I’m Listening to What You Tell Me

James E. Tew

You are older today than you were yesterday

Yes, you are one day older today than you were just yesterday; and yes, aging happens to all of us. Not a single one of us is excluded. During November 2021, at seventy-three and one-half years old, I arbitrarily decided that the techniques that I had used to keep my bees for nearly fifty years, were no longer appropriate for me. If your time has not come – it will. Good news! I have not found aging to be horrible, but I have realized that aging requires that I do some things differently – especially in my beekeeping.

As an aside (and other comments in my editorial defense)

I admit that I get bee things on my mind that are reflected in what I write in this monthly column. Many previous obsessive subjects have come and gone. It is, no doubt, obvious to you – if at this moment, you are still reading – that presently I have this smaller colony subject on my mind. I started naively enough. My colonies were consistently growing too large for both my physical stamina and my neighborhood apiary. Plus, these large colonies are really difficult to manage when applying mite treatments. Having no interest in not keeping bees, I opted to explore keeping bees with smaller populations.

I wrote about my findings. Then in subsequent articles, I wrote even more. Then readers began to write me about their single deep experiences. Some of you, I have discovered, have consistently been using single deeps as your primary hive for quite some time. Additionally, while looking at old bee books and old supply catalogs, I realized that small colony hives were abundant years ago. In many ways, this small colony topic is an old concept. It’s just recent to me.

Smaller, lighter bee husbandry

Henceforth, I want to keep my bees (mostly) in single deeps and only deal with smaller populations of bees. Increasing age is not my only reason. My neighborhood is changing resulting in my bees being more scrutinized by people who do not have my interest in beekeeping. Nearly as important in my bee management decision as my ever-increasing age is efficient Varroa mite control techniques. At times, I have had dismal success when trying to control this predaceous mite in large, beautiful, populous colonies. That’s just me. Others of you have done better, but consistently, I have not been able to reduce Varroa populations dependably and efficiently in large colonies with honey supers in place. Hold that thought for just a paragraph or so.

Did you know Bee Culture offers this free feature?

In the recent December (2021) and January (2022) issues of Bee Culture, I’ve written about my personal, late-life beekeeping epiphany. For those readers who really just need something more to do, and you don’t have ready access to my earlier musings, you can find full-text facsimiles at: www.beeculture.com.

Once you are on the home page,

- Go to the upmost back ribbon that is at the top of the page and select, Latest Issues from the various pulldown menus.

- The next screen will open showing the covers of the most recent monthly Bee Culture publications.

- If you are searching for my past articles in December 2021 and January 2022, move your curser to those publication covers. Click on them.

- Tedious and Important point here – just beneath the date shown in the page center, click on “Click here to access the web edition”

- The stored publication will open. Use the directional arrows to find the Table of Contents, then relocate to that page.

- Read as much as you wish. It’s all free.

Okay, back to smaller, lighter bee husbandry continued

I fear that I will finally annoy some of you readers with my thread here. This will not be the first time that I have pushed this smaller colony concept. Many of you are at a place on your beekeeping journey where the largest colony possible suits your program. As I have noted in earlier articles, I do not disagree with your concept of a perfect hive. But for me, those huge populations are not working well for me anymore. Now, I sense that my biggest problem is that I am writing about this concept as I have thoughts on the subject. My article here, as if were, is still warm. But consider the following points.

Beekeeping has been here before

In our beekeeping history, we have certainly been at this single brood nest concept before. This idea is not something new. It only takes reviewing any of the myriad old texts to find photos of single-story concepts in nearly every pictured bee yard.

The characteristics that are different in the current beekeeping world are: (1) Today’s modern queens are truly reproductive marvels. This has not always been the case. (2) Our nectar and pollen sources are only a pittance of what they have been in our beekeeping past. (3) Our environment is replete with pesticides and toxins that seem to restrict our bees’ development. (4) Modern beekeepers must restrict introduced predaceous mite populations and other recently introduced pests that drag our bees down.

