Click Here if you listened. We’d love to know what you think. There is even a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

Found in Translation

What’s in Your Bee Scene?

By: Jay Evans, USDA Beltsville Bee Lab

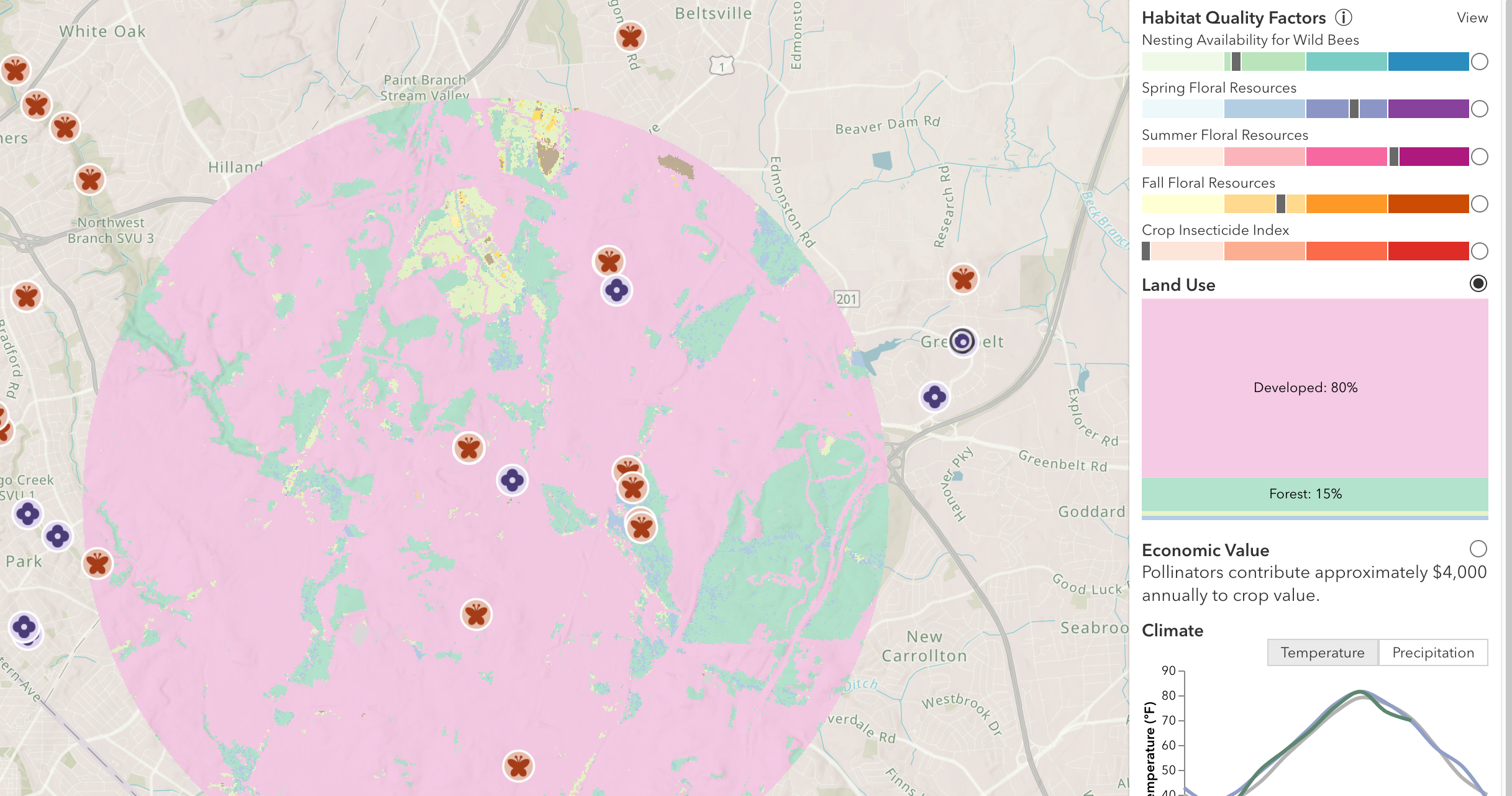

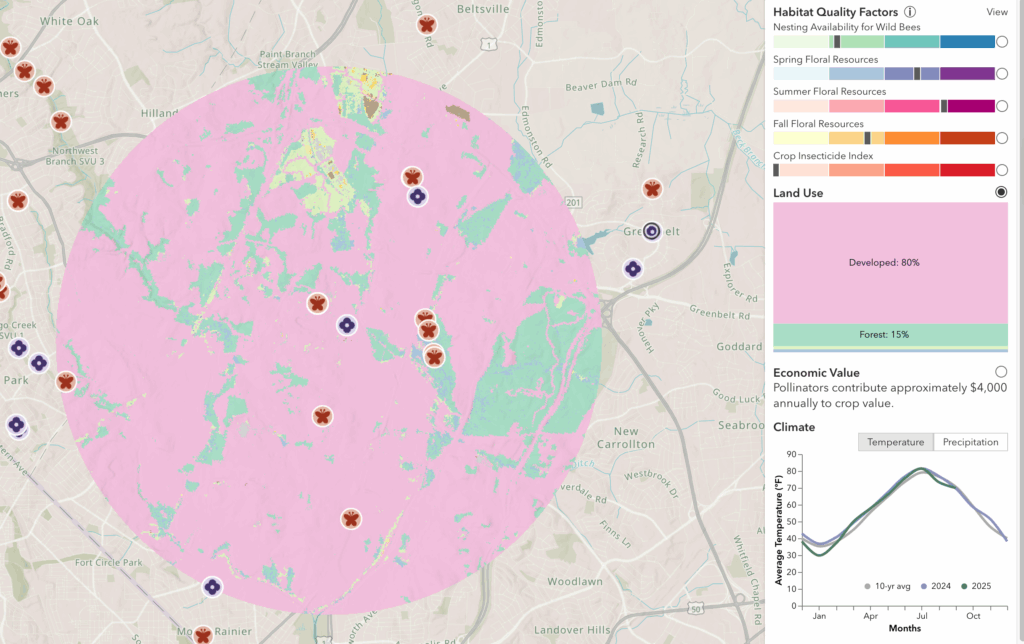

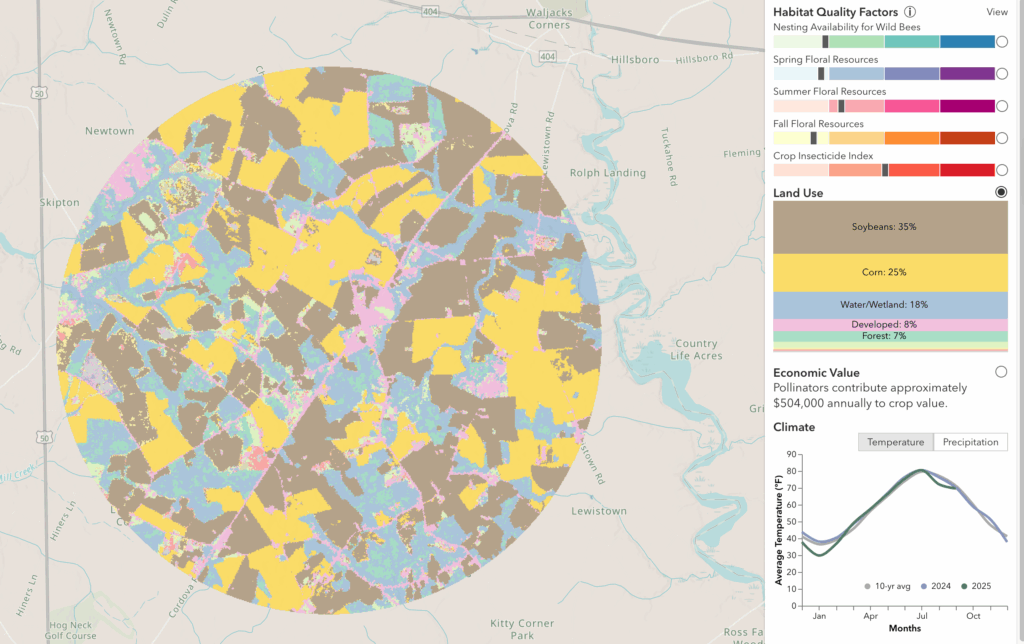

Whether you consider your honey bees as an agricultural asset or something more like a pet, bees defy both of those categories in the way they collect the food they need. Specifically, bees travel far outside of your property lines in search of food, reducing the control a beekeeper has over what they eat and when. Among livestock, maybe open-range cattle and sheep come close to that, but even these are rounded up into smaller pastures or stockyards most of their lives. In most neighborhoods, you will get in serious trouble for keeping free-range livestock (try keeping goats and eventually you will receive pushback from neighbors irked by grazing beyond your property lines). Similarly, free-foraging pets are largely a thing of the past. Plants, of course, live on whatever you give them in their local terroir. Bees, by contrast, are roamers and opportunists, flying 2-3 miles and ambivalent to property boundaries. As a beekeeper, it serves you to know what those other properties are made of. If you are a certain type of beekeeper, you will even place your bees at an inconvenient distance from your own home in order to give them a better environment. So, what are the best sources of information, other than a cash pollination contract, to use in deciding where and when to set up an apiary? I have mentioned the Beescape effort developed at Pennsylvania State University before, and its ambitious attempt to give beekeepers a free tool to assess the quality of forage around their current or planned apiaries (https:// Beescape.psu.edu/). Since now is a great time to picture where your bees might be placed in the Spring, it seems worthwhile to review the state of Beescape and insights into what makes for good hive placement in the U.S. Beescape compiles publicly funded databases for habitat use, pesticide application, and climate, letting beekeepers see how their 2- or 3-mile circle of foraging looks from the standpoint of hungry bees. It can also help you envision neighboring sites that might be more enticing than your back yard.

