Click Here if you listened. We’d love to know what you think. There is even a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

Richard Wahl began learning beekeeping the hard way starting in 2010 with no mentor or club association and a swarm catch. He is now a self-sustainable hobby beekeeper since 2018, writing articles, giving lectures and teaching beginning honey bee husbandry and hive management.

Off the Wahl Beekeeping

New(ish) Beekeeper Column

Reflections on the Past Season

By: Richard Wahl

I Question the Original Article Title

When I first considered writing an article about the unexpected events that arise in the early years of beekeeping, I thought of naming it “Surprises in the Bee Yard”. While fitting, that title seemed too narrow as it suggested a simple list of events without exploring how they shaped my beekeeping practices and understanding. As a fourth year beekeeping mentor, along with four to five other experienced beekeeping instructors, we are reminded as the class progresses that we often ask students while inspecting hives, “What do you see?” or “What are you looking at?” This first evaluation step is not worth much if there are no follow-up questions like, “What is this telling you to do?” and/or “What do you plan to do about the observed information you have gained?” This is much the same as listing surprises without subsequent actions to be taken. Reflecting on past events should lead to logical adjustments to our beekeeping regimen to improve the likelihood of long term sustainability. Little progress is made if all we look at are the current events in our beekeeping efforts, continuing to do the same things without making adjustments and changes to the most recently observed events. Beekeeping is an ever evolving adventure and we as beekeepers need to evolve new strategies to keep up with this continuously changing evolutionary process.

The Value of Experience

As with most new endeavors starting in beekeeping has a myriad of new experiences and expectations. I was as naïve in my first year as anyone assuming my swarm catch box of bees could be left to their own devices and in the Fall I would possibly be able to collect some honey. Little did I realize when I began that there would be a lot more to managing bees than just monitoring the box that they live in that we call a super. The concept of feral bees fending for themselves in hollow woodland trees seems to permeate the beginner’s concept of beekeeping. It only takes the loss of a hive or two over those first Winters to galvanize the need for more constant vigilance in mite management, Winterization techniques and seasonal feeding regimens. And of course, swarm catches, Spring split benefits and nucleus colony (nucs) usage will also come into play for the sustainable beekeeper.

I have found that taking notes on hive performance and conditions each time I visit my apiary has helped me improve my beekeeping operations to the point where sustainability is the norm rather than a dream for the future. I’ve lost count of how often I’ve run into something new or reviewed old notes to remember how I solved a similar problem in the years before. During my first year of research in beekeeping I kept coming across the fact that maintaining two or three hives was a much better option than only having one hive. From my second year on I never kept less than two hives in operation during a season. The value of having more than one hive became clear when I helped a first-year beekeeper a few years after my beginning. The individual noted that one hive was thriving, while the other seemed very less active and unproductive. I made the short trip to assist in a hive inspection and found one first year hive doing very well while the other had a much smaller population; no eggs, no young brood, no obvious queen or queen cells and a few misplaced medium frames in a second story deep super. The misplaced frames were easy to adjust to deep frames, although one medium frame with drone comb drawn below to the depth of a deep frame, was left in the hive.

The drone comb drawn out just below the medium bottom with larvae were beginning to be capped, meaning there were twelve to thirteen days before uncapped drone would emerge. Removing that frame a day or two before drone emergence would also remove any mites that had moved into the capped cells. It is typical for bees to draw out drone comb hanging below a medium frame between the other deep frames. Some beekeepers use this technique rather than the green drone frames meant for the same purpose. We then moved a deep frame with eggs and small larva from the strong hive into the weak one. It was reported later that Fall that the weak hive had produced a new queen and both hives were doing well. If this first year beekeeper only had the weak hive they may not have realized they had a problem as soon as they did and may not have been able to save a single problematic hive later in the year.

Planning Ahead

Like most new beekeepers, I had a hard time foreseeing needs down the road. In my early years, I always seemed to be playing catch-up. Mite testing and treatments were consistently one step ahead of my actions. I am fairly certain I lost several hives over early beekeeping Winters because I tried to stay as chemical free as possible; and in doing so, acted too little, too late. Since then I have learned that timely monitoring and treatment, when necessary, is actually the better path to reducing chemical use. Trying to play catch-up with mites is like trying to put on a seatbelt after the crash.

Swarming was another blind spot for me. As a new beekeeper, I did not fully appreciate how inevitable swarming can be, especially from strong overwintered hives. Extra space alone does not always cut it. It is far better to take early action and have your equipment ready than to watch half your hive fly off. Watching swarms leaving my hives on three different occasions through my beekeeping career reinforced this. Brood breaks, moving queens to splits and careful monitoring of adequate, but not overly great new hive space, seems to have decreased swarms emanating from my hives.

Another surprise was how often I would need more frames and supers. When I get new frames, I like to add a coat of my own beeswax to the foundation. Bees seem to draw out comb just a bit quicker when this is done. Planning ahead to have enough refined bees wax on hand to melt for this purpose became another challenge. When I began selling five frame starter nucs it did not immediately occur to me that with every nuc sold five frames disappeared. I now make sure to order extra frames and foundation to assemble over the Winter, so I am not scrambling during nuc season.

And do not forget the unpredictable nature of swarm catching. Every swarm is a gamble, and I hate to pass up on free bees. Large swarms caught early in the season usually yield a honey super or more for my taking, near the end of honey harvest season, without degrading the capability of the swarm hive to adequately overwinter. In the end, it all comes down to planning and resisting that bedeviling urge of procrastination. We have all fallen victim to procrastination, promising to act tomorrow. But in beekeeping, procrastination tends to bring mites, swarms, and frame shortages right to our doorsteps.

