Click Here if you listened. We’d love to know what you think. There is even a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

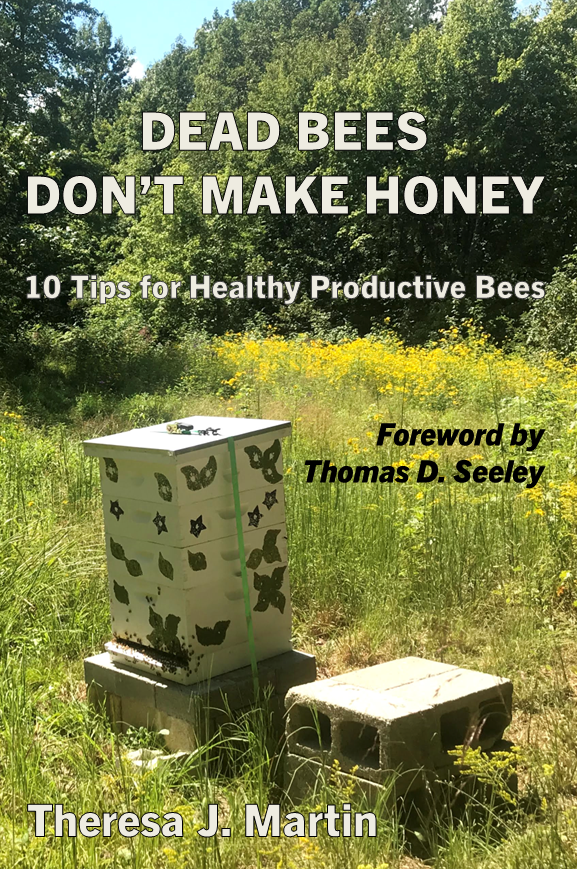

Theresa J. Martin is the author of Dead Bees Don’t Make Honey: 10 Tips for Healthy Productive Bees, which includes a Foreword by Dr. Thomas Seeley. Theresa has achieved 99% colony survival and honey production that is twice the local average in her seven years as a beekeeper, with 20–25 colonies in Kentucky. She can be reached at theresa@littlewolf.farm

Avoid Overly Disturbing the Colony

Theresa J. Martin

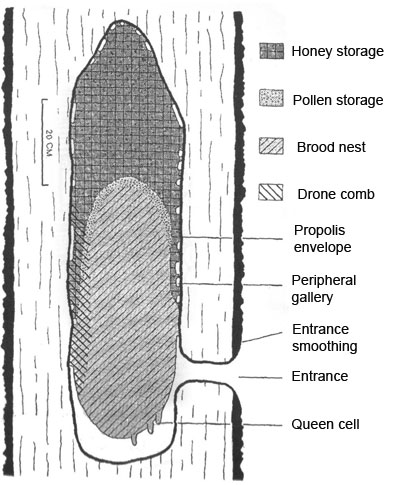

Honey bees evolved over thirty million years to construct a home that is perfectly suited to their needs. Inside a cavity, the colony constructs a 3D oval shaped brood nest with worker brood, drone brood, honey, and pollen located where it takes the least amount of energy to access each resource (Figure 1). The colony designs their home for efficient thermoregulation, which is the process by which the bees heat and cool the brood nest to keep it at a near constant 95°F, regardless of the outside ambient temperature. The brood nest shifts and migrates within the cavity to take advantage of changing outside temperatures and to keep in constant contact with stores.1

Honey bees are one of only a few organisms that build the interior of their homes from material excreted from their own bodies. Wax comb is critical to a colony’s well-being and is “not only living space, food store, and nursery, but also an integral part of the superorganism: skeleton, sensory organ, nervous system, memory store, and immune system” (Tautz, 2008, p. 157). Creating new wax is energetically expensive and requires significant resources. It takes 6–8 pounds of nectar or syrup for bees to produce one pound of wax. Young worker bees do most of the comb building, excreting wax from eight glands located on the underside of their abdomens. Cell construction is methodical with groups of comb-builders depositing wax in several locations simultaneously, while always building the structure towards each other. When the sections meet, the workers join them so perfectly that it is difficult to see the seam between sections.2

The nests of unmanaged colonies are rarely disturbed. Colonies usually locate nests high in trees or structures where they are less vulnerable to natural predators such as skunks, raccoons, opossums, honey badgers, and bears (Figure 2). While trees fall from high winds and some predators are strong climbers, these disturbances are infrequent.3

Unmanaged honey bees select and construct their home perfectly suited to their needs, and no one interferes with their design. Nor does anyone disturb them as they go about their lives.

Disruption Common in Managed Hives

Many beekeepers are taught to reorganize the brood nest in a variety of ways. For example, beekeepers attempt to encourage wax building on the side of a hive where there is not yet drawn comb by moving undrawn frames between drawn frames. A popular swarm prevention technique is to open up the brood nest by alternating frames of undrawn comb with brood frames. Checkerboarding is another swarm management method where the beekeeper alternates empty drawn comb with honey filled frames in the two boxes above the brood box. Finally, beekeepers sometimes reverse deep brood boxes in the spring to move the brood nest down, as a swarm prevention technique.4

Put Everything Back As It Was

It is paramount that beekeepers perform periodic inspections to ensure colonies are disease-free, queenright, and productive. Beyond this, beekeepers focused on healthy productive bees generally put everything back in the hive as the bees designed it.

