David MacFawn

How much and when honey-processing equipment should be purchased are things to consider for new and developing honey operations. Decisions are based on the operation’s labor rate, the equipment’s cost, and honey yield per colony. The higher the labor rate and the lower the equipment’s cost, the sooner an investment in honey-processing equipment should be evaluated. Most operations currently guess at when and how much they should invest in honey-processing equipment. Also, a lot of new beekeepers believe that they need to invest in honey-processing equipment upfront.

For beekeepers with under eight to 10 colonies, it is recommended they use either a bee club extractor or get someone with an approved honey facility to extract their honey. This is especially true for new beekeepers who are still learning and deciding if beekeeping is for them. Honey-processing equipment is expensive. If a club extractor or getting someone to extract the honey is not available, then the purchase of some honey-processing equipment is necessary.

If your operation is from 10 to about 40 colonies, an extractor, an uncapping tank, and a bottling bucket are recommended. That is about $1,200 to $1,500 in equipment. If good-quality equipment is purchased initially, it will last a lifetime as long as it is well maintained. A clean and well-maintained extracting building/location is required. Clean hot water to clean the equipment, covered lights, a floor drain, a restroom in close proximity is all important.

Honey is hydroscopic and will absorb moisture. For quality honey that will not spoil, the USDA requires the honey to have 18.6% moisture or less. Buckets (five gallon/60 pounds food grade) with lids are needed to store the honey. A filter is also needed to remove any extraneous wax, bee parts, etc., from the honey. This filter is typically placed on top of the honey storage bucket when the honey drains out of the extractor into the storage bucket. A 60-pound bucket with a honey gate will work for bottling small (200 to 500 pounds) amounts of honey. If you expand to more than 40 colonies and therefore produce more honey, a more expensive honey-bottling tank with a dripless honey gate is in order. A capping’s scratcher and uncapping knife are also needed. The scratcher is for uncapping the cells that the uncapping knife misses. The scratcher should be used as little as possible to avoid minute wax particles from getting into the honey. Wax particles result in honey cloudiness and premature granulation. The cappings can be left to drain in the uncapping tank for small amounts of honey extracted, or moved to another bucket, with a honey grate, to drain.

When you start producing more than 1,500 to 2,000 pounds of honey, a more elaborate setup may be used. An uncapper and possibly a capping’s spinner is in order, with a water-jacket bottling tank. An uncapper will speed up your honey extracting immensely. A water-jacket bottling tank will ensure your honey does not get too hot. Overheating honey degrades the flavor and nutritional benefits are lost. The honey-processing equipment purchase and expense can be spread out over several years (depreciated). An operation’s honey extracting through-put can be sped-up by using two extractors. One extractor is spinning/extracting while the other extractor is being loaded with uncapped frames. This is the computer double buffer memory concept. So, there is a trade-off in cost between extracting speed/labor cost and equipment cost. If the honey-processing equipment is going to be used for years, then it pays to invest in two extractors. Investing in motorized extractors is recommended. Motorized extractors are easier to use and will speed-up the extracting operation.

Equipment Cost Entries. The reader is referred to: http://www.maxantindustries.com/

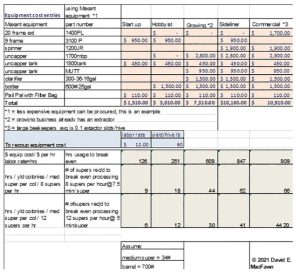

The spreadsheet starts with five different possible scenarios (Start up, Hobbyist, Growing, Sideliner, Commercial) depending on where the beekeeper is at in their company’s development. When starting, you only need an extractor, uncapping tank, and filter. As you increase your operation, more equipment can be added.

In the spreadsheet analysis, the total equipment cost is determined. The hours’ usage to break even is determined by taking the total equipment cost in dollars and dividing by the labor rate in $/hours. The hours’ usage to break even is then divided by the yield per colony divided by the amount of honey per medium super times the number of supers extracted per hour which gives you yielding supers for equipment break-even. Various equipment configuration costs can be examined with the number of supers extracted per hour being varied based on if you have two extractors (one extractor extracting while the other extractor is being loaded) and an uncapper. A mechanical uncapper will speed up the uncapping process immensely.

Financing honey-processing equipment may be an issue. If the operation does not have the cash on hand, consider a loan, depending on the interest rate and amount. An amount of $7,000 to $10,000 may be in order depending on the revenue the operation has. The bank will determine the operation’s debt to equity ratios and other ratios. The operation may have to purchase the equipment incrementally. After the extractor, a bottler and uncapper are the most critical pieces of equipment. Also, purchasing used equipment is an option that may be in order if you can find it. A big issue is having a honey-processing building or location to process the honey. Often a garage or other building/facility can be converted to a honey-processing building. The financial numbers need to be analyzed to determine what the operation can afford. Analyzing the financial numbers is critically important.

When analyzing the financial numbers, the risks need to be evaluated honestly. Things such as how well the operation is at keeping its bees alive and their honey yield maximized are critical. Transportation, feed, medication, and labor costs must be considered. These costs should be analyzed in relation to one another, not independently. Changing one cost may impact another variable/cost. The operation should typically start small and close to home before expanding. With bees, you need to understand the business very well to be successful. This takes practice, education, and communication with experienced beekeepers in addition to book learning.

Usually, for local honey, there are no issues moving and selling the product. Word-of-mouth sales and selling at the local farmers’ market work well. You need to decide what type of jar and label you will use. The jar and label will be determined by your venue and customer base. You also need to determine if you will use plastic or glass jars.

To be successful with a honey operation, the personnel need experience and book learning. Going with the bee biology, instincts, and characteristics are critical for success. You need to go with the bees’ instincts and not against them. The operation should not expand exponentially but should expand incrementally. If under eight to ten colonies, the operation should consider paying someone else or using bee club equipment to extract their honey. As the operation grows, more honey-processing equipment can be added.

David MacFawn (dmacfawn@aol.com) is an Eastern Apiculture Society Master Beekeeper and a North Carolina Master Craftsman beekeeper living in the Columbia, South Carolina, area. He is the author of three books, Applied Beekeeping in the United States by David MacFawn, published by Outskirts Press https://outskirtspress.com/