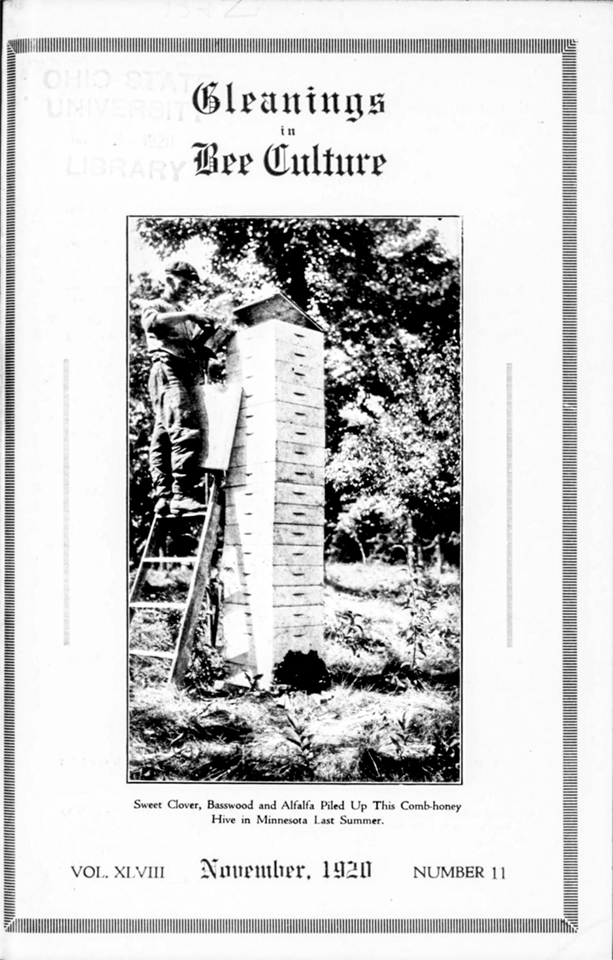

I must guess that primarily due to two to four above, modern beekeepers cannot hope to have the opportunity to snap photographs of those huge honey crops that were possible in the past. In the photo, I present the cover from the November 1920, Gleanings in Bee Culture. Atop a single deep brood nest are fifteen comb honey supers. Other than telling me that the crop was from Minnesota during the summer of 1920, and was from sweet clover, basswood, and alfalfa plants, I know nothing about the colony.

While this photo probably does not reflect the experience of most beekeepers of the day, it seems to have been possible for such crops to occur. I would guess that the photo shows the total number of supers that was produced by that colony within that Spring and Summer of 1920. There simply cannot be enough bees in a single deep to cover that many combs in all those comb honey supers. Plus, the bottom comb honey supers would have been badly travel-stained by all the upward forager traffic. A competent comb honey producer would never have allowed that management error. Even so, producing that much comb honey in one season on one single brood nest colony would be a “breath-taker” today. (Who knows? I suppose there is the unworldly possibility that the nectar flow was so intense that the bees made an unworldly amount of honey in a inconceivability short time. As you know, I was not there.)

Charlie P. from Tennessee, alerted me to this

Charlie and I have talked bees and life on many occasions. He has told me of his Tennessee operation where he has had good luck keeping his colonies in single deep brood bodies. He said, as I have come to understand, that controlling varroa is paramount to productive beekeeping. He can control varroa more efficiently within a single brood box.

On a second note, thank you, Charlie P., for alerting me to an article in an older back issue of Gleanings in Bee Culture. I have no idea how you knew this piece was in the beekeeping literature. My compliments to you.

In the June 1982, issue of this beekeeping magazine, Gary Friedman contributed a piece titled, Single or Double Brood Chambers – A Two-Part Look at A Controversial Subject. Mr. Friedman seemingly made his observations on his colonies when they were in an apiary in Houston, Texas. He consistently wrote that his comments may not be applicable for northern beekeepers. I’m in the upper Midwest, so, there is that fact. Mr. Friedman wrote, “Having large brood nests is a smart idea. But at the same time, using a double brood chamber when the queen is only laying in one of the supers means that we beekeepers are often losing about 80 pounds of good Spring honey. Correct management of the brood chambers is perhaps the most important tool for producing large crops of honey.”

My takeaway from Mr. Friedman’s writings was that, indeed, I have not been actually managing the bees’ brood nest. I just kept giving them abundant hive space to forestall swarming behavior and to build large populations that would ostensibly mean large honey crops. But my management process would inadvertently build large varroa populations if I did not perform multiple mite control programs. As I have written to the point of misery, controlling mites in large colonies in not easy or efficient.

Amy M. from New England alerted me to this

Amy said, I have been keeping bees for 18 years in Betterbee Beemax™ hives. The past three years, I have moved to keeping them in single deeps. (I’m getting older and a full deep of honey in August is just unmanageable for me).

I do not paint the insides, except for the screened bottom boards. I only paint the parts that get exposed to the sun, which is the most important part to maintaining their longevity. I have some boxes that are 16-17 years old. The only ones that I’ve lost were the result of a bear visit.

What I have found, is that some colonies really do want to swarm in the singles, (mostly ones installed on drawn comb), but some don’t. The extra swarmy ones need to be split and managed, or have the queens replaced. I often move those queens and a few frames into a resource nuc. Queens in their second year up here in New England, I will put on a second deep, and once she lays it up, I will take that second deep off and make two splits out of it so I can keep those genetics.

Keeping the single brood chamber in polystyrene is easy. The queen lays out all 10 frames without issue, there is plenty of brood and I am thinking that perhaps they don’t feel so crowded since she’s not dealing with two outer frames on each side being filled with honey due to wooden hives not keeping the temperature so even. (This is purely anecdotal)

Jim, if you’re trying to keep your colony numbers down (which I gather you are from what you have been saying on your podcast Honeybee Obscura), then put on an excluder and just pile up the supers as high as you can (a la University of Guelph) and give an upper entrance. I find I don’t really need to worry about the swarming after June if I give them plenty of space up top. I also add my empty supers directly over the brood chamber instead of on top of the filled supers, I don’t know if it makes a difference or not in terms of them thinking there is more space.