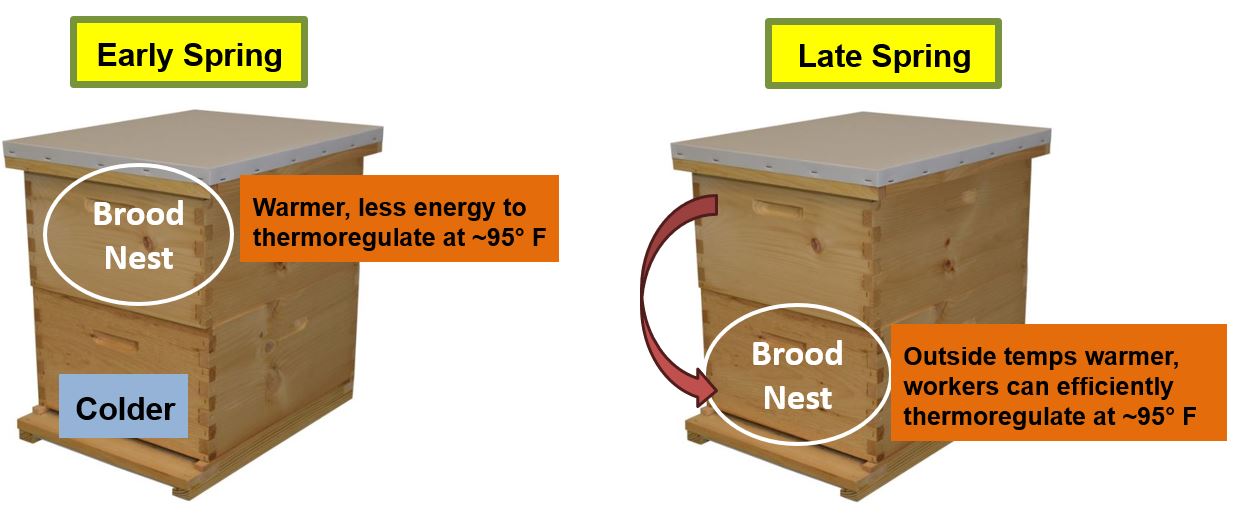

For example, in Spring if the queen is laying in the top box of a double deep, the beekeeper does not reverse boxes. Instead, the beekeeper recognizes that heat rises, so the top box is the warmest location and most efficient place for the workers to thermoregulate the brood nest at approximately 95°F, while the outside temperature fluctuates dramatically. Research shows colonies place their brood nest in locations where it requires the least amount of energy to care optimally for the brood and they dynamically relocate the nest to take advantage of changing conditions. Weinberg (2023a) provides “evidence of plasticity in honey bee phenotype in response to changing environmental conditions” (p. 3). As Spring temperatures warm up, the queen and workers migrate down to the bottom box (Figure 3).

Similarly, regarding drawing comb, the beekeeper focused on bee health trusts that the bees will draw wax in the most energy-efficient progression.5 The beekeeper may notice that the workers are building comb on the side of the box that receives more sun. The colony congregates on the warm side so they can simultaneously and more efficiently perform multiple functions, such as wax building, thermoregulating brood, and feeding larvae. The beekeeper recognizes that moving frames around is disruptive, which slows it down in the long run.

Methods for Less Disturbance

As a beekeeper focused on bee health as the optimal pathway to increased productivity, I generally trust that the bees know how best to build their own home. By not rearranging their world, I avoid adding stress and making it harder for them to thermoregulate, raise brood, and draw wax.

Inspections are critical for visually verifying colony health and productivity. I try to execute inspections as effectively as possible to minimize the time I am inside the colony (Figure 4). To increase the efficiency and value of each inspection, I use several tools.

First, I consult prior inspection notes and consolidate actions into a single intrusion (Figure 5). At the same time, I try to remain flexible because once I open the hive, conditions are not always as I expected.

