Click Here if you watched/listened. We’d love to know what you think. There is even a spot for feedback!

Going Down the Road

By: Tracy Farone

Proper transport of agricultural livestock is a familiar topic amongst veterinarians and largely regulated by the USDA. Animals move for a variety of reasons, herd restocking, breeding, shows, and fairs, but “going down the road” in my profession, often refers to animals being loaded up and transported for slaughter. Even at this point in an animal’s “career,” there are volumes of guidelines and regulations in place to assure proper treatment, safety, and the reduction of stress of the transported animals. Veterinarians study the “medicine” of transport for animals to address the stress, injury, and exacerbation of disease that improper transport may cause. In contrast, honey bee colony movement within the U.S. is largely controlled by States’ apiary programs/inspections and “going down the road” in this case is purposed to further propagate life through pollination.

While the majority of our honey bee colonies in the United States are designed to be migratory hives, most beekeepers in the U.S. are small scale operations that are not typically designed for movement. Migratory beekeepers may have hundreds to thousands of small to mid-sized hives bolted down to pallets. Pallets which can be moved with fork trucks, a trained crew, and then hauled on big rigs. Movement is a typical day’s work for these folks. Most backyard beekeepers may have several large honey-producing hives, a pick-up truck, and a dolly. Most small-scale beekeepers never have had to consider the movement of their hive/s. Until you do…

Due to new construction coming into the area, I recently had to move all hives from one of my apiary sites to another. While I had helped migratory beekeepers before, I now had to plan the movement of my own (15 big fat honey hives) yard. So, life experience has provided me with yet another topic I thought I could share with small-scale beekeepers just in case one may find themselves in a comparable situation. Not unsurprisingly, I discovered that many of the things that should be considered in the movement of any agricultural animal also applies to honey bee colonies.

Here are seven important steps to consider when planning and executing a small-scale move within a single operation.

- Pre-planning

Before the move be sure you have researched any laws or regulations you may need to follow to move your bees. If you are crossing state lines, you will likely need a state health inspection before movement of bees or equipment. Some municipalities may also have ordinances on honey bees or the number of colonies you may have.

Also, before the move, evaluate and prepare the new site so that the new hives can be placed into the apiary area as easily as possible, i.e., have ground leveled, weed barrier down, fencing and hive stands in place.

Consider any biosecurity issues, what are the possible risks? Bears? Are there any other hives in the new area? Do not move any diseased hives. Keep Varroa in check. Consider any other bee-related equipment that may need packed. Be sure to properly close down the previous site, leaving no debris behind.

Consider the new environment. Is the forage in the area adequate for the new hives?

Understand that this evaluation and preparation will take an investment of time and work, but reducing stress to your bees, you and any team members will be well worth the effort. - Timing

Time of day: Movement of colonies must occur at night. Waiting until after sunset assures us that all the bees are in the hive and they will be less active during the move. (Figure 1) It also means you will be doing this in the dark- bring flashlights! Redlights may be best, so as to not attract any stray honey bees to artificial lighting.

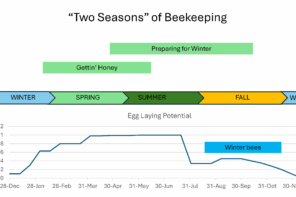

Season: If extra honey supers are on the hives you may want to consider extracting the honey before the move to reduce hive size and weight. For the move try to pick a fair, mild day without precipitation or high winds, and temperatures between 55-85°F degrees. In seasonal areas, if possible, move colonies in the early Spring when colonies are still smaller and have not established a foraging pattern for the season yet. Moving in Winter or in the middle of a nectar flow would not be advisable.

Time on the road: Consider the amount of time bees will be in transport. Minutes? Hours? Longer times can cause the bees to overheat or become chilled if air exposure is too much or too little. Plan a safe place/s to stop along the route if needed. Hopefully for a small-scale move, you will not have much distance to travel. - Closing the entrances

After the sun goes down and bees are in their boxes, don your bee vail/suit and gloves, and close all (top and main) entrances. (Figure 2) Fitted wood blocks or duct tape are helpful to secure the entrances. - Securing the boxes

Use rachet straps to secure boxes together – bottom board to top outer cover. Be sure to have enough straps to secure the boxes onto the transport vehicle. Place boxes firmly together on the transport vehicle to reduce slippage and reduce wind exposure. (Figure 3) - Heavy lifting and moving

Here is the fun part. How do I get the bees, perhaps big fat honey hives, onto the truck? Well, I hope you can recruit a few strong and bee-crazy friends to help. Trucks with lift gates, dollies, a big-wheeled wagon, and strong friends to get the bees on and off the truck are helpful. (Figure 4)

Have everyone wear beekeeper PPE to prevent against stings. Even though you may have closed the entrances a few stray bees will be flying around and they may not be incredibly happy. Have some sting first aid on hand. Once in transport drive carefully and have hive identifications or any licenses available. Having at least one trailing vehicle is also helpful to keep an eye on how well the hives are riding to prevent any potential transport mishaps. (Figure 5) - Removing restraints

Once the new colonies are in their new location, understand that the shuffled colonies may not be in a particularly good mood immediately. Give them a few moments to settle from the transport and then carefully remove straps and the entrance restrictions. It is important to establish airflow through the hive relatively soon after arrival. - Adjustment

Hives moved to a new location will need several days to “recalculate.” You may witness re-orientation flights (bees flying up and down in front of their hives), and if there are other hives in the area, robbing behavior. Adding robbing screens/entrance reducers to existing hives in the area may reduce the effects of this robbing behavior until the new hives establish typical foraging in the environment.

A Successful Move

So, what about my move? Well, I am happy to report that with the help of a team of students, several strong maintenance crew members, a truck with a lift gate, and several dollies, we were able to successfully move 15 (big fat honey) hives about 12 miles to a new location all within one Commonwealth. We had ideal weather and a nice night for a move. We did have to move the hives during the Fall nectar flow. Five established hives in the new location were subject to some robbing by their new neighbors. After about a week, a new normal was established throughout the yard with their beekeeper playing Robin Hood to balance the colonies and prepare for Winter at a new home base.

PS Do not forget the bee shed! (Figure 6)