I have been focused the past two years on sustainable queen rearing. Making my own queens. They are just too expensive now and as you know acceptance is not guaranteed. So, having those resource nucs or making those splits are vital to my operation. If I somehow end up with too many, then I can easily just give them away by sending an email to my local club. Someone always needs a queen, so having those extra nucs doesn’t necessarily mean I’m growing my apiary.

Strips for varroa control are easy in a single to add and remove, especially outside of honey super season. I never have to remove that top deep of cranky bees in the Fall to dig out whatever treatment I’ve put in.

For now…

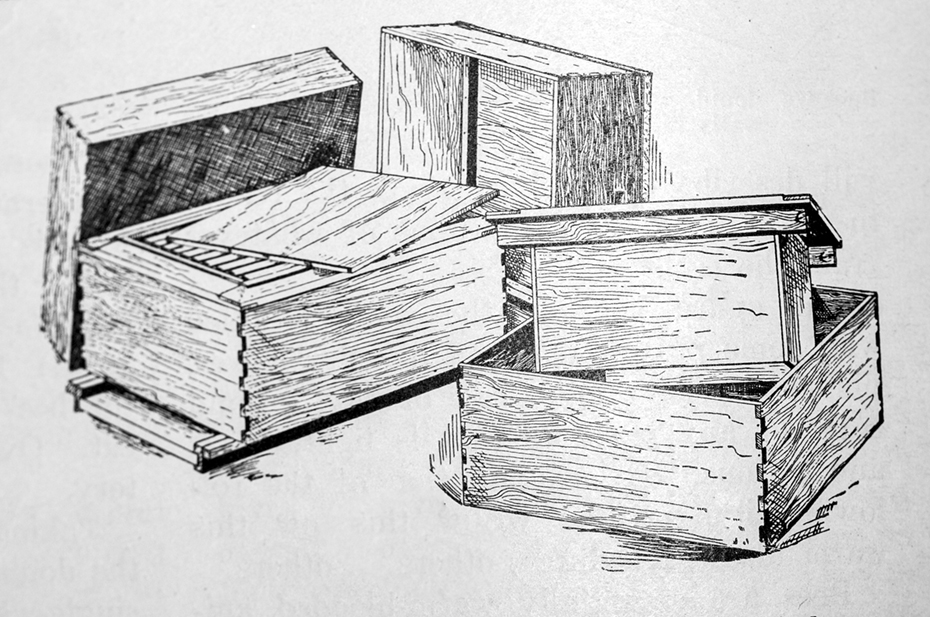

Okay reader, now you’re back to Jim. I’m out of space, but I am far from finished. Far. But for now, a closing thought. Do those of you who are deeply established within beekeeping history recall the Buckeye Hive design manufactured by the A.I. Root Company during the 1920s and 1930s? During those years and into the war years, beekeepers were very serious about wintering honey bees. To a great extent, we have gotten away from that seasonal management dedication today. Before Varroa, it was just too easy to get more replacement bees rather than worrying about wintering losses. I am reconsidering this management drift in my apiary.

The Buckeye Hive was an insulated single-story unit with an oversized outer cover to allow for an insulating quilt to be positioned inside. This old hive design strongly resembled the expanded polystyrene hives of today. I would contend that beekeeping has nearly come full circle. The plastic foam hives of today are essentially the Buckeye Hives of the 1920s.

Varroa has called me out

Okay, I need to admit – at least to myself – that varroa not only has played a significant role in how many colonies I can now manage. I am realizing that – for me – to restrict Varroa populations within my colonies, I need to manage the bees’ brood nest mechanics more than I have been in decades past. Seemingly Varroa has dictated how many colonies I keep, and now, Varroa is dictating the size of the brood nest in those colonies.

My beekeeping destiny appears to be fewer colonies with more manageable brood nests and an increased concern about wintering assistance. What others have already accepted for years, I am now fully embracing. That varroa predation and wintering success are intimately associated is a clear relationship. It’s true. I am managing both honey bees and Varroa mites.

Charlie P. and Amy M., thank you for essentially writing this article. I freely acknowledge your input. No doubt the readers will appreciate your experiences.

My video for this article

For most monthly articles, I produce a short video that supports the concepts that I addressed in the article being discussed. This month, more than most, I have used that video medium to review what I have been trying to write in recent three articles on this small brood nest subject. I hope you will have a look. I have enjoyed exploring the concept of single box colony management.

Dr. James E. Tew

Emeritus Faculty, Entomology

The Ohio State University and

tewbee2@gmail.com

http://www.onetew.com

Weekly podcast at: www.honeybeeobscura.com

https://youtu.be/MTRi_LNi6bQ