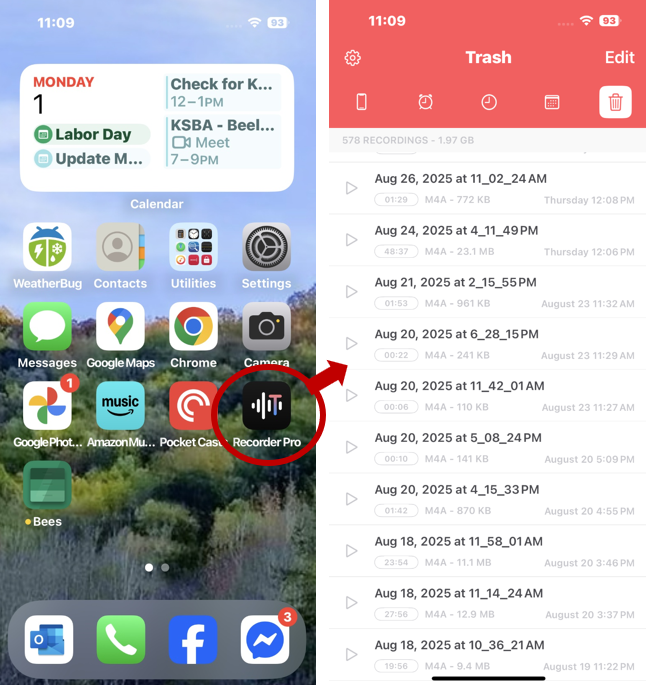

Second, I audio record myself during inspections. As a solo beekeeper, I needed a better way to document what I saw during inspections. I have a poor memory, and 5 minutes after closing the hive, I cannot remember what I saw. To solve this problem, I audio record myself using an app on my phone, describing what I see and what I did. When I get home, I play the recording back at fast speed and make notes in my bee journal of important observations (Figure 6).

The use of temperature sensors gives me a strong indication of the queenright status of the colony and where the brood nest will be located. In essence, the temperature sensors provide a sort of “vision” into the internal workings of the colony, representing whether all is normal or there are likely to be issues. I detailed my use of temperature sensors in a 4-part series in the April, May, June, and July 2025 issues of Bee Culture Magazine.6

Finally, I weigh my hives periodically using the Cabela 330 lb. digital hanging scale. I lift the back of the hive, then double the displayed weight to calculate the approximate total hive weight. This external directional data allows me to pull fewer frames to assess overall stores.

Honey bees are the epitome of efficiency and know how to most efficiently construction and maintain their own home. Beekeepers can reduce colony stress and avoid creating extra work for their colonies by avoiding unnecessary disruption. This in turn allows colonies to invest precious resources in value-added activities, such as stockpiling honey for the colony and for the beekeeper.

Theresa J. Martin is the author of Dead Bees Don’t Make Honey: 10 Tips for Healthy Productive Bees, which includes a Foreword by Dr. Thomas Seeley. Theresa has achieved 99% colony survival and honey production that is twice the local average in her seven years as a beekeeper, with 20–25 colonies in Kentucky. She can be reached at theresa@littlewolf.farm

REFERENCES

1Seeley & Morse (1976) made external observations of 39 natural tree cavities and dissected 21 of those cavities. Their research provides our best understanding of a typical unmanaged nest. Seeley (2019) covers thermoregulation in the chapter called “Temperature Control” in The Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the Wild. In addition, Weinberg et al. (2023a and 2023b) studied the effect of heating and cooling brood nests to learn how the colonies respond. The studies concluded that in both heating and cooling situations, the colony relocates the nest in various ways and consumes more honey due to increased efforts to perform heating and cooling functions.

2Seeley, T. D., Morse, R. A. (1976). The nest of the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.). Insectes Sociaux, 23(4), 495-512. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02223477

Seeley, T. D. (2019). The Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the Wild. Princeton University Press.

Weinberg, I. P. (2023a). Honey bee ecology in a changing landscape: Comb phenotype, nutrition, and self-organization in response to exogenous pressures (Doctoral Dissertation, Tufts University).

Weinberg, I. P., Wetzel, J. P., Kuchar, E. P., Kaplan, A. T., Graham, R. S., Zuckerman, J. E., Starks, P. T. (2023b). The organizational impact of chronic heat: diffuse brood comb and decreased carbohydrate stores in honey bee colonies. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 11, 1119452. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2023.1119452

2Tautz et al. (2008) provide a fascinating chapter about comb called “The Largest Organ of the Bee Colony — Construction and Function of the Comb.” The pictures provided are fantastic.

Tautz, J., Heilmann, H. R., Sandeman, D. (2008). The Buzz about Bees: Biology of a Superorganism. Berlin: Springer.

3Seeley (2010) explains that when choosing their own home, honey bee colonies prefer cavities with entrances approximately 21 feet high off the ground, presumably to protect themselves from ground dwelling predators (p. 52).

Seeley, T. D. (2010). Honeybee Democracy. Princeton University Press.

4Burlew (2012) provides good definitions for several swarm prevention techniques, such as opening up the brood nest and checkerboarding.

Burlew, R. (2012, March). How to open up the brood nest. Honey Bee Suite. https://www.honeybeesuite.com/how-to-open-the-brood-nest/

5Pratt (2004) studied how colonies optimally decide to invest in energetically expensive comb building balanced against their need for more space.

Pratt, S. (2004). Collective control of the timing and type of comb construction by honey bees (Apis mellifera). Apidologie, 35(2), 193-205. https://doi.org/10.1051/apido:2004005

6Martin (2025) describes her use of BroodMinder temperature sensors in a 4-part series.

Martin, T. (2025, April, May, June, July). Take the Temperature of Your Colony: Part 1-4. Bee Culture Magazine.