winter cluster in October and November. However, the weather is highly variable in this geographically diverse region. As Juris explains it, “The cold comes down from Siberia. The warm comes in from the Baltic Sea. These airs fight.” Two regions separated by 150 miles may experience bloom differentials of up to two weeks. Additionally, Latvia is experiencing the same dramatic shifts in weather patterns as the rest of the planet, “The winters used to be colder, longer, more snow”.

After visiting on of Lolita’s out-yards we return to her home, tour her processing rooms, and enjoy a delicious, gracious lunch. Lolita’s honey house is immaculate, not a sticky surface or propolis stained instrument in sight. Here is where she extracts honey and bee bread and where she bottles and labels honey, propolis, pollen and bee bread. Bee bread, a relative rarity in the United States is ubiquitous in Latvia and is consumed for its purported health benefits. Being fermented, it is rather sour tasting as compared with the chalky sweetness of pollen. Lolita also melts honey and makes candles as well as fermenting propolis to make tinctures. Lolita and her business are, as they say, the complete package, and her operation appears, at least to this outsider, to run as smoothly as silk on a sunny day.

Though honey sales within Latvia seem brisk, the ability to export honey is limited. I am told that when Latvia was under Soviet rule and much of the honey and honey-relate dproducts produced were consumed by Russia, a beekeeper could earn a good living and then some. Juris tells us, “I bought my first car with [the money earned from] 30 beehives”. Janis seconds this, saying, “My father built our house on [money earned by collecting and selling] pollen”.

Latvia is a country whose epic history is dominated by occupation. Just in the last 100 years Latvia was occupied by the Russians, from whom it won independence in 1918. This independence was then interrupted in 1940 when WWII broke out and Latvia was forcibly reincorporated into the Soviet Union. It was invaded and occupied by the Nazis in 1941 and retaken by the Soviets in 1944-5. Latvia again reclaimed its independence in 1991 and was officially invited to join the European Union in 2004.

I am told that though life was much different, and in some ways more difficult, for instance there were regular scarcities of common goods, under Soviet rule, keeping bees was a profitable undertaking. At present, Latvians cannot sell to Russia because of the EU boycott resulting from Russia’s recent aggressions toward Ukraine. This boycott is difficult for honey sales and export agencies. Entrepreneurs, agencies and associations are actively looking to expand their markets abroad.

Despite the decline in export opportunities of late the popularity of beekeeping in Latvia appears to be on the rise. Juris shared the following statistics gathered by the Latvian Beekeepers Association in 2016. At present there are approximately 4,000 active beekeepers and 2,945 officially register apiaries in Latvia. Of these 2,945 apiaries 40% keep 1-14 hives, 25% 15-29 hives, 20% 30-49 hives, 10% 50-99 hives, 2% 100-149 hives and 3% 150 + hives. From these statistics it is clear that the majority of beekeepers are running relatively small operations, with 85% keeping 50 hives or less.

Of these beekeepers 32% are women. In aggregate, the ages of Latvian beekeepers likely mirror those in the United States. Nearly half of the beekeepers are between 40-60 years old. I am told that there has been, in just the last three years, 800 new beekeepers added to the Latvian ranks and that beekeeping classes are very successful. This renewed interest may in part be linked to the financial crisis which hit hard in Latvia in 2008-9. During this recession many people lost their jobs and began looking to more traditional ways of earning money.

When our comfortable modern ways of life become threatened and disrupted by financial, social, and/or environmental crisis we often revert to more fundamental, time-tested, and traditional ways of life. These, often more holistic, ways of interacting with our world generally bring us closer to that world. We learn again to rely on our intuitive, inventive resourcefulness, our penchant for working with – with our hands, with our land, with the creatures with whom we share the land. I can think of few practices more perfectly aligned with supporting these oft underappreciated gifts of human ingenuity and even fewer whose reward is as sweet and satisfying as beekeeping. The Latvian people know this, honor this, celebrate this, and in this we can only applaud and hopefully follow suit.