Click Here if you listened. We’d love to know what you think. There is even a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

And Yet a Few (More) Comments on Honey Bee Swarm Biology and

Management (Part 2)

The Swarm in Transition to a Colony

By: James E. Tew

In the hive

In the April 2025 issue of Bee Culture, I spent my article space discussing some aspects of elementary swarm biology of honey bees before they leave the parent colony. As I ended that piece, I left the hypothetical swarm roaring from the hive and organizing itself in the air near the hive. I suppose a discussion of honey bee swarming could be divided into sections: (1) the swarm still in the parent hive, (2) the swarm in the air, (3) the swarm at the bivouac site also called the hanging swarm, and (4) the swarm at the new home site. At this point, my hypothetical swarm is at step two – in the air.

Outside the hive

When the swarm departs, what a ruckus goes on and how quickly it happens. Thousands of bees everywhere – flying, crawling, running, crashing into each other – organized chaos. To the human observer, it looks random. How could there be any order to this confusion?

Though flying honey bees can hover, they seem to only do it for a short while. For instance, when they pack pollen, they will briefly hover near the blossoms being pollinated. Or when they are challenging you, they will sometime hover near your face seemingly trying to intimidate you.

So, here’s the situation – in short order, thousands of bees must exit a reasonably small nest entrance. They can’t all do it at once so what are the first bees already outside to do? Sit on the ground or surrounding foliage? Some do, but most don’t. Amass on the hive? Some do, but not all. Hover in a holding pattern for several minutes? No, bees don’t seem to hover very long. How do waiting bees outside the hive keep themselves busy as they await the word to depart? They randomly fly near the hive until all are outside and the bee word is pheromonally given to move out. All that confusion outside the hive is just a holding pattern until all the departing bees can queue up in preparation for the short trip to the temporary site.

But wait, the mission is aborted

After describing all this process and its seemingly related confusion, something goes wrong. Sometimes it happens. What, the queen didn’t leave? Did the swarm issued too late in the afternoon? I really don’t know the bees’ reasons, but it is not all that uncommon for the departing swarm to call off the mission and return to the hive. Many has been the beekeeper, frantically getting equipment together in preparation for hiving the swarm, only to watch the swarm return to the parent hive. It’s a confusing moment. Bees everywhere, the humming cloud slowly drifting away from the hive, when nearly imperceptibly, the swarming bees seem – ever so slowly – to begin to drift back to the parent hive. The bees changed their collective minds. It is the very rare human who knows why. The bees literally roar back into the hive, clustering on the front. As quickly as it started, it stops. All swarming departure procedures are not successful.

You’re not home free

But you are not home free. This colony is primed and loaded to swarm. Something went wrong today, but tomorrow – or someday soon – this colony will try again. If ever a beekeeper was given notice that a swarm was about to go, this aborted swarm is that notice. And yet, what to do at this point? If I, the beekeeper, make a typical colony split, there is an excellent chance the parent colony will still swarm. If I make heavy splits or divide the colony in halves, I may very well only get multiple smaller swarms. Destroying queen cells or caging queens will not necessarily stop the advanced swarming impulse. While there may be radical procedures I could try, such as removing all the brood,1 simple procedures are probably just as effective. I suppose I would make 3-4 splits; making sure that each split had queen cells. There is a great chance that I will get several small swarms from this procedure, but otherwise, I am nearly certain to get one large swarm. This is one of those situations in life where one tries to do what is least wrong rather than what is exactly right.

Now back the swarm

The next day, early May, dawns bright, warm and blue. Just after lunch, roughly following the events outlined in April’s BC swarm article, the colony again tries the swarming behavior. This time, they get it right. Bees pour from the hive. Somewhere in the mass, the weight-reduced queen is pushed along. Outside the hive, her pheromones are perceived and nearby flying bees expose their Nasanov glands. The queen is out! All systems are go! About half of the bees leave during the excitement. Even though she is now much lighter, the queen is still a rather clumsy flier. She zooms around – probably taking orientation flights. Her pheromone field is perceived by other flying worker bees and they expose their Nasanov glands in flight. The swarming bees assume a generalized form and slowly move away from the parent hive.

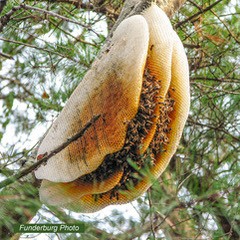

At some point, usually within 50 yards of the parent colony, the queen settles on something – something seemingly random. She may actually drop all the way to the ground or she may gain altitude until she is high in a nearby tree. No rhyme. No reason. Surrounding worker bees put the notice out by exposing their scent glands that the queen is at this location. At first only a few bees scent, but increasingly more and more bees scent at the location the queen has selected. More and more bees accumulate. Within only a few minutes, the cluster forms with the queen somewhere in or on the mass. So long as her chemical presence is known, the cluster is content. Everything at both the swarm site and the site of the parent colony settles down and things look as though nothing had happened.

The primary swarm

This nice, big, first swarm is called the primary swarm. It doesn’t get any better than this. This is the swarm that beekeepers want to hive. This is the swarm that makes beekeeper stories. This is the swarm that beekeepers fall from ladders to gather. With even an average nectar season, a 5-pound swarm will develop into a prosperous colony that should easily survive the upcoming Winter.

This primary swarm will hang at this temporary site anywhere from a few hours to several days before taking flight to the new home site. While hanging at this temporary site, nectar foragers will make collecting trips, but mainly scout bees are searching for a suitable home site.