Like many applied science projects, Beescape is continually improving. I was impressed with how it labeled two areas I am familiar with in the context of bee habitat; my own inner-suburb town (lots of pink for ‘developed’) and the more agricultural eastern shore of Maryland (less pink, and more fields of corn and soybeans). It gets more interesting when one looks at the types of forage and possible risks. My forested and urban area actually provides a decent and low-pesticide landscape for bees. The lower density eastern shore has a higher pesticide risk level, and some land use that is equivalent to paved acreage from the standpoint of a hungry bee. If you have choices for beekeeping spots, perhaps at the level of a county, you can almost certainly find spots that differ in land use in ways that will affect the health and productivity of your bees. So what do actual beekeepers think of this resource? The developers of Beescape admit that initial opinions by beekeepers were mixed; they did not really love the wonkiness of some of the land-use labels, and/or felt the site navigation was awkward. So, the team put much work into improving both the interface and the underlying data of Beescape. Recently, they formally queried a set of beekeepers to see how BeescapeNexgen is serving them. In a paper led by Lily Houtman (Houtman, L., A. C. Robinson, D. McLaughlin, and C. M. Grozinger. 2025. Evaluating the usability and utility of a spatial decision support system for pollinator ecology. Ecological Informatics 89:103182, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2025.103182), these researchers invited 43 beekeepers to conduct defined explorations on Beescape. These beekeepers reflected the U.S. beekeeping world pretty well (modal age of 55-65, my peeps!) and ranged from having little experience to 46 years in the trade. They seemed to share my enthusiasm for the outputs and insights, citing the landscape and forage insights prominently. The vast majority of surveyed beekeepers said they found utility in the habitat, map, and forage outputs, and 90% said they felt confident they could interpret the results without additional guidance, pretty amazing for a science-based dataset. It doesn’t seem like many of the surveyed beekeepers were commercial pollinators since they found the details on how their bees might aid local crops somewhat less interesting (not to say that beekeepers aren’t proud that their foragers are putting food on someone else’s table). The only category that scored poorly (14% ‘mostly agree’) was “Beescape would help me meet local beekeepers”… hey, it’s not a dating app, join your county club! The reviews are strong vindication that the years put into this resource by the Beescape team have been well worth it. The resource also points to the value of land-use data collected over many decades by federal and state agencies.

I don’t pretend to know how various landmarks and maps were integrated for this resource, but if you have a true passion for this, and some math skills, you would enjoy a recent chapter in the ‘Beebook’ compilation of protocols and references for honey bee science. Beebook is a volunteer effort put on by the international Colony Loss network COLOSS (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0005772X.2021.1981677) aimed at saving time and resources by publishing cookbooks of scientific methods. This particular recipe, led by Stephanie Rogers (Rogers, S. R., B. G. Foust, and J. R. Nelson. 2025. Standard use of Geographic Information System (GIS) techniques in honey bee research 2.0. Journal of Apicultural Research 64:443-532. https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2024.2357977) covers a widely used tool for placing features on electronic maps, a tool used by everyone from turtle conservationists to oil prospectors. Geographic Information Systems were launched by Canadian geographer Roger Tomlinson in the 1960’s, eventually becoming a resource not just for government super-computers but for cell phones and laptops. This 91(!)-page review covers GIS as applied to knowing the rewards and hazard bees might face in their foraging world.

And if you want to take a more active role in shaping your own Beescape, there is an abundance of recent work describing the benefits of changes in land management for pollinators. One recent study invoked Beescape and additional mapping resources to predict how modest changes in local land use will affect honey bees and other pollinators. Dean Pearson and colleagues (Pearson, D.E., DePuy, A.L. & Kuhlman, M.P. 2025. Inspiring citizens and municipalities to initiate pollinator conservation: the urban pollinator matrix modeling tool. Urban Ecosystems 28, 91, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-025-01703-9) used beautiful Missoula, Montana, as a template for subtle tweaks in land use at the neighborhood level. Converting grass lawns to other green uses had the predicted positive effect on pollinator levels, with the easiest step being so called ‘pollinator lawns’. Pollinator lawns are what your homeowners association might call ‘neglect’, whereby passively ceasing mowing encourages a succession of dandelions, clovers and other plants that can start to get an edge on turf when they are not constantly cut down. These pollinator lawns served honey bees well. One of the reasons we love honey bees is their ability to scrape pollen and slurp nectar from almost any flowering plant, and honey bees were predicted to fare better with almost any form of flowers arising from lawns. Other bees are more specialized to diverse native plants, and their numbers are predicted to respond when land managers culture or favor more diverse native plants (these also benefit honey bees, of course). As someone who has actively supported local garden centers, and lost a considerable fraction of purchased pollinator-friendly plants to deer and rabbits, I realize that building an ideal pollinator habitat is not easy financially or timewise. This paper gives a pragmatic view, showing what even minimal shaping of lawns by land managers can do to help bees. You might have to be resilient to eye rolls from dogwalking neighbors if you relax your mowing habit, but science and bees are on your side. If nothing else, please read the beekeeper review of Beescape, try it out yourselves, and give the developers of this fine resource feedback as it continues to develop as a free and helpful tool for both beekeepers and those who are simply curious about their local environment.