Click Here if you listened. We’d love to know what you think. There is even a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

Found in Translation

Drone Patrol

By: Jay Evans, USDA Beltsville Bee Lab

The renowned Australian bee scientist (and co-manager of Australia’s National Honey Bee Genetic Improvement Program), Elizabeth Frost, sent this magazine an interesting observation about drone bees, which was swiftly passed along to smarter souls. I realized my knowledge of activity at honey bee mating hotspots was a decade or two out of date and needed a rebuild. Luckily, there have been some great advances in the past year or so in the art of confirming likely Drone Congregation Areas (DCAs), identifying most likely hookup times, and vetting the participants. A lot of this comes from on-the-ground patience (i.e., hours of watching queen departures and returns from mating boxes while having your friends try to track drone flights from busier full colonies). However, amidst all this, new technologies are emerging to reduce the human workload and provide more accurate data. These technologies are being deployed both at ground level and high above us.

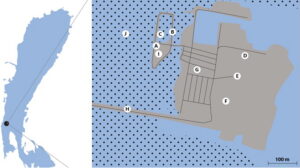

“Overview of Lake Neusiedl with position of the island and locations of drone colonies (A), mating boxes (B) and sites where DCAs were surveyed. From Sprenger et al., 2025 (Creative Commons license 4.0) Blue: water, dots: reeds grey: island”.

For the former, Aleksandar Uzunov and colleagues in Macedonia and Germany described a reasonably inexpensive mating box that can be outfitted to increase the chances of catching queens as they leave for and return from flights (Uzunov, A., Andonov, S., Dahle, B., Kovačić, M., Prešern, J., Aleksovski, G.,…Büchler, R. 2023. Standard methods for direct observation of honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) nuptial flights. Journal of Apicultural Research, 63(1), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2023.2251201). A key change to the standard-issue structure was to add a queen excluder to ensure chastity until the time was right. Virgin queens were installed behind this excluder until the sixth day of adulthood, then were allowed to fly. This setup was used to record the start times of flights, returns, presence of a mating sign, and flight numbers. The authors claim that one agile observer can track 12 adjacent mating boxes in real time with this simple system. As a step up in technology, radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags and readers at the doorway improved data collection by more accurately indicating when the queen was heading in and out. High-resolution video of the hive porches also helped reduce the fieldwork…and video and RFID worked great together. Specifically, RFID could be used to time-stamp long videos with likely queen arrivals, allowing those videos to be scrutinized for queen behavior and signs of mating.

Two additional recent studies used genetics to determine the results of queen forays, with a particular focus on the predictability of drone populations at DCAs. First, Melanie Parejo and colleagues used mating boxes to establish and monitor virgin queens in an isolated mating yard (Parejo, M., Galartza, E., Momeni, J., Gorrochategui-Ortega, J., Farajzadeh, L., Wegener, J., … Estonba, A. 2025. A SNP-based honey bee paternity assignment test for evaluating the effectiveness of mating stations and its application to the Ataun valley, Basque Country, Spain. Journal of Apicultural Research, 64(4), 1172–1181. https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2025.2483540). Their goal was to let queens do their thing, then screen resulting worker offspring to infer the home colonies of successful dads. This worked thanks to a ‘chip’ that determines variants at more than 6,000 points along the bee genome, providing enough data to identify true fathers with greater than 97% accuracy. The technique offered great insights into the mating dynamics of the area. Most interesting to me was that, while colonies from the apiary closest to the inferred DCA provided most of the “in-air” drones (79%), actual matings were tilted toward an apiary nearly two miles away. The authors guessed there was another DCA further away and that queens were doing extra effort to preferentially mate there. This study, coupled with a queen watch at the doors of the mating boxes, would perhaps confirm that queens searching for distant mates spent much longer on the wing. On a practical side, colonies in which the scientists had added drone comb indeed seemed to be more heavily represented as sources of successful dads.

Image of Quadcopter drone, from Project Kei, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Keita.Honda, Creative Commons license 4.0

Thomas Sprenger and colleagues in Austria used a classic trick of bee pigmentation to determine the integrity of a potential island mating system in a recent paper (Sprenger, T. E., C. Menschhorn, and R. Brodschneider. 2025. Investigating mating reliability and drone congregation areas on an island in Lake Neusiedl (Austria) for the potential establishment of a mating station for honey bee breeding. Arch. Anim. Breed. 68:507-516). And they truly HAD an island at their disposal, the striking Mörbischer in Lake Neusiedl, Austria. When not used by scientists to track bee sex, this island hosts a large concert venue and ‘open air’ opera house (https://www.burgenland.info/en/erleben/kultur/kulturfestivals/seefestspiele-moerbisch). It is connected to the mainland by a 1.2 mile causeway, but is thought to be resistant to outside and resident drones. Unlike queens and workers, drones are extremely hesitant to fly over open water. After painstakingly establishing pure Cordovan (leather-colored) virgin queens in mating boxes and an array of 11 drone-producing colonies also headed by pure Cordovan queens, all the researchers had to do was wait and check the color of the worker offspring. Using balloons and Quadrocopter ‘drones’ they found no males flying before drone producers were introduced to the island, and healthy DCAs after those colonies were present. All good for an isolated mating yard. Nevertheless, worker progeny from ten mated queens indicated a significant number of outside males had crashed the mating party. These events could reflect adventurous males from the mainland, but the authors feel it was far more likely that virgin queens had decided to fly some miles to meet up with off-island males. Only one of these successful queens had mated exclusively with cordovan ‘island’ males. Eight queens mated with some local males while also having at least one mainland fling. The tenth queen spent all of her time with mainland males. Sadly, despite adequate local males, the temptations on this island were not sufficient to keep mating local. For mating yards on the mainland, these two studies suggest that, while ‘flooding’ an area with desired drones can help, queens will readily explore DCAs miles away from home. There is reasonable speculation that this tendency for long, risky, flights to find DCAs is a hedge against inbreeding. Choosing diverse dads for their thousands of unborn children is a key decision point for queens, arguably worth some extra flight miles.