Commonly, bees with pollen loads are seen in the swarm cluster, but these bees are only converts to the swarm event. Hanging swarms, with its powerful chemical allure, will attract returning foragers from the parent colony or even other colonies. Oppositely, some of the original bees to leave with the swarm will lose the urge and will return the parent colony. I have seen colonies nearly empty of bees after a large swarm has just departed, but mystically the parent colony would repopulate itself within a few minutes with enough bees to maintain the original colony. Some foragers simply returning home from an unexciting foraging trip, change their mind and decide to “run off with the circus” while other bees that left with the swarm, give up the project and return the parent colony. Not wanting to be left out, drones are on the swarm trip, too. I don’t really know what purpose they serve in the new colony, but they are always in the swarm population. No doubt, there is some need they are meeting, but I have no clue what those needs might be.

Scout bees

Scout bees fly from the surface of the swarm and search for a cavity having:

- A cavity size of about one cubic foot

- Dark inside

- A defendable entrance

- Nothing else living there (no birds, no ants, no squirrels)

- Dry

- Normally not in the ground

As hollow trees have become fewer and fewer, scout bees have increasingly adapted themselves to human urbanization by finding cavities in the walls of our buildings. It must be a good deal for the bees. Warm and protected, but it drives homeowners crazy.

Scout bees do their scouting thing and return to the swarm surface where they dance giving information about the quality and direction to the prospective new home site they have found. Scouts must campaign for their particular finding. Other scouts are recruited to visit the new digs and they come back and add their dance comments to the mix. At some point – hours or even days pass – the majority rules and a swarm decision is made concerning the new home site. Just as they did within the parent colony, the hanging swarm becomes “flighty.” It begins to lose it compactness and more and more bees take flight.2 A bit like a helicopter slowly rising in the air, the swarm will become airborne, position itself, and suddenly take off – vanishing. At that point, it is lost to the beekeeper.

Strange as it may seem

As strange as it may seem, the following event frequently happens. A beekeeper gets the call to come for a swarm which she/he dutifully does. The swarm seems to move in nicely and all surrounding observers are impressed with the beekeeper’s Pied Piper ability to handle bees. Arrangements are made to return late in the afternoon to retrieve the newly filled swarm box – only to find it empty upon the return. I feel comfortable guessing that what is happening in this case is that – even though the swarm was given a nice bee box – after settling within the box, the site recruitment dances began again and the swarm decided to go with the dancers’ suggested site – not with the new swarm box. It makes no sense to us, as beekeeping humans, to leave a perfectly good beehive and move to a cavity in the wall of a house or a hollow tree, but bee swarms decide to do it all the time. It is always a good idea to have a queen cage on the swarm-collection-run… just in case you happen to see her; but you should know that I have even had a few swarms leave a caged queen to go to the new home site. (I don’t know if they stayed there without her or if they sheepishly returned to the parent colony.) All swarming procedures are not successful.

At the new site

At the new site, everything will soon change. Frequently a beekeeper will get a call that, “a bunch of bees have landed on the side of my house, near the chimney.” That’s probably bad news. If the swarm has landed and the queen has moved into the wall cavity, things are pretty much over. The beekeeper simply scraping bees from the house wall into the swarm box will not entice the queen to come out of the new cavity into the nest box. To get this swarm out to the house, the beekeeper will need to go the chapter on removing bees from dwellings rather than hiving swarms.

Inside the new nest cavity

The swarm busily goes about setting up bee housekeeping. With no brood to feed comb construction and honey collection goes quickly. Natural swarms do seem to have a maniacal work ethic. Under the same conditions, a natural 3-pound swarm will out-produce a 3-pound package. Neither have brood to feed so I am again guessing that it must have something to do with harder work and innate instinct.

New comb is rapidly built (depending on the size of the swarm and the goodness of the nectar flow) and honey is stored. Upon leaving the parent colony, the swarm members take full honey stomachs of food, but that temporary food source is quickly used up. Fresh food must be gathered. The queen’s food rations are again much improved. She gains weight and expectation of her egg-laying capacity increases – greatly. Much must be done before Winter, which is only a few months away.

More discussion on #3, the Hanging Swarm

If the beekeeper could have arrived on the scene when the swarm had been settled for only a few hours, the bees could have been easily hived with little concern for stings. However, if days pass, the bees will use up the reserves they took along and they become cranky, sometimes very cranky. This “primary” swarm becomes “dry.” Dry swarms are prone to sting more than we like. Misting the dry swarm with sugar water – abundantly – may help improve their attitude before shaking them into your swarm box.

Some descriptive swarm names

A primary swarm may also be called a prime swarm or a hanging swarm. A hungry prime swarm is a dry swarm. Secondary swarms (occasionally called after-swarms) are small swarms that leave after the primary swarm and may or may not be mating swarms. A swarm that is unsuccessful at finding a nest cavity and nests outside is an exposed swarm that becomes an exposed colony.

All swarming is not successful

All swarming is not successful – not for the beekeeper nor for the bees. There are clearly complex rules to swarming behavior, but we, as beekeepers, don’t always know what they are. Give space before the colony needs it and keep young queens at the colony’s helm; otherwise respond to what the colony does during swarming season. It will pass.

Swarming is beekeeping personified

Spring swarming is still a common honey bee event. No matter how old the beekeeper or no matter how long the beekeeper has managed bees, a prime hanging swarm elicits beekeeper excitement. It is one of the benchmarks of keeping bees.

Thank you

I appreciate you reading my ramblings. I truly enjoy working for you.

Dr. James E. Tew

Emeritus Faculty, Entomology

The Ohio State University

tewbee2@gmail.com

Host, Honey Bee

Obscura Podcast

www.honeybeeobscura.com