2. Some completed frames in a frame construction jig while others wait to be assembled prior to plasticell insertion.

Photo credit: Richard Wahl

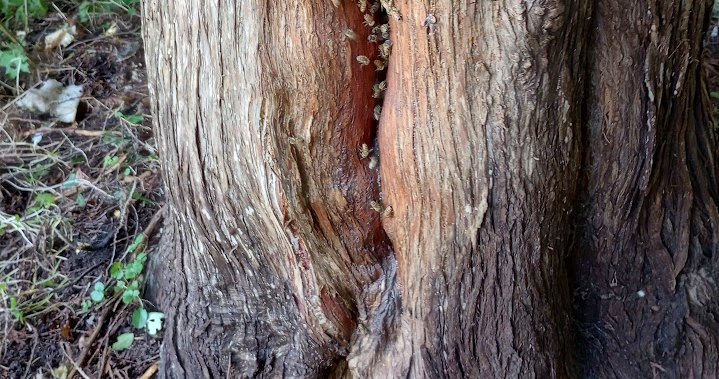

Expect the Unexpected

No matter how many books you read, classes you take, or mentors you shadow, nothing truly prepares you for the constant surprises that beekeeping throws your way. The bees don’t read the manuals and neither do the pests, the weather, or the equipment failures that seem to happen at the worst possible time. In my early years, I found myself regularly standing in front of a hive, scratching my head, wondering, what now. Why are there no eggs or brood when I just marked what appeared to be a strong queen a few weeks ago? It might just be that the hive swarmed and the new queen has not yet completed mating flights and begun to lay eggs. The explosion of bees emerging from cells can be very misleading shortly after a swarm event. Although I could swear a hive had not swarmed in my beginning years that opinion changed after witnessing swarms leaving a hive and then doing a quick inspection. The remaining bee population seemed to be strong and as a novice beekeeper, had I not witnessed the swarm I would have been none the wiser.

On another occasion I came back to a hive that just seemed to disappear. It had evidently absconded for no apparent reason that I could immediately ascertain. Upon a more thorough inspection the hive only had very old comb I had meant to replace. But as the Summer wore on I ran out of equipment to increase the hive space and used my only remaining oldest drawn comb. The bees may have taken an affront to this and decided to leave.

In another Summer, well into my beekeeping years after many with never seeing a hive beetle, I suddenly had hive beetles in several hives. I initially assumed the first ones may have flown in from some other area apiary, which they are known to do. Later I realized another possibility. I had sold several nucs at economic prices because the purchaser decided to give me replacement drawn comb frames. Placing those replacement frames directly into hives may have introduced hive beetle eggs. From that point on I have always placed any previously used frames in a freezer for a day or two to kill off wax moth or hive beetle larva and eggs if frames have had extended storage with no use.

I think an entire book could be written about queens and queen anomalies. I recently captured a swarm as a result of a phone call from a honey patron. After dropping the swarm in a hive from a low branch, I then closed and collected the hive later in the evening. Carrying the ten frame supered swarm thirty yards to my pickup and then when home for another twenty yards to my apiary, I could hear the frames shifting inside the super. The next morn a walk past the new hive revealed a worker dragging a nice, but dead queen out of the hive. I was immediately concerned about the rattling frames possibly killing the queen during the moves. But having learned patience with previous swarm encounters I gave the hive a week or so before its first frame by frame inspection. At that first inspection I found nearly all frames with newly drawn comb, plenty of eggs and small larvae and I even caught the mature queen which I then marked. Evidently the swarm had left with at least one other virgin queen, who had lost the battle for hive supremacy and I had the luck of watching her being discharged from the hive the next morning. I may not have been so patient had I not witnessed different queen results in swarm catches in previous years. Two swarms on the same day resulted in eggs spotted in comb within a few days. Several days later two more swarms of about the same size, most likely after-swarms all from my hives, slightly concerned me at the time as more than two weeks went by without any evidence of a queen’s presence. Turns out the second set of swarms surely had virgin queens that needed time to go out and mate before any eggs were laid which they both did after the short eggless sabbatical.

On another occasion, this past Summer, I have simply not been able to locate a queen in a nuc. Of fourteen nucs, half were given a queen from an overwintered hive allowing the parent hive to produce a new queen. The remaining nucs were allowed to produce a new queen which I found and marked in all but one. As that last nuc grew from five frames to ten to fifteen I always found day old eggs insuring a queen was present. I normally do not do frame by frame inspections more than once or twice in a season. However, after seven repeated frame by frame inspections, always spotting day old eggs, I have yet to find the illusive queen in that last nuc which is growing as it should.

One of the most valuable traits a beekeeper can develop is adaptability. Your bees are constantly adjusting to their environment, be it weather, forage, predators or diseases and we have to do the same. I have learned not to panic when things go off-script, because they always will. Hives not producing honey, queens not laying, or wind storms blowing hives over; there is always something unexpected around the next corner. The trick is not just to expect the unexpected, but to prepare for it. Keep spare equipment on hand, read your bees closely, and never assume that a problem solved once is solved for good. Beekeeping has a funny way of humbling us right when we think we’ve got it all figured out.

4. A strong hive with a yet to be marked queen not found after numerous searches.

Photo credit: Richard Wahl

Summary

In the end, surprises in the bee yard aren’t just inconveniences, they are learning opportunities. Confusion often becomes clarity, if we take the time to reflect and adapt. The longer I keep bees, the more I understand that this isn’t a hobby of perfection, it’s a craft of constant adjustment. Experience may not prevent surprises, but it does teach us how to respond with confidence. And perhaps that’s the best preparation we can hope for. Not to eliminate uncertainty, but learning